July 14, 2009

During an afternoon in early July of 2009, my twenty year old American sophomore college student son and I finally arrived at the heart of our African culture- our home Zibalwe Village in the remote North Western region of the Lundazi rural district of Zambia in Southern Africa with tremendous joy and relief. The long ten thousand mile trip by air from the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia to Lusaka the Capital City of

Zambia had been in the plans for a year. We traveled by bus from Lusaka to Lundazi which is a distance of

Zambia had been in the plans for a year. We traveled by bus from Lusaka to Lundazi which is a distance of

close to 400 miles. My parents who are in their eighties were now using walking sticks as they got around the village. The numerous uncles, nephews, brothers, sisters, nieces, toddlers in the large kinship network all greeted us with excitement. Some of the young people had grown several inches taller and were in different grades, there were new babies, new marriages and new in-laws, and sadly some relatives were deceased. The on-going harvest season had produced a bounty of corn, red kidney beans, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and plenty of an assortment of fresh and dried vegetables. Many bales of cotton put much needed cash in many homes to buy some clothes, bicycles, and some treats such as tea, sugar, and bread. Sunflower seeds produced enough cooking oil that some mornings we would eat truly fresh French fries with our breakfast as a treat.

That first night when we arrived in the village, my son and I ate delicious fresh and lean village chicken with collard greens with a touch of freshly pressed sun flower oil from sun flower seeds my brother Vincent Tembo and his wife had grown that year. After dinner and heartwarming conversation by the fire that happens between long separated kin, my son and I were ready to go to bed in our little hut. My brother had secured two wooden single beds with mattresses. We made our beds using candlelight and tucked the mosquito nets over them. Mosquitoes and Malaria fever in Zambia and most tropical Africa are still a rampant problem that causes millions of deaths every year.

That first night when we arrived in the village, my son and I ate delicious fresh and lean village chicken with collard greens with a touch of freshly pressed sun flower oil from sun flower seeds my brother Vincent Tembo and his wife had grown that year. After dinner and heartwarming conversation by the fire that happens between long separated kin, my son and I were ready to go to bed in our little hut. My brother had secured two wooden single beds with mattresses. We made our beds using candlelight and tucked the mosquito nets over them. Mosquitoes and Malaria fever in Zambia and most tropical Africa are still a rampant problem that causes millions of deaths every year.

My son reached for the large clay pot by the hut door entrance to get a second glass of the cold drinking water. He took a sip of the water from the clear drinking glass. He told me the water tasted different compared to the last time we had been in the village four years earlier in 2005. In disbelief we looked at the water against a flashlight. Indeed the water was so clear. It used to look murky and had a taste to it which my son said he remembered and preferred. We used to also pour locally bought chlorine in it to kill any water borne germs as the water was drawn from an open ditch.

Since it was late and my brother was asleep in his hut with his wife, we could not ask him about the water. As a joke I told my son that my brother may have sneaked into the small town of Lundazi and bought truckloads of clear bottled water. He had poured it into the large clay pot to impress us since we were from America. We did not think much of this until late the following day.

Since it was late and my brother was asleep in his hut with his wife, we could not ask him about the water. As a joke I told my son that my brother may have sneaked into the small town of Lundazi and bought truckloads of clear bottled water. He had poured it into the large clay pot to impress us since we were from America. We did not think much of this until late the following day.

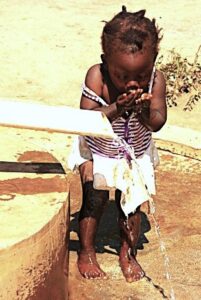

My brother Vincent said he had been keeping the water story secret for us as a surprise and to see if we would notice. My brother announced that he had initiated and organized the professional drilling of a water borehole with concrete around it to replace the old open ditch water well which had contaminated water. The entire village of more than two hundred men, women, and children now drink fresh clean water from deep under the underground aquifer. The old open water ditch was now the watering hole for all the village cows and goats. I was happy, relieved, and stunned. I did not have to worry about contaminated drinking water while visiting the village any more. How was this miracle possible? In all more than 30 years I had lived and visited our village such a possibility seemed too expensive and impossible. At one time fifteen years earlier, I had brought up the suggestion but nothing had come of it. How did my brother Vincent do it?

My 48 year old brother Vincent explained that he had heard of the village program from his travels and word of mouth in the Lundazi rural district. If any village pooled their money and bought 9 bags of cement, provided sand, bricks, labor for crushed stones, and mixing of the sand and cement, a church organization, Church of Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP) would come in and drill the borehole for no charge. The church organization would also provide a hand pump. My brother, without fanfare or any prior public village experience in running difficult-to-organize meetings, quietly organized the village men and women, and when all their ducks were in a row, the church organization was notified and it came and drilled the borehole. Now everyone drinks clean water. Diarrhea is now unheard of and all the children and adults in the village look visibly healthy. My brother attributed his new ability to lead projects to his six week private visit to the United States to visit my family in the Shenandoah Valley in 2003. The trip was particularly difficult because this was barely two years after 9/11. The American Embassy was not about to give a visitor’s visa to the United States to a rural village subsistence farmer. Upon his return, the trip opened new possibilities in life for this man who has barely a ninth grade education. I admire his selflessness and the so many good deeds he is able to do for the entire remote area with so many villages and people. I am so proud of him.

My 48 year old brother Vincent explained that he had heard of the village program from his travels and word of mouth in the Lundazi rural district. If any village pooled their money and bought 9 bags of cement, provided sand, bricks, labor for crushed stones, and mixing of the sand and cement, a church organization, Church of Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP) would come in and drill the borehole for no charge. The church organization would also provide a hand pump. My brother, without fanfare or any prior public village experience in running difficult-to-organize meetings, quietly organized the village men and women, and when all their ducks were in a row, the church organization was notified and it came and drilled the borehole. Now everyone drinks clean water. Diarrhea is now unheard of and all the children and adults in the village look visibly healthy. My brother attributed his new ability to lead projects to his six week private visit to the United States to visit my family in the Shenandoah Valley in 2003. The trip was particularly difficult because this was barely two years after 9/11. The American Embassy was not about to give a visitor’s visa to the United States to a rural village subsistence farmer. Upon his return, the trip opened new possibilities in life for this man who has barely a ninth grade education. I admire his selflessness and the so many good deeds he is able to do for the entire remote area with so many villages and people. I am so proud of him.