African Disease Healing Methods – Part 1

The Germ and Icobasco Approaches to Disease: Comparative Exploration of Zambian/African Traditional and Western Healing Methods among the Tumbuka of Zambia

ABSTRACTA sample of 118 adults responded to a questionnaire, which had open ended and structured questions. The respondents were randomly chosen from 32 villages located among the Tumbuka people of Chief Magodi of the Lundazi District in the Eastern Province of rural Zambia in Southern Africa. The study had four major objectives. First, to determine what types of illnesses the Tumbuka describe as exclusively indigenous and only treatable by traditional African/Zambian healing methods and rituals. Second, to determine what types of illnesses the Tumbuka describe as modern or Western and best treated in the modern clinic or hospital. Third, to determine what are the perceived causes of the illnesses that are best treated by the ng’anga or traditional healer. Fourth, to determine what are the perceived causes of the illnesses that are best treated at the modern clinic or hospital.

The Germ-chemical (Western) and Icobasco (African) perspectives were used in conceptualizing how Africans may perceive disease and strategies for treatment. The findings suggest that the Tumbuka people may have significant dualism in the way they explain the causes and treatment of disease. They characterize certain types of disease as being modern and therefore only treatable at the clinic or hospital. Others are characterized as traditional or indigenous and therefore only treatable by the ng’anga or traditional healer. Although these two conceptualizations correspond to the Germ-chemical and Icobasco perspectives respectively, the findings also suggest that the dualism the Tumbuka exhibit may not be rigid and may often be mitigated by a multicausal, flexible, and complex approach to and the treatment of such diseases as pneumonia, coughing, malaria, chronic pain, seizures, and HIV-AIDS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Laura Zarrugh for her significant comments on the first draft of this research report. Panel participants at the Virginia Social Science Association (VSSA) annual conference at Newport News University gave me good feedback during the first public presentation of the report in March 2003. The research proposal benefited from comments from Dr. Harriett (Betsy) Hayes, Dr. Susen Piepke, and Dr. Arthur Gumenik who are all colleagues at Bridgewater College. Dr. Carl Bowman, a colleague at Bridgewater College assisted in responding to questions during the SPSS data entry procedures and also in his capacity as Dept. Chair in helping with providing a student assistant, Ryan Bachman, in entering and transcribing the data. The sabbatical research fieldwork in the villages would not have been possible without the assistance of the following: Mr. J.B Kasolola (Dr.) the traditional healer for providing me with information on the procedures traditional healers follow when treating patients. Mr. Vincent Tembo and Mr. Zuza who were very hard working and patient research assistants, Mr. Nyirenda, the Medical Assistant at Nkhanga Clinic, for giving the research team complete access to clinic records, my parents Mr. Sani Zibalwe and Ms. Enelesi NyaKabinda for being there back at my home village and engaging in informal conversation about traditional healing at the end of a long day of field work. Mr. Zebby Tembo showed me invaluable information about traditional herbs and rituals for curing illness. Mr. And Mrs. J. J. Mayovu, Suzgho Mayovu and Martha Mayovu in Lusaka were very helpful in cross-translating the Tumbuka indigenous African language questionnaire into English. I would like to thank all the respondents in the villages for the time they devoted to respond to the research team’s questions. I appreciate my wife Beth, and my children Temwa, Kamwendo and Sekani for their support and patience during my absence to Zambia during August and September of 2002 when I conducted the fieldwork. Finally, I would like to thank all those who helped but have not been directly acknowledged or mentioned.

INTRODUCTION:

Since the discovery of HIV/AIDS in 1981, interest in health, healing, and how the immune system works has increased and intensified (Smilgis, 1987; Gallo, 1991). This is because the HIV/AIDS disease does not have a cure. Therefore medical scientists are making concerted efforts to find a vaccine and cure for HIV/AIDS. But this trend has also sparked interest and refocused attention on what is known as alternative medicine. This includes such healing methods as herbal medicine, acupuncture, chiropractic, homeopathy and many others (Mindell, 1999). This is a research report of a comparative investigation of Zambian African traditional healing methods among the Tumbuka of the Eastern Province of Zambia in the context of social change and modern Western medicine. The Western Germ Theory and the African Icobasco Theory are used to explore the nature and comprehension of disease among a sample of Africans. The information collected from this research field work makes a tremendous contribution to understanding and expanding medical epidemiological knowledge about illness, cure, and healing rituals and beliefs involved in some of the contemporary illnesses like the HIV/AIDS pandemic, childhood diseases, parasites and hygiene-related illnesses, mental disorders and other serious chronic illnesses. The author conducted fieldwork in August 2002 in the Lundazi district of the Eastern Province of Zambia.

