Advice for African – Americans

When I accepted the invitation to speak at this conference, I was initially very excited. But then it occurred to me: “What advice can I give to African-Americans on matters of education? This society is one of the most advanced countries in the world. It has sent men to the moon, has sophisticated technology, the country spends billions of dollars on education, it has people and especially experts who dissect issues using sophisticated words and brains that offer equally sophisticated solutions to some of the simplest problems. What would African-Americans learn from an African who obtained his early education in an African village?

As a Sociologist, I could bombard you with high falutin, complex advice that gives you a zillion possible options as solutions. But instead, I want to share with you what worked for me and millions of Africans, what inspired or sparked me to go to the village school when I went to my very first grade?

Why are my experiences with obtaining education in an African village relevant to African-Americans? Africans in a village and African-Americans in the United States share common problems: material poverty and negative experiences with European racism. But in many cases this is where the similarity ends. Throughout my presentation I will continue to make comparisons between the African village and an African-American school system located maybe in an inner city or relatively poor neighborhood. The inner city is chosen here as it is often presented as a microcosm of what is wrong with education among African-Americans; poverty, crime, drugs, single parenthood, and welfare dependency. As to whether this is only characteristic of African-Americans only and not any other groups is another story.

What are the factors that contributed to my getting a good education in an African village?

- Having strong parents, family, and stable community.

- Good teachers who understood me and my peers

- Teachers who were the best, had done it, and could inspire me to do and achieve the best.

- A good, stable, and safe physical environment surrounded by nature, pleasant sound, sights and smells, and low noise levels.

- Money and teaching materials.

First, my obtaining a good education in my African village had something to do with having a very strong nuclear and extended family in the village located within the larger context of an equally strong community of responsible adults. This strong family and community had well spelt out norms, values, customs, and traditions. What the strong family did for me is what clinical psychologist Brehony (1996) calls providing a “container” that always helps to keep all of us safe and have a strong and comfortable sense of belonging.

This strong family bond made it possible for my father, who was away from the village teaching at the time, to send word to my grandparents in the village to send me to school. My uncle took me to school. I remember that I washed that day and wore my new khaki school uniform. I was about five years old. I was excited. My uncle clutched my little hand and walked me to school. At the class room door, he handed me over to the teacher and the class was already in session. This had a very important symbolic significance. This was like the way the bride walks with her father down the aisle in church during the wedding and symbolically “gives the bride” away to the groom. That was probably a very important signal of how important education was to my family: “Me being handed over to the school.”

This strong family bond made it possible for my father, who was away from the village teaching at the time, to send word to my grandparents in the village to send me to school. My uncle took me to school. I remember that I washed that day and wore my new khaki school uniform. I was about five years old. I was excited. My uncle clutched my little hand and walked me to school. At the class room door, he handed me over to the teacher and the class was already in session. This had a very important symbolic significance. This was like the way the bride walks with her father down the aisle in church during the wedding and symbolically “gives the bride” away to the groom. That was probably a very important signal of how important education was to my family: “Me being handed over to the school.”

This also illustrated the important and strong role of good parenting in acquiring a good education. The family and community provided frequent reward, praise, and encouragement. Every child and student needs that. If a child who is trying to get a good education is frequently told: “You will never amount to anything”, “You are wasting your time”, if a child tries to learn proper English; “You are becoming “Whitey” or “What are you trying to become?” or using some other pejorative statements, how can a child get a good education?

I remember after the first term when I did well in my first grade class, the warm praise I got from adults in the village. My aunt proudly carried me on her back and she said: “I am carrying on my back a very smart husband. When he grows up, he is going to get a job and he will buy us blankets and clothes.”

I remember after the first term when I did well in my first grade class, the warm praise I got from adults in the village. My aunt proudly carried me on her back and she said: “I am carrying on my back a very smart husband. When he grows up, he is going to get a job and he will buy us blankets and clothes.”

Parents need to show concern and sacrifice not by simply yelling at the child to “Do your home work!” but by actions that demonstrate to the child that the parent is really interested in the child getting the education. One example makes me shed tears today. When I was going to school, we used to attend boarding school. We traveled by bus at the beginning and end of the school holidays. My father always escorted me riding his bike carrying all the heavy luggage, while I rode my bike carrying the lightest load. This one day we waited all day by the side of the road and the bus never showed up. It became cloudy, it was getting late in the day, and it began to sprinkle. My father had to be at work the following day at eight a.m. He asked one of his friends whether I could sleep at his house and catch the bus the following morning. As it was getting dark, my father bid me farewell and rode his bike through the bush path until the tall grass swallowed him. He was going to ride through ten miles of bush and pitch darkness and rain to get home so he could be at work the following morning. He had suffered and endured all of that all day just for me. This happened many times as I grew up. A million words could not have demonstrated how much my father loved and wanted me to get a good education. How could I disappoint him? In his book: The Road Less Traveled, Peck (1978) calls this as willingness of parents to “suffer along with their children” (p. 23) as one of the most important ways parents can demonstrate genuine love for their children. This is also said to be the beginning of self-discipline.

