Introduction

Kinship relationships, networks, and the bonds are probably the most important traditional foundation for social relationship among Zambians and Africans. Kinship are all those important fundamental social connections that happen immediately when any Zambian or African is born. It is the connections that instantly happen when 2 individuals, a man and woman, get married. The kinship relationships happen because of marriage or birth. In traditional Zambian/African societies, marriage was never just the young individual man woman getting married because they are in love; but it was more important that the marriage was the uniting of the man and woman’s families. This article will describe the traditional Zambian/African kinship relationships using Tumbuka terms as examples. The second discussion is the importance or significance of kinship in traditional society. Last, the article will discuss how these kinship bonds are still important today.

Kinship Relationships and Terms

As soon as you are born in a Zambian/African family, of course you will have amama (mother) and adada (father). All your siblings are dumbu or adumbu; which means sibling of the opposite sex; akulu or anung’una; older or younger sisters or brothers. The term adumbu is used for your sibling of the opposite sex with gender distinction embedded in the situational conversation.

All your Father’s Brothers are your adada or your fathers. All your Father’s Sisters are ankhazi or aunts. All your Mother’s Brothers are your asimbweni or uncles. All your Mother’s Sisters are your amama or Mothers. All your Father’s Brother’s children are adumbu or your sisters or brothers if the sibling is opposite gender to you.. All your Father’s Brothers’ sisters children are your vyala or cousins. Your Mother’s Sisters’ children are your vyala or cousins. Your Mother’s Brothers’ children are your vyala or cousins who you joke with and may even be encouraged to marry.

All your Father’s and Mother’s parents are agogo or grandfathers and grandmothers. All your Grandfathers’ and Grandmothers’ sisters and brothers are your agogo or grandfathers and grandmothers.

If you are a man or groom, when you get married, all your wife’s siblings and the people she calls adumbu or her brothers and akulu or anung’una; older or younger sisters are your mulamu or sister-in-laws or brother-in-laws. You become mkweni or son-in-law to her parents and all the people she calls amama and adada or mother and father in her kinship group.

If you are a woman or bridegroom, when you get married, all your husband’s siblings and all the people he calls adumbu or his sisters and akulu or anung’una; older or younger brothers are your mulamu or sister-in-laws or brother-in-laws. You become mkamwana or daughter-in-law to his parents and all the people he calls amama and adada or mother and father in his entire kinship group. The parents of the groom and bridegroom are asebele to each other. All of the above describe kinship relationships that have to do with both your mother and father’s or parents’ generations.

These next kinship relationships describe your own generation. All your akulu (younger) and mnung’una or older or younger’s Brothers’ Children are your sons and daughters. All your adumbu or sister’s or brother’s children are baphwa nephews or nieces.

These kinship relationships are difficult to sort out when one is required to describe kinship relationships between two families; those of the groom and bridegroom. These relationships become more complex when families have polygamous marriages involving large extended families may be involving a hundred men, women, and children.

