Funeral and Burial Customs in Zambia by Mwizenge S. Tembo, Ph. D.

Funeral and burial customs in Zambia vary from the village and city. When a person dies in Zambia, there are customs that are practiced that combine the traditional and the modern or urban that together make the funeral uniquely Zambian or African. As soon as the person is pronounced dead in the hospital or at home in town, the immediate relatives of the deceased will inform the network of all the close relatives in the city as well as villages in the rural areas, and even abroad.

Today a close relative of the deceased will go to the nearest Zambian National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC) Radio and Television to request a public announcement of the death, the address where the funeral is taking place, and any burial arrangements. Virtually every day on ZNBC radio after the main news bulletin of the day, names of deaths are announced with somber organ music. Cell phones, e-mail, and word of mouth among social networks spread the news very quickly.

When the person dies, the body is immediately put in the hospital mortuary or morgue. All the closest relatives in the city or town immediately arrive at the house where the funeral of the deceased will be held.

The grief-stricken closest relatives, host or hosts of the funeral (who could be parents or mother and father of the deceased, uncle, aunt, sister, brother, surviving spouse) sit on the sofa or couch crying, mourning, and sobbing in the living room of their home. The relatives who arrive by foot or by car start mourning aloud as soon as they arrive or get out of the car in front of the house. They will cry as they enter the house. By this time all the neighbors can hear the mourning and all will show up at the home at some point during the funeral period.

The crying or mourning is different from ordinary crying. The loud grief-stricken crying by the men is called kukhuza among the Tumbuka in Eastern Zambia. This is the deep loud crying which is accompanied by the vocal mayi –baba-beeee! mayi –baba-beeee! The crying by the women is called chitengelo. Ye-e—e-e-e-egh! Ye-e—e-e-e-egh! Ye-e—e-e-e-egh! This is a distinctive unique mourning cry by the women mourners that is very rhythmic, distinctive, high pitched, and the most soulful also known as kudinginyika, that can often be heard miles around in rural villages. When anyone hears the chitengelo in the village they can only be hundred percent sure that someone has died because there are no other times that women will cry like that.

Once each of the arriving closest relatives have mourned or cried with the funeral host, they will sit quietly for a while as more close relatives arrive, mourning, and filling the living room couches and and some sit on the floor.

After a few first minutes, the female relatives go to the kitchen to begin preparing meals, accepting food contributions, mealie-meal, and money for buying food and other funeral expenses. They all begin making arrangements to make sure the coming mourners will be fed and relatively comfortable.

Men close relatives gather outside to begin to make arrangements for men’s responsibilities at the funeral. As mourners arrive they make donations that are used for buying fuel for car transportation of mourners being picked up from the bus, railway station, or even the airport. Some men will be assigned to get a truck and to go and get some firewood from the bush for the all night bonfire funeral wake outside the home. Some of the men will offer or are assigned to drive the women from the kitchen to go to the grocery store for bulk shopping for meat, cooking oil, tomatoes, bread, beer, soft drinks, sugar, bags of mealie-meal for cooking large amounts of nshima or any other needs.

The men and women close relatives will coordinate when and where the funeral church service was going to be, burial time and place and the cemetery. Zambia’s Capital City of Lusaka, for example, has two cemeteries: Leopard Hill in the South Eastern part and Chingwere in the Western part of the city. The men go to arrange for the purchase of the casket, when the body would be moved from the hospital morgue or mortuary to the funeral home to be prepared for public viewing and burial. They also will obtain the Death certificate from the City Council.

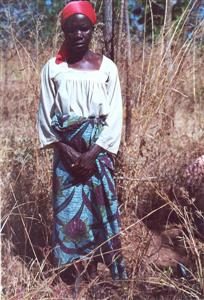

Women are expected to dress modestly when they attend a funeral or are in mourning. The women are expected to wear an old dress will a chitenje cloth wrapped around with tennis shoes, flip flops or pata pata. The hair may be uncombed and they are expected to hardly have any make up on. Wearing black is optional.

Men are expected to wear casual or old clothes too with worn out or well used shoes or sandals.

Typically among the urban middle class, burial takes place about the third day. The three days give enough time for most of the relatives travelling from remote areas to arrive in the town. On the day of burial the funeral procession or convoy of cars of mourners starts from the house to the funeral home. The mourners sing funeral songs all the time and majority weep and mourn. Large crowds gather at the funeral home and line up for body viewing of the open casket at the funeral home. Then the funeral procession goes to Church for a funeral service, and last to the cemetery for the burial.

