Sharp Contrasts – July and August 1993 by Mwizenge S. Tembo, Ph. D.

Gruesome and horrendous stories and pictures of massacres of children, men, women, even priests continued to come out of Rwanda as of mid June 1994. This is a small Central African country with centuries old tribal animosities between minority Tutsis and majority Hutus that finally exploded into utter mayhem. It is estimated that more than half a million people may have been massacred in the senseless and barbaric battle of neighbor against neighbor.

At that same time meanwhile, about two thousand miles south of Rwanda, South Africa was ending more than three hundred years of oppressive minority White rule. There was jubilation with colorful ceremony and celebrations, as Nelson Mandela became the first Black president in a multiracial democratic South Africa. These glaring contrasts are some of the most enduring, mesmerizing, and yet confusing aspects of the vast continent of Africa which is more than three times the size of the United States, and yet has a population of only more than six hundred million, and has more than forty-eight countries.

There are powerful and graphic television images of disease, poverty, famine, war in Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, Mozambique and countless military coups and political turmoil on the African continent. Amidst all of this, it is sometimes downright impossible to see the small and the large changes, progress, adaptation, resilience and harmony that many ordinary Africans and the countries have maintained in the face of mind boggling political, economic and social obstacles over the last thirty years.

Zambia is perhaps one of those few African countries that have managed to spare themselves the political horrors and turmoil which have engulfed other African countries. The country is lucky but at the same has had leadership that continues to have some tremendous political savvy since the early 1960s. Zambia is a land locked African country, which has such neighbors as Angola, Zaire, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Malawi. It is the size of Texas and has a population of eight million people. It the second largest world’s producer of copper; second to Chile in South America. Since gaining political independence from British colonialism in 1964, Zambia has had civilian leadership and its own share of tumultuous political events. But nothing close to any massive tribal massacres, hatreds, famine, military coups characteristic of many African countries. Zambian political leaders often proudly state that the country does not have any of its citizens as refugees in neighboring countries.

First, this is a story of my exciting travel from Bridgewater College in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia last summer, to remote villages of Zambia to visit parents and relatives. Second, when my children’s teachers at John Wayland Elementary School heard that I was going to Zambia, they recruited me to contribute to the J-Bear Project. The John Wayland Elementary School was asking parents and others to carry the School Bear while travelling abroad to different cultures of the world. The photographs would later be used for world geography lessons for the students.

When the Zambia Airways Jumbo jet from London landed at the Lusaka International Airport on the African continent, I was filled with excitement. It was a crisp August morning. Peering through the windows, the brown grass of the dry season in Zambia was in sharp contrast with the plush green summer vegetation of the gorgeous Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, which I had left forty-eight hours before. The first change I noticed in the airport arrival lounge was that it was clean with rotating luggage carousals. It was a pleasant surprise. All of this did not exist five years before. The immigration officials looked young and were efficient. Within fifteen minutes, I was out of the airport arrival a lounge and meeting friends who had been waiting.

After almost twenty years of one party rule by the United National Independence Party (UNIP) with President Kenneth Kaunda as leader for thirty years, the Zambian economic conditions had deteriorated very badly by December 1989. Unemployment was more than twenty percent, inflation was running at more than a hundred percent, the black market for foreign currency and consumer commodities, and the accompanying corruption and inefficiency this breeds, made life miserable. This had all happened before November 1991 when Zambia held peaceful multiparty democratic elections. The UNIP administration was voted out of office by a landslide. Was Zambia going to be any different more than two years later? I was to find out.

As we drove from the Airport with my long time high school friend, I suddenly yelled. My friend slammed the brakes. I spotted something. We had just driven by a picture that I could have used a couple of months before when I published a magazine article, on mice as a traditional delicacy, among the people of the Eastern Province of Zambia. Young boys from a nearby shanty compound were carrying over fifty mice after digging them from the nearby fields. They were returning home to sell some at the market and to use the rest for the family’s dinner. They proudly obliged and posed for the pictures.