Significance of the Kinship

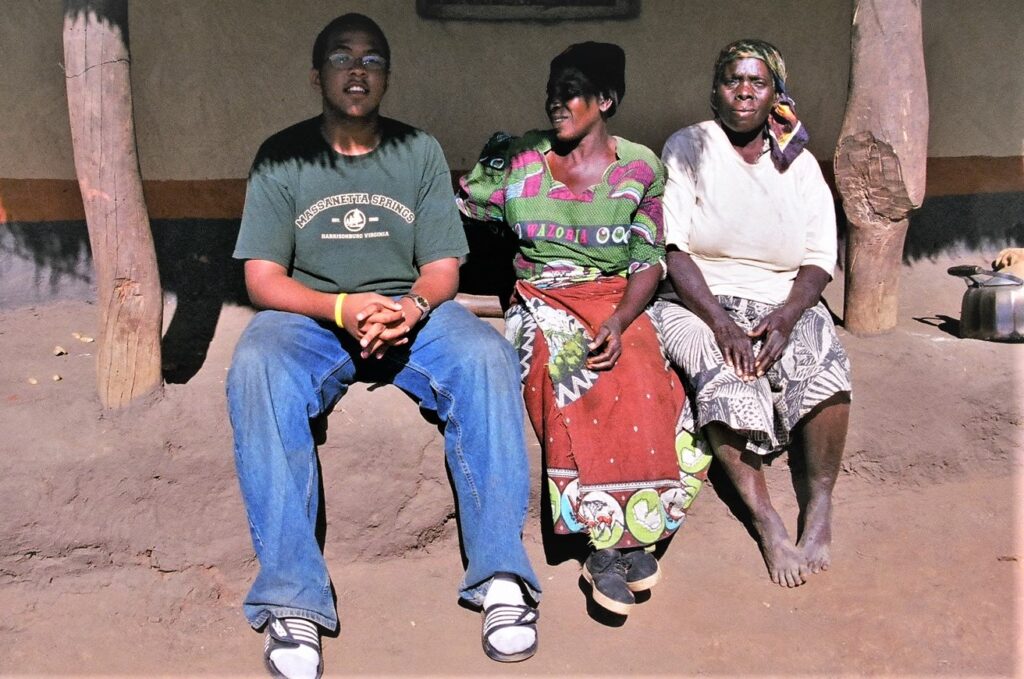

The kinship relationship through the family and clan your born into provides support from when the individual is a child, an adult, and up to old age. Besides the 2 biological parents of mother and father, the bond of kinship network provided individual identity and a source of vast support involving clans in two different villages. These two villages sometimes may have a population of 300 men, women, and children in each of the villages of the groom and bridegroom.

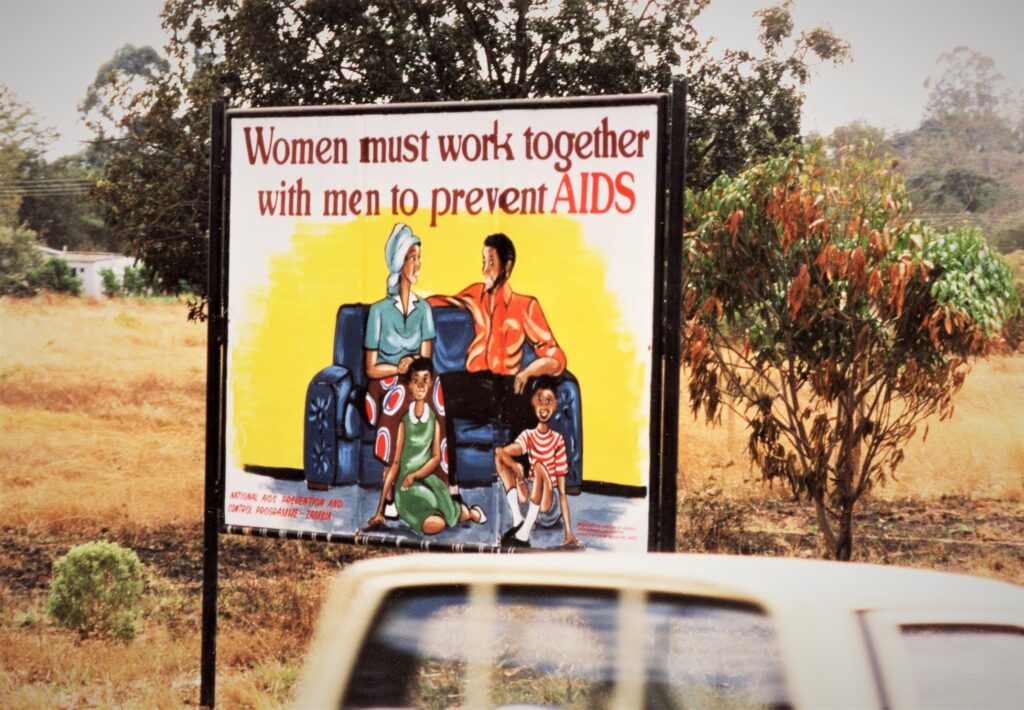

The kinship relationships embedded in the clans and villages provided many advantages in life. Kinship provided the individual a place to live, food, clothing, social guidance, land for farming and provision of food, social support during difficult times such as death, being orphaned and during illness. In the 1800s when wars and conflict were common, kinship provided security from threats from external sources from the village such as war and wild animals. Kinship provided you with help during marriage in terms of providing lobola, celebrations such as marriage weddings, child birth, and support when attending school.

