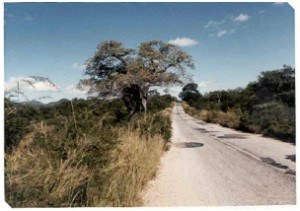

Why am I drawn to this remote African village so often? Why am I in this place in Lundazi many times? Why do I think of this place so often? The bus  journey from the Capital City of Lusaka to the remote Lundazi district is no piece of cake. It is over five hundred miles long on a two-lane road that was paved more than twenty-five to thirty years ago. It’s challenging to drive or ride on a bus as the road is badly damaged in many places. Why don’t I forget this place and enjoy my life in the United States which has so much food, cable TV, medicine, automobiles, cell phones, computer communication, best schools in the world for one’s children, and one can generally expect to live to be in the eighties? After all the cost and hassle of traveling to this remote place I call my home village are overwhelming. But the ten thousand mile flight from the US and the five hundred mile bus journey to my home village has a special place in my heart. Every desolate looking village hut, rural shopping center, the endless farm fields, the wilderness, and thousands of mango trees all hold special meanings for me. I pass places such as Rufunsa, Kacholola, Nyimba, Petauke, Kazimule, Mgubudu Stores, Chipata, Katete, Madzimoyo. Every desolate looking village hut, rural shopping center, the endless farm fields, the wilderness, the baobab tree, hills, roaming goats, and thousands of mango trees all hold special meanings for me. They evoke pleasant memories and rekindle the now ancient excitement of travel away from one’s childhood familiar village. This excitement continues for me to this day.

journey from the Capital City of Lusaka to the remote Lundazi district is no piece of cake. It is over five hundred miles long on a two-lane road that was paved more than twenty-five to thirty years ago. It’s challenging to drive or ride on a bus as the road is badly damaged in many places. Why don’t I forget this place and enjoy my life in the United States which has so much food, cable TV, medicine, automobiles, cell phones, computer communication, best schools in the world for one’s children, and one can generally expect to live to be in the eighties? After all the cost and hassle of traveling to this remote place I call my home village are overwhelming. But the ten thousand mile flight from the US and the five hundred mile bus journey to my home village has a special place in my heart. Every desolate looking village hut, rural shopping center, the endless farm fields, the wilderness, and thousands of mango trees all hold special meanings for me. I pass places such as Rufunsa, Kacholola, Nyimba, Petauke, Kazimule, Mgubudu Stores, Chipata, Katete, Madzimoyo. Every desolate looking village hut, rural shopping center, the endless farm fields, the wilderness, the baobab tree, hills, roaming goats, and thousands of mango trees all hold special meanings for me. They evoke pleasant memories and rekindle the now ancient excitement of travel away from one’s childhood familiar village. This excitement continues for me to this day.

During the early evening night, I sit on the front of my small round hut along the narrow edge known as chiwundo by the thin closed wooden door. The yellow glow of the candlelight is visible along the edge of the rectangular doorframe. The bright half moon is sparkling just above my forehead in the Western side of the star-studded sky. The moonlight creates mesmerizing shapes out of the village huts and the tree. It is serene and calm except for the soft chirps of crickets. The serenity of this place is intoxicating. This must be heaven on earth. This is another evening in my home village. I am savoring every moment like a death row inmate who has been given just an hour to enjoy total freedom before execution.

During the early evening night, I sit on the front of my small round hut along the narrow edge known as chiwundo by the thin closed wooden door. The yellow glow of the candlelight is visible along the edge of the rectangular doorframe. The bright half moon is sparkling just above my forehead in the Western side of the star-studded sky. The moonlight creates mesmerizing shapes out of the village huts and the tree. It is serene and calm except for the soft chirps of crickets. The serenity of this place is intoxicating. This must be heaven on earth. This is another evening in my home village. I am savoring every moment like a death row inmate who has been given just an hour to enjoy total freedom before execution.

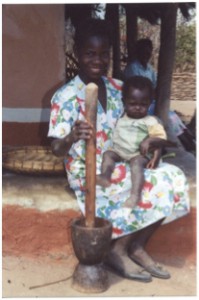

This is the place in which I am related in kinship and family to hundreds of people. This is the place where my mom and dad’s house is literally less than eighty yards away from my house. My brother and his two wives’ houses are sixty yards away. My other brother and his wife and their children are less than twenty yards away. All the dozens of children call me uncle, father, brother, brother-in-law, grandfather, or cousin. Adults call me nephew, brother, grandson, or cousin. Roosters, chickens, and the cacophonous sounds of birds wake me up in the early morning at dawn after a full eight hours of refreshing sleep. The air I breathe in the morning is fresh and crisp. When I wake up in the morning and open my front door, I can see all these people I love at once at a glance. We greet each other every morning. I walk a hundred yards to my mother’s house to wish her and my dad good morning or they to my house some mornings. I am overwhelmed when I realize how much I miss this precious human intimacy.