The report defines the problem, states the objectives of the study, describes the methodology, presents and discusses the findings.

DEFINITION OF PROBLEM:

Since the introduction of Western life styles in Africa through Western colonialism (Bohannan and Curtin, 1988) and now contemporary globalization (McMichael, 2000), there has been a pronounced duality in the way Zambians cure illness. On the one hand and under certain circumstances, the people use indigenous or traditional methods, which primarily use herbs and rituals. On the other hand, they use Western methods and approaches, which are prevalent in modern clinics and hospitals. This duality means the two approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of illness coexist among Zambians; the Germ and the Icobasco approaches.

The study determined the repertoire and range of choices Africans/Zambians make when they seek treatment of illnesses. The choices may range from initially using the common herbs to consulting the services of a traditional healer. The individual may also seek treatment from the local clinic and may be referred to the local district hospital. The study ultimately determined how healing is achieved. What do the Tumbuka perceive as causes of illness? What types of illnesses prompt the Tumbuka people to seek a traditional healer and for which ones do they seek modern clinic or hospital treatment? What are the healing methods, procedures, and rituals traditional healers employ? What herbs are used for what diseases? Do the Tumbuka consider certain diseases as traditional or indigenous and others as modern like HIV-AIDS? After conducting the survey, interviews, and some limited field observations, the knowledge from this study may help understand how contemporary rural Africans conceptualize disease, and how they make choices of treatment. The findings will also enhance the bank of and the judicious use of alternative medicine.

The study determined the repertoire and range of choices Africans/Zambians make when they seek treatment of illnesses. The choices may range from initially using the common herbs to consulting the services of a traditional healer. The individual may also seek treatment from the local clinic and may be referred to the local district hospital. The study ultimately determined how healing is achieved. What do the Tumbuka perceive as causes of illness? What types of illnesses prompt the Tumbuka people to seek a traditional healer and for which ones do they seek modern clinic or hospital treatment? What are the healing methods, procedures, and rituals traditional healers employ? What herbs are used for what diseases? Do the Tumbuka consider certain diseases as traditional or indigenous and others as modern like HIV-AIDS? After conducting the survey, interviews, and some limited field observations, the knowledge from this study may help understand how contemporary rural Africans conceptualize disease, and how they make choices of treatment. The findings will also enhance the bank of and the judicious use of alternative medicine.

Second, the knowledge may help bridge the gap and conflict between the use of African traditional healing methods and Western medicine. There is an increasing realization that diseases including HIV/AIDS, chronic illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome, migraine headaches, chronic pain, certain seizures, mental illness and many others may be better treated combining the best from alternative African traditional healing methods and Western medicine (PBS, 1993). Rural Zambia in Africa is an appropriate place to assess the complexity of the impact and status of these two medical epistemologies.

DISEASE EPISTEMOLOGIES:

Germ-chemical Perspective

There are two types of illness and healing epistemologies, which may be in competition, complementary, or supplementary depending on the circumstances in the lives of Africans and Zambians. The first one is what might be termed the Western germ-chemical epistemology. This perspective argues that the principle causes of illness and disease are germs in the form of bacteria, viruses, and parasites (Mores, 1977; Fettner, 1990; Karlem, 1995; Kolata, 199; Tierno, 2001). When all or some of these germs invade the human body, the immune system goes into gear and tries to fight to eliminate them or limit their impact on the proper functioning of the body (Benjamini, Sunshine, and Leskowitz, 1996). The germ-chemical perspective exclusively and strongly endorses the use of chemical medicines in the form of pharmaceutical drugs and surgery to effectively eliminate and control the germs or some of the symptoms of illness that are generated by the invasion of the body by viruses, bacteria, and parasites. Vaccinations and immunizations are routinely used to further preempt the potential impact of the germs. This is how prevention of illness and healing of the body are primarily achieved. The germ-chemical perspective argues that people simply have to acquire knowledge about how the germs operate, and seek help from medical doctors in clinics and hospitals whenever they are ill in order to maintain sound health conditions.