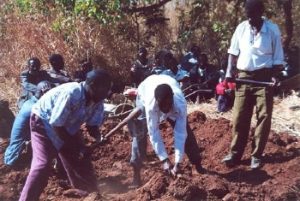

During the burial at the cemetery, men who are least close to the family of the deceased grab shovels and take care of the physical burial rituals at the grave site. They lower the casket into the grave. All close members of the deceased are asked to throw dirt or soil into the grave. A priest says last prayers, people will make some last minute comments about the deceased and some of the comments can be so funny and some very serious.

Crying and mourning aloud at this last point for departed loved one is expected as some relatives may get so out of control with grief, that other relatives physically restrain and console them.

The men then shovel the dirt into the grave and the grave is covered and a mound is created. Because some grave robbers will steal caskets and other valuables from fresh graves, some burials will pour wet cement around the casket to prevent possible theft.

After the burial is complete, most mourners disperse and go home. The closest relatives and friends are the only ones who return to the house of the deceased. The following morning, the house yard and the house are cleaned and swept. Some of the relatives leave but the closest people to the deceased relative are never left alone for almost two weeks. Some relatives stay with them to support, cook, feed them, and console them.

Funerals and Burials in the Rural Areas

When someone dies in the rural area among the Tumbuka of Eastern Zambia, the first thing is that there is very loud mourning, or chitengelo, by women in the village. The chitengelo is so unique that people who hear it night or day within a three mile radius immediately realize someone had died. Men messengers are immediately dispatched on foot and on bicycles to spread the bad news to all the surrounding villages. This has to be done immediately and quickly as burial has to happen the same day. Those people with cell phones in the village will call relatives in the cities and towns. But those relatives are not expected to attend the burial although they might travel to the village later.

Soon there are large crowds of people gathered around village hut corridors, chiwundo, in the village open spaces, and under trees. Children are always present during the funeral as they play the crucial roles of running errands for all mourners; known as kutumikila.

The body of the deceased is laid down in the middle of the floor of the hut and covere. Men and women mourners will enter and exit the hut as they arrive to mourn. Chickens, goats, pigs, and sometimes a cow is slaughtered to both feed the mourners and honor the dead person. Beer may also be provided if it happens to be available. Many relatives bring donations of food especially mealie-meal for cooking the nshima meal. The women immediately begin to draw water, cook, and prepare meals for the mourners.

Young men and elders carrying axes and hoes immediately go to the village burial ground. They determine where the dead person’s grave will be positioned and buried depending on where their relatives are already buried. Certain clans and families must be buried next to each other. This knowledge requires elders to be present who have knowledge of who was buried where in the past. The men dig the grave and get fiber from trees to make a ladder on which the body will be carried.

Late in the afternoon on the same day, the women wash the body and wrap it first in a blanket and then in a reed mat. If the family can afford, they may have a simple wooden coffin made of available wooden planks in the village. The body is then put on the ladder. About ten men lift the body on the ladder and hoist it on to their shoulders. The funeral procession will then slowly walk toward the burial site. There is loud mourning, wailing, and singing of funeral songs.

Once at the burial site, the large crowd of mourners sit on the grass and under trees. Women sit separate from men. Two men climb down into the grave to received the body and place it correctly. The close relatives throw soil or dirt into the grave. Then men use hoed to cover the grave until they create a mound. A Priest will say some prayers, relatives make comments about the deceased person. The mourners go back to the village. At the edge of the village coming back from the burial site, there are several containers of clean water. According to custom, all the mourners are supposed to wash off their feet all the red or yellow dirt from the grave site.

Soon after the burial which could be the next day, all the close relatives of the deceased perform the ritual known as kuphyera or to sweep. The homes and surrounding yards are swept. The people have their head shaved and they drink some traditional herbs. This is all meant to help the surviving heart-broken relatives to heal. <

About the Author

Mwizenge S. Tembo was born and grew up among the Tumbuka people of Eastern Zambia. He obtained his B. A. at University of Zambia, M. A. and Ph. D. at Michigan State University in 1987. He worked for ten years at University of Zambia before he came to Bridgewater College in Virginia where he teaches Sociology. He regularly writes magazine and academic articles, poems, and editorials. He is the author of the romance and adventure novel The Bridge: a Transoceanic Love Story; that he now effectively uses for teaching the Sociology of African contemporary culture. He is spearheading the building of a community Village Library Project at Nkhanga in Lundazi. He is Associate Prof. of Sociology at Bridgewater College.