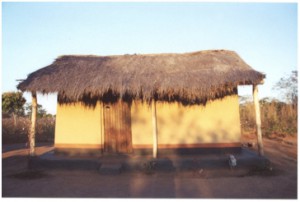

If ever there is such a place that was close to being heaven on earth, it must be Zibalwe Village. The village grass roofed houses are perched on a small elevation in a gorgeous valley ensuring the capturing of cool breezes. The sun shines in the clear cloudless blue sky every day. My small beautiful hut, the size of a small living room of my American house, has a well-manicured dirt yard. My brother’s wives collected the dirt paints of light, red, and black stripes from the tinny creek nearby. As I sit relaxing in the shade in my small structure known as mphungu enjoying the bright sunshine and the cool breeze, I begin to understand something ancient. I can appreciate why people all over the world love home; a place that appeals to your deepest memories and dreams. Home is a place where the cosmos, my restless soul, and my heart are all at peace. Home is a place where death does not seem to matter because one can see the people that gave birth to and one can also see where one would be buried when one dies. A place where every moment or second of the day just feels right. I can now appreciate why the British and other Westerners always grabbed these lands by force and often displaced and killed the native Africans. Life here is surrounded by a unique physical beauty.

If ever there is such a place that was close to being heaven on earth, it must be Zibalwe Village. The village grass roofed houses are perched on a small elevation in a gorgeous valley ensuring the capturing of cool breezes. The sun shines in the clear cloudless blue sky every day. My small beautiful hut, the size of a small living room of my American house, has a well-manicured dirt yard. My brother’s wives collected the dirt paints of light, red, and black stripes from the tinny creek nearby. As I sit relaxing in the shade in my small structure known as mphungu enjoying the bright sunshine and the cool breeze, I begin to understand something ancient. I can appreciate why people all over the world love home; a place that appeals to your deepest memories and dreams. Home is a place where the cosmos, my restless soul, and my heart are all at peace. Home is a place where death does not seem to matter because one can see the people that gave birth to and one can also see where one would be buried when one dies. A place where every moment or second of the day just feels right. I can now appreciate why the British and other Westerners always grabbed these lands by force and often displaced and killed the native Africans. Life here is surrounded by a unique physical beauty.

This is the place where the many acres of fertile land where most of the food is grown is literally four feet behind my house. The land produces abundant corn, kidney beans, sweet potatoes, pumpkins, peanuts, cotton, peas, and cassava. There are numerous mango fruit trees and other succulent tropical fruits like guavas, bananas, and paws-paws during the appropriate seasons.

My five, seven, and nine year old nephews and nieces run and roam long distances around the village fields and bushes, walking three miles to school, playing with incredible freedom within the security of all adults in the six villages knowing and protecting all the children. I appreciate this security and the innocence the children enjoy because I grew up here as a child in the village.

My five, seven, and nine year old nephews and nieces run and roam long distances around the village fields and bushes, walking three miles to school, playing with incredible freedom within the security of all adults in the six villages knowing and protecting all the children. I appreciate this security and the innocence the children enjoy because I grew up here as a child in the village.

But all this security and tranquility is under severe threat of being undone because of the AIDS pandemic and other modern forces. I have followed the AIDS epidemic since 1983. After two weeks of being in my home country and just a few days in several villages conducting research, I have come to a now alarming and predictable observation: too many men and women have died and are dying of AIDS. Unfortunately for the vast majority of the world, the answer will not be as easy as just seeking HIV-AIDS prevention or a vaccine. No doubt this will and would help. There is something that is much more fundamental that developed perhaps over the last thirty to forty years that will have to be acknowledged if the AIDS epidemic will be halted in these villages and perhaps cities: This is the near total breakdown of most of the biological, social, and institutional constraints and organization that traditionally kept a lid on the emergence and spreading out of serious and virulent diseases and epidemics such as AIDS and others. But Zambians and Africans are resilient. My grandfather was mauled by a lion and killed in 1941 trying to defend the people of Zibalwe – my home sweet home village. I contemplate that I am his grandson who lives in America. What would my grandfather have thought of this? Maybe he would not have been too surprised for he was a descendant of the Shaka Zulu, Mzilikazi, and Ngoni peoples who roamed to the area from the Southern tip of the African continent in the late 1800s. After all the first Africans – the Homo Sapiens – migrated thousands of years ago to spread to the entire earth.

I have also now come to understand and appreciate why when Americans and other foreigners truly live in Africa for a while; something always draws them back to the continent. I have often heard people refer to it as a “bug”.