Contents [hide]

- 1 Capital City of Lusaka

- 2 AIDS in Zambia

- 3 July 31, 1993

- 4 August 1, 1993

- 5 August 3 – 4, 1993

- 6 August 7, 1993

- 7 Luangwa Game Park

- 8 August 19, 1993

- 9 About the Author

Capital City of Lusaka

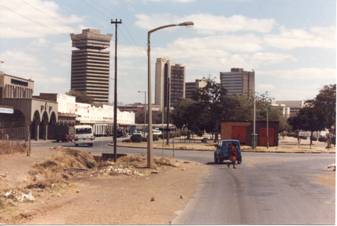

Zambia’s Capital City of Lusaka was as vibrant as ever with commerce at its highest peak. Too many people seemed to be selling something everywhere along the streets. But the city has really changed from the spacious, young, garden city of the late 1960s to the now crowded and clearly aging sprawling metropolis. On the outskirts of the city, residential units are sprouting at an incredible pace. Space that was mere bush barely five years ago is now covered with modest middle class income housing units. Driving along many roads of the city, several characteristics are striking. Lusaka is a walled city. Virtually all-residential dwellings and business establishments have ten-foot concrete walls with sharp glass or razor sharp barbed wire at the top. This is due to high rate of crime in urban areas. Many of the buildings down town need a good paint job. Trash could be picked up more.

But many of these decorative needs may pale in significance to the more immediate if not crucial needs of the people. In 1964, Zambia had a population of three million people. Today the country’s population has more than tripled to more than nine million people. Zambia has about forty-three percent urbanization rate, which is one of the highest in Africa. But the economy has hardly expanded to provide new jobs, housing, educational opportunities, health services, and transportation for the growing population, provide cheap affordable food for urban dwellers. This has created over crowding especially in shanty compounds in the fringes of the cities, crime, and severe strain on the health and sanitation services.

In spite of all the grim conditions and statistics, there is a silver lining in the cloud. Government controls are slowly being reduced by the new Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) government headed by President Chiluba. As a result of some of these measures, there is now a legal foreign currency exchange in the banking system and a much better supply of commodities such as sugar, cooking oil, bread, corn meal although the prices are very high. Instead of one or two government newspapers, there is now a more lively press with more than four newspapers.

AIDS in Zambia

Although it may be true that AIDS may have infected many heterosexual Zambians, there is now some evidence that contradicts the earlier alarming predictions particularly in the Western press. According to the New African Magazine in an article titled: “AIDS: the Epidemic that Never Was”, (New African, Dec. 1993) there is now evidence that the AIDS epidemic never did exist in Africa. Phillipe and Evelyne Krynen, sponsored by the French charity, Partage, now deny that the epidemic ever existed in the so called AIDS epicenter in Uganda. While the media, government public policy is driven by the international AID agencies to fight AIDS in Zambia, it is likely that people may be needlessly dying of curable and preventable diseases. For example, malaria, cholera, tuberculosis, malnutrition due to urban poverty and inadequate food, run of the mill venereal diseases, alcoholism and other forms of drug abuse and social discord.

My ten-day trip through towns and villages of the Eastern Province of Zambia provided further striking contrasts between urban and rural Africa. I started the more than four hundred-mile drive from the Zambia’s Capital City of Lusaka to the Lundazi rural small town at three in the morning on a Saturday.

July 31, 1993

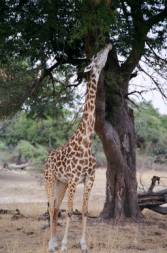

Driving in the dark in the two lane paved Great East Road was a challenge in itself. But what was more dangerous were some of the large potholes the paved road had sustained during the previous rainy season. But with the economic crunch that is common to virtually all African countries, the Zambian government may not have enough money to patch the roads promptly. A Dutch journalist had an anecdote after visiting Zambia briefly and returning to Europe. He was driving on the same Great East Road in broad day light when he noticed, in the middle of the road in the distance, what looked like a head of an animal. He slowed down and came to a halt. What he saw was the tip of giraffe’s head trapped in a pothole. This was of course a joke. Although the road was not really that bad, one had to be cautious to swerve around or slow down going over some of the larger potholes.

The Great East Road had been paved twenty-five years before when the country was in its more prosperous time. As dawn broke, dark human figures lurked on the road shoulders getting a head start on the rural daily chores. At seven A.M I was driving through the Muchinga Escarpment which is part of the Luangwa Valley. This had mountains that reminded me of the Blue-Ridge Mountains of the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. I stopped several times to get photographs and videos tapes of the valley and magnificent sunrise.