Perhaps the most important aspect of kinship relationships and terms that are used is that they defined obligations to the people who shared the bonds. Fathers and mothers treated all their sons and daughters warmly with obligations to support all the their daughters and sons with love. Brothers and sisters supported each other and enjoyed their relationships and especially obligations. One thing which is very significant is that in all the kinship relationships described, there were never any step fathers, step mothers, step sisters, step brothers, or half brother or half sister, or adopted son, adopted daughter, and adopted niece. Of course if people ask how the two people are related, they may explain some details of the background mentioning names. But the reality that someone was not biologically related to you, was never the focus of the kinship relationships and bonds. This is why in the Zambian/African traditional societies, even today, it is possible to have so many fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, grandmothers and grandfathers.

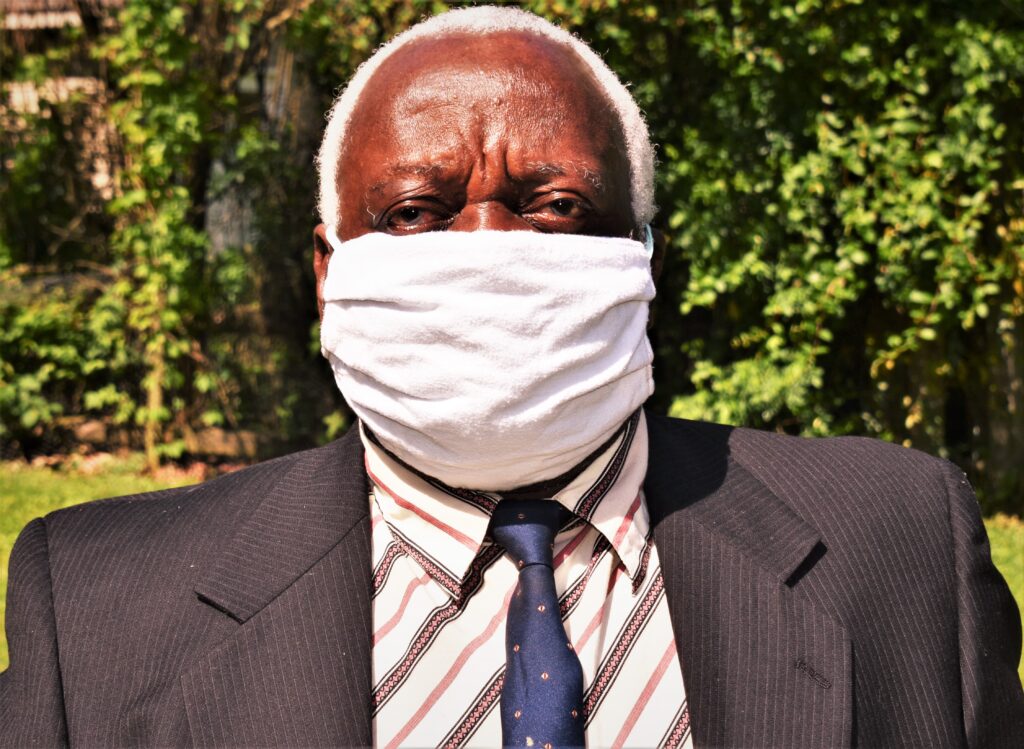

Kinship Relationship Today

Although many of the traditional Zambian/African kinship terms are used, their used has been vastly urbanized and Westernized. Kinship terms such as mother, father, daughter, son, nieces and nephews are used mainly in the small nuclear biological monogamous family. Kinship relationships in the extended family outside the immediate nuclear family are less emphasized and less prominent. The use of uncle, niece, step-mother, step-sister, and half-brother are now very common in urban Zambia with very little link to their traditional uses as described. This may signal the weakening of kinship bonds that were very strong all the way to the 1960s and 1970s.