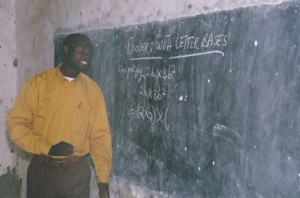

Second, when I got my good education in the village, I had good teachers who understood me and my peers. This means teachers who were familiar with our backgrounds, knew our homes, parents, language, customs, and traditions. This means that teachers reinforced the positive values, customs, norms, and traditions of my community. Teachers did not say: “The education you are getting will teach you to ignore or belittle your elders, language, and values of the community.” This also meant that teachers could teach using styles and methods that were appropriate and familiar to us. Storytelling and algebra is a good example. Do African-American children have teachers who understand them? I have not conducted a survey on this but if the searing controversy over “Ebonics” a few months ago is any indication, I have my doubts. But I will leave this as a rhetorical question.

Second, when I got my good education in the village, I had good teachers who understood me and my peers. This means teachers who were familiar with our backgrounds, knew our homes, parents, language, customs, and traditions. This means that teachers reinforced the positive values, customs, norms, and traditions of my community. Teachers did not say: “The education you are getting will teach you to ignore or belittle your elders, language, and values of the community.” This also meant that teachers could teach using styles and methods that were appropriate and familiar to us. Storytelling and algebra is a good example. Do African-American children have teachers who understand them? I have not conducted a survey on this but if the searing controversy over “Ebonics” a few months ago is any indication, I have my doubts. But I will leave this as a rhetorical question.

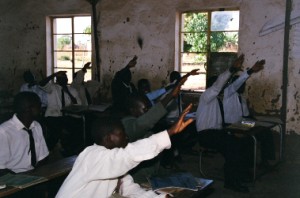

Third, when I was getting my education in the African village, I had teachers who had done it, and could inspire me to do and achieve the best. These are the teachers who inspired dreams and sparked my sense of imagination. Today, people call adults like these mentors or role models. It is very crucial to have teachers or a teacher like these along every African-American student’s life because without them school becomes a worthless and meaningless chore or routine. American educators today and the public would find it ironic that one of the teachers who were a disciplinarian when I was in primary school was also the one that was most inspirational to me. Today some of the discipline is called child abuse and teachers do get sued. Again I am not advocating mass beatings of students for every small reason, I am just telling you of my experiences.

Third, when I was getting my education in the African village, I had teachers who had done it, and could inspire me to do and achieve the best. These are the teachers who inspired dreams and sparked my sense of imagination. Today, people call adults like these mentors or role models. It is very crucial to have teachers or a teacher like these along every African-American student’s life because without them school becomes a worthless and meaningless chore or routine. American educators today and the public would find it ironic that one of the teachers who were a disciplinarian when I was in primary school was also the one that was most inspirational to me. Today some of the discipline is called child abuse and teachers do get sued. Again I am not advocating mass beatings of students for every small reason, I am just telling you of my experiences.

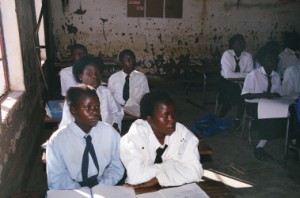

Fourth, when I was getting my good education in the African village, I had a good and safe physical environment surrounded by grass, trees, beautiful streams in which we swam and fished, singing beautiful birds, pleasant sounds of dance and music, and sights and sounds that were nourishing to the soul. We also had a good spiritual life. How can any child get a good education when there is fear in their heart about being victims of possible violence in school, use of foul and violent language, intimidation, loud noise, guns, and perhaps surrounded by physical ugliness? Is this good for the soul let alone for a good education?