Icobasco Perspective

Witchcraft is probably one of the most abused, misused, and misconstrued concepts to be used to paint the whole of Africa and Africans with a broad negative brush. First and foremost, scholars and lay people define witchcraft as the belief that humans are capable of invoking, practicing and exercising a psychic force for the primary source of hurting or killing other humans, and engaging in other malevolent activities. The belief also is that those who practice the craft collectively engage in nocturnal clandestine activities that include communal rituals such as cannibalism at graveyards, transforming themselves into animals at night or harming innocent others in their sleep. “A witch is believed to change into other forms like those of animals, reptiles, birds. The magic is usually administered at night. Witches are invisible except to those who have medicine to see them” (Ngulube,1989:28). Ordinary people cannot see or detect the activities of witches because one needs to be a witch or use medicines in order to detect or observe the witch.

Witchcraft is probably one of the most abused, misused, and misconstrued concepts to be used to paint the whole of Africa and Africans with a broad negative brush. First and foremost, scholars and lay people define witchcraft as the belief that humans are capable of invoking, practicing and exercising a psychic force for the primary source of hurting or killing other humans, and engaging in other malevolent activities. The belief also is that those who practice the craft collectively engage in nocturnal clandestine activities that include communal rituals such as cannibalism at graveyards, transforming themselves into animals at night or harming innocent others in their sleep. “A witch is believed to change into other forms like those of animals, reptiles, birds. The magic is usually administered at night. Witches are invisible except to those who have medicine to see them” (Ngulube,1989:28). Ordinary people cannot see or detect the activities of witches because one needs to be a witch or use medicines in order to detect or observe the witch.

This research report argues that the so-called “witchcraft” has been misused in a highly pejorative way in the depiction of Africans/Zambians in a rather broad and careless way. In African tribal communities, witchcraft and other closely related practices like sorcery and magic are believed to have a repertoire of functions on a continuum. On the one negative extreme, witchcraft is believed to be responsible for mindless death and extreme social discord through persecution of innocent citizens. On the positive extreme, witchdoctors help cure ill-stricken citizens and act as a positive force or antidote against the otherwise debilitating fear of witchcraft (Evans-Pritchard, 1976). Many anthropologists and other scholars have consistently emphasized the positive functions of the belief in witchcraft and the role of the witchdoctor in the African society. This report asserts that the “witchdoctor” in the traditional African society is the “traditional” healer who has much of the antidote against witch-induced or caused illnesses.

It makes significant sense to investigate the role of the traditional healer in witch-induced illness because it is still a very dominant way of comprehending the cause of disease both in urban and rural Africa. Discussing the belief in witchcraft in the contemporary Zambian society of the late 1980s, Ngulube (1989:24) says,

The belief cuts across the spectrum of time in the past, present and indeed future. Any person who has the power to kill others with magic charms is a witch. Witchcraft is the entire practice of such powers. The belief in witchcraft is as hot today, as it was when missionaries came and at the attainment of Zambia’s independence. It is one belief, which has not been affected in any way by modernization. In fact, it seems that belief and fear of witchcraft are marching concurrently with the march towards industrial development and technological development.

Since the majority of Africans, in spite of acquiring formal Western education, still believe in witchcraft and witchdoctors, investigating the role of both is a matter of great urgency and importance. There are two developments that may make this approach more productive. First, higher formal education does not destroy African belief in African traditional epistemology, including witchcraft beliefs. Confirming the observation of wide witchcraft belief in Africa, Parrinder (1963:128) says “To the African they are still part of the traditional ideas of his country, and there is little sign of a decrease in witchcraft belief with increasing education.”

Second, modern medical facilities may never be enough to treat many of the illnesses let alone those ailments whose etiology may be partly cultural specific. This study investigates and characterizes the entire epistemology of the African indigenous cultural specific conceptions of illness including witchcraft and other indigenous causes as Icobasco. In this report witch-induced illness is synonymous with Icobasco.

Witchcraft in this report is defined as any individual cognition of illness in which the individual strongly believes that conflict with other significant close social acquaintances and relatives in his or her life are suspected perpetrators. Their motives for inflicting the illness may include jealousy, envy, consequences of infidelity, cruelty, malice, spirit possession, or breaking traditional taboos (Ngulube, 1989). In some cases the individual’s behavior may have wronged ancestral spirits. The individual would be experiencing Illness Cognition Based on Social Conflict. A traditional healer can only cure this particular illness. This report argues then that the disease that is caused by African Illness Cognition Based on Social Conflict (ICOBASCO) can only be most effectively cured by traditional healers.

How does belief in Icobasco determine the African’s understanding or conception of illness and well-being? The crucial centerpiece of the argument in this report is that Illness Cognition Based on Social Conflict (Icobasco) has remained a central cornerstone of African epistemology. This is more so in the interpretation and understanding of disease and well-being. Exposure to higher Western education or embracing some of the Western practices seems not to have diminished the belief in Icobasco and the traditional healer. The term some Zambians use is “va banthu”, referring to persistent illness that defies modern medical treatment or diagnostic tools. The suspicion is that the disease is human or “munthu” caused with deliberate malevolent motivation and can only be cured by a traditional healer.

The Icobasco perspective argues that African cognition of both individual well-being and the state of being ill depends on cues learned in the context of African traditional social upbringing (Tembo, 1993; Some, 1998). These include growing up in a social environment in which interpersonal relations are emphasized, group beliefs and communal obligations to members of the family are supreme, and the African child and adult grow up with a strong recognition of the efficacy of community worldviews and extended family values (Mazrui, 1986). Because of this high degree of interdependency and symbiosis between the individual and community, especially the extended traditional communal family, the African is more likely to incorporate and appropriate the group cognitive style including a strong belief in Illness Cognition Based on Social Conflict (Icobasco). This second epistemology, which co-exists with the Germ approach among the Tumbuka, might be termed Illness Cognition Based on Social Conflict (Icobasco). Cognitive and developmental psychology (Triandis and Heron, 1981) are both pivotal in exploring and understanding the significance of African Cognition of Disease Based on Social Conflict (Icobasco) or witchcraft in African society, especially its possible contribution to diagnosing, curing, and healing of illness.

According to the Icobasco perspective, the cause of illness is social conflict with any significant others in the community (Ngulube, 1989). The cure of the illness and healing are achieved through the nga’nga, or traditional healer, or shaman using herbs and rituals.

Previous studies conducted in the area suggest that people in the villages may have common perceptions of illnesses that are prevalent in the community compared to those frequently reported at the local clinic (Tembo, 1982).

TABLE 1

Rank Order of Diseases Most Frequently Diagnosed or Reported 19822

| VILLAGER’S RANK ORDER LIST | CLINIC RANK ORDER LIST |

| Coughing | Malaria |

| Dysentery (for children) | Simple Cough |

| Diarrhea | Abdominal Pains |

| Malaria | Injuries |

| Sore eyes | Other skin diseases |

| Bilharzia | Diarrhea |

| Sores | Eye infections |

| Ear Sores (Mphenga) | Tooth-ache |

| Ear Disease | Worm infestation |

| Polio | Ear trouble |

| Toothache | Malnutrition |

| Stomach-ache | Ulcers |

| Swelling legs | Bilharzia |

| Vomiting | Bronchitis |

| Pneumonia | Venereal Diseases |

| Back-ache | Pneumonia |

| Other diseases | |

| Chicken-pox | |

| Scabies | |

| Measles | |

| Other fevers | |

| Other infections | |

| Leprosy | |

| Jaundice |

A comparison of the two lists in Table 1 shows generally that the villagers’ perception of the most common diseases is also reflected in the clinic’s records. HIV/AIDS does not appear in either list because the study was conducted in 1982 before HIV/AIDS became a world-wide epidemic. One exception in the table is that worm-infestation does not feature in the villagers’ list. This suggests that the villagers may not directly perceive diseases that might require expert diagnosis by Western medical technology. However, worm infestation might be perceived in the symptoms associated with stomachache for example. Likewise, malnutrition, which does not feature in the villagers’ list, might be reflected indirectly through sores and many other malnutrition-related diseases. Similarly, injuries feature very prominently on the clinic’s list. If the injured person does not recover quickly; perhaps due to malnutrition, villagers most likely regard the wound as a sore.

Villagers also initially suggested that they shared the modern germ-chemical perspective of illness by responding in the survey that the diseases could be prevented by drinking clean water through boiling, eating good food, wearing clean clothes and keeping the body clean and using pit-latrines or out houses. However, the villagers in the study expressed doubt at the same time about the validity of the preventive measures. The study reported:

One point was that townspeople drink clean water and have cleaner environments, but why do they still fall sick? Some respondents persistently misunderstood prevention by insisting that having a hospital or clinic was the solution. Some respondents even went to the extent of saying that disease cannot be prevented and that preventive measures they had endorsed were only to satisfy the expectations of us (researchers) modern or educated people. (Tembo, Mwila, and Hayward, 1982: 15)

This ambivalence suggests that the villagers may have different attributions for the causes of illness and disease perhaps including Icobasco. In an interview with a local traditional healer, indigenously known as ng’anga, the possibility or likelihood that there might be two or more or multiple causes and treatment of illness in contemporary Africa or Zambia was suggested (Tembo, 2000) 3. The causes correspond with the two epistemologies identified earlier.