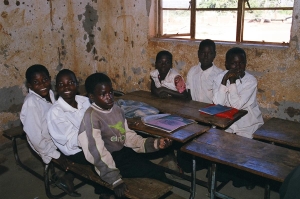

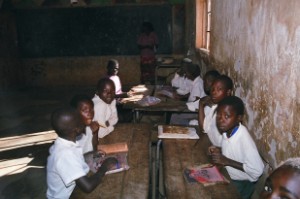

Fifth, when I was getting my education in the village, money and adequate teaching materials were necessary. Today, money and teaching materials are seen as essential for any child who wants to get a good education. But it will come as a shock to you that in the village school I attended, the materials were inadequate. Text books were often few, old and torn. Sometimes we shared one text book among three to five students. Pencils and paper had to be economized. The important point here is NOT that money and teaching materials are not important, but that there are other factors which may be more important than just having plenty of materials. I have heard of so many cases where private parochial schools spend two thousand dollars per annum per student have educational scores that surpass that of a public school where six thousand dollars may be spent per annum per student. There are cases in this society today where a poor school, perhaps through court mandates, may be given top of the art computers, plenty of books, swimming pools and other sports facilities and all the material necessities. But students do not necessarily learn more to improve their academic performance.

Fifth, when I was getting my education in the village, money and adequate teaching materials were necessary. Today, money and teaching materials are seen as essential for any child who wants to get a good education. But it will come as a shock to you that in the village school I attended, the materials were inadequate. Text books were often few, old and torn. Sometimes we shared one text book among three to five students. Pencils and paper had to be economized. The important point here is NOT that money and teaching materials are not important, but that there are other factors which may be more important than just having plenty of materials. I have heard of so many cases where private parochial schools spend two thousand dollars per annum per student have educational scores that surpass that of a public school where six thousand dollars may be spent per annum per student. There are cases in this society today where a poor school, perhaps through court mandates, may be given top of the art computers, plenty of books, swimming pools and other sports facilities and all the material necessities. But students do not necessarily learn more to improve their academic performance.

MITIGATING FACTORS

I do not want to give the impression of giving idealistic advice. I realize that the reality is different in American society of  the 1990s. Families and communities are dislocated, good teachers cannot be retained in schools that are in poor neighborhoods, the physical environments in which some African-Americans live may be dangerous and hazardous; drive by shootings, drugs, and poverty. The legacy of racism and slavery in many cases is still there. It is folly to throw your hands up in resignation. As education, especially public education, is often used as a pawn by various political and other interest groups, no wonder nothing seems workable. Take for example, a few years ago. A beaten down and beleaguered inner city public school in Detroit wanted to do something to encourage young boys to stay in school and to focus on education. They were going to try a boys’ academy for elementary school African-American boys. There was a fire storm of controversy about the constitution, gender discrimination, and abuse of public funds. I do not know what happened. I remember that the experiment was halted.

the 1990s. Families and communities are dislocated, good teachers cannot be retained in schools that are in poor neighborhoods, the physical environments in which some African-Americans live may be dangerous and hazardous; drive by shootings, drugs, and poverty. The legacy of racism and slavery in many cases is still there. It is folly to throw your hands up in resignation. As education, especially public education, is often used as a pawn by various political and other interest groups, no wonder nothing seems workable. Take for example, a few years ago. A beaten down and beleaguered inner city public school in Detroit wanted to do something to encourage young boys to stay in school and to focus on education. They were going to try a boys’ academy for elementary school African-American boys. There was a fire storm of controversy about the constitution, gender discrimination, and abuse of public funds. I do not know what happened. I remember that the experiment was halted.

I went to a boys’ boarding school. When I was fourteen years old, I spent most of the day thinking about my girl friend who was ten miles away at another girls’ boarding school. What would have happened if that girl had been sitting next to me in class? Would I have pulled all those A’s to be able to go to college? I doubt it.

I went to a boys’ boarding school. When I was fourteen years old, I spent most of the day thinking about my girl friend who was ten miles away at another girls’ boarding school. What would have happened if that girl had been sitting next to me in class? Would I have pulled all those A’s to be able to go to college? I doubt it.

The point I want to emphasize is that all of us as individuals can DO something. Do not wait for some big solution from someone in Washington, D.C. or some think tank. Solutions often lie within the grasp of individuals.

- You can start by creating a good and strong family and community. Let adults take charge of the community. This will discourage the grip of gangs on schools and communities.

- Avoid titillating images of the TV that often encourage violence and glamorize it under- cutting the values that you know are right for your family.

- Attract good people to live in all neighborhoods; raze all these inner city public housing units.

- African-American Education ought to go beyond the SATs and going to college and getting a job. There is a world out there of international competition and job market.

REFERENCES

Brehony, Kathleen A., Awakening at Midlife: RealizingYour Potential for Growth and Change, New York: Riverhead Books, 1996.

Peck, M. Scott, The Road Less Travelled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978.

Steele, Shelby, The Content of Our Character: A New Vision of Race in America, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.