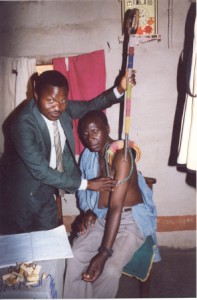

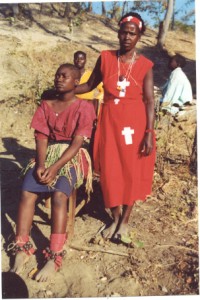

Mr James Nyirenda, popularly known as Dr. J. B. Kasola, is an African traditional healer. He explains that practitioners in modern hospitals have to be explicitly trained to treat patients. But in the traditional healing methods, the healers dream of the prescriptions of trees from which herbal medicines can be obtained for treating illness. In his most poignant remark, JB Kasolola explained that there are certain diseases that modern clinics and hospitals do not know how to cure. He said in the Tumbuka Bantu Zambian language:

“Chipatala kulije mankhwala bakufukizgha, chifusi, muchezo”.

– modern hospitals do not have a cure for some of our indigenous diseases like bakufukizgha, chifusi, and muchezo.

“Ise para banthu balowana tikuwirapo.” – we as traditional healers, when people bewitch each other we intervene to cure the victim. We as traditional healers never give injections to our patients. If a patient comes to me with a complex illness, I will treat the illness that is best treated by me as a traditional healer. I will then send the patient away to the clinic nearby where modern diseases may be best treated. (Nyirenda, 2000)

J. B. Kasolola designates himself as a member of the Traditional Healers Practitioners Association of Zambia. (THPAZ). The traditional healer’s views underscore the fact that, there may be atleast two competing or complimentary illness and healing epistemologies among the Tumbuka. There are some diseases that are caused by germs and they may warrant the use of the germ-chemical repertoire of treatment available in this perspective. These are the modern or new diseases. The patient may then visit the local clinic to seek treatment, cure, and healing. The Icobasco perspective is the one J.B Kasolola alluded to. These are complex diseases that have indigenous causes including bewitching, the breaking of traditional sexual and other social taboos, social conflict, and therefore warrant only the use of the repertoire of services of the traditional healer. These are the traditional or old diseases.

In this study, the modern or new diseases are the ones respondents said had emerged only as recently as the last thirty to forty years. These include diseases respondents mentioned by name such as AIDS, certain types of pneumonia, TB, diarrhea, malnutrition, yellow fever, headache and certain types of cough. One common criteria of the definition of a modern disease among the Tumbuka is that the disease can be treated easily at the clinic using modern medicines. If the disease is persistent or defies clinic treatment, it may easily be re-characterized as indigenous or Icobasco-caused.

In this study, traditional, old, or indigenous diseases are ones that respondents characterized as having been around for as long as the respondent or his or her older family and kinship members could recall. These are diseases that are inflicted by others through Icobasco including and especially witchcraft. These are chronic illnesses that are said to defy clinic treatment but only traditional healers or nga’nga can cure. These are such diseases as Cilaso (Old Pneumonia), moto(fire), mphapo (woman can’t conceive), vizilisi (seizures). Some indigenous diseases have no short or one word English equivalents such as mchezo, vifusi, camdulo, Chambo 4. The respondents identified a total of 98 modern (new) and indigenous (old) diseases.

Part 2 of this article continued on next page

_____

2 Source: Tembo, Mwizenge S., Mwila, Chungu., and Hayward, Peter., An Assessment of Technological Needs in Three Rural Districts of Zambia, Lusaka: Technology and Industry Research Unit, University of Zambia, Institute for African Studies, Rural Technological Needs Assessment Survey, Preliminary Report No. 1, February 1982, p.14.

3 This material is from an unpublished interview with Mr. James Nyirenda also known as Dr. J.B Kasolola who is a traditional healer at Chipeni Village in Chief Magodi in the Lundazi District of the Eastern Province of Zambia. The interview was conducted by the author in June 2000.

4 These traditional diseases need more elaborate definitions. The symptoms of mchezo are swelling of the legs or the stomach. It is believed a jealous or evil individual plants some medicines on a path. When the intended victim crosses the medicine then he or she comes down with mchezo. Vifusi is becoming mad or insane because someone bewitched the victim. Camdulo is severe cough that’s very loud and persistent. The victim is usually a child whose father has sexual intercourse with a woman other than his wife but then later handles or touches the child. Chambo is a sexually transmitted disease in which the victim experiences severe pain and may even cry when urinating. The victim becomes thin. The cause is bad herbs inserted in the victim through bewitching.