As one leaves the metropolitan areas of Africa into the countryside, life and time suddenly slow down and take on a different dimension. For example, just after the Luangwa Bridge that connects the Eastern Province to the rest of Zambia, a large truck, perhaps carrying two tons of corn had jack knifed and blocked the road on a sharp bend and steep slope. Traffic backed up half a mile as we all waited patiently as the truck driver and his two assistants and others tried to remove it. He maneuvered the truck back and forth inserting huge stone boulders under the shredding, spinning, burning, and smoking huge tires. I do not remember how long we waited because time suddenly was not that important. Here there were no tow trucks to call, no telephones, no fast food restaurants, no highway patrol cops, and there were no gas pumps a hundred miles either side of the road.

Before I arrived at my destination in Lundazi town at seven PM later that night, I had encountered cattle driven carts, people walking and often carrying bundles, cycling, and conducting commerce on the side of the road. Cows sometimes blocked the road. Pigs, chickens, and goats often darted across the road. I even stopped once for an hour to watch the Nyau and Muganda traditional dances at one of the villages.

August 1, 1993

I had spent a good night at the Lundazi town rest house or motel. There was a water crisis in the town because the town council was apparently waiting for a spare part they had ordered for one of the water pumps. As such water was only available only early in the morning or late at night. When the indoor plumbing was unusable, there were two out houses located outside the motel. I visited with my sister, her husband, and their children. Everyone was excited. The kids were overhead proudly telling their friends about their uncle who was from the city of Lusaka and had a car.

Later that day, I drove twenty miles on a dirt road to my village to visit my parents. Seven years before, I used to have to park the car and walk the last two miles to the village because there was no road and bridge on the creek just before the village. This time progress seems to have been made. Because government had to haul agricultural produce from the villages using trucks, a a make shift but barely usable road and bridge had to be finally built.

I was thoroughly pleased to see my mother and father. Over the next three hours, more than two dozen relatives shook my hand in the Zambian customary greeting of shaking hands and guests and host exchanging personal life status. This custom is known as malonje among the Tumbuka people of the Eastern Province of Zambia. To my surprise I discovered that this was no longer a village of mostly old illiterate citizens which had been the case twenty years earlier. When I pulled out ten newspapers, many of the young people began to read and discussed not only Zambian but also world politics including the election of Bill Clinton as the new US President. One of them, a thirty-year-old man had worked in the Zambia Army as an electronics signals caller. The majority of them were articulate high school graduates who had decided to return to the village because they could not get jobs or any type of training in the cities. A few village children were instructed to chase a chicken and catch it. I knew that was to be my dinner may be three hours later after my mother had dressed, roasted the bird in curry powder and vegetable oil cooked it for atleast an hour. Rural chickens are tough. Village life gives a more precise meaning to fresh food.

That night, my parents and I and now my two grown brothers and their wives sat around the fire like in old times. We talked and laughed late into the night catching up on as much news as possible.

August 3 – 4, 1993

For the J – Bear project, I traveled in the Lundazi district to several villages and a school and took photographs. People, especially children, were fascinated by the teddy bear and always very friendly and eager to pose for photographs with J – Bear.

August 7, 1993

This day left some of the most prominent memories from my trip. I woke up this morning in a motel in the town of Chipata, which is the provincial headquarters of the Eastern Province. About eighty miles west of Chipata lies the famous Luangwa National Park in the valley. In an impulsive and spontaneous fashion, I decided to drive to the magnificent game park that morning and spend a night there. I had this titillating irresistible imagination of the video images and still bright color photographs of elephants, giraffes, lions, wildebeest, monkeys, antelopes, hippos, antelope that I could take with me back to the United States as valuable mementos of my trip especially for my kids.

So I checked out of the motel, packed my belongings, filled up the gas tank and I was on my way. All this time I had been driving largely on the paved roads in the old beat up car. The road to the game park, however, was not paved. The first ten miles of the dirt road were relatively smooth and bearable. There were huge clouds of red dust behind me as I drove. Suddenly the road became very corrugated and the car began to shake, vibrate and bounce so badly that I could barely drive about fifteen miles per hour in certain spots. It was too late for me to turn back now. A few potholes here and there on the main paved Great East Road suddenly seemed like heaven compared to what I had gotten into.

The further I drove into the valley the hotter it became. I found six people, including two Scandinavian Europeans, stranded because the front wheel of their jeep had come off due to the violent bumps and vibrations. They had a toolbox but needed a spare part. I gave a ride to one of their passengers who had instructions to get the spare part and I dropped him twenty miles down the road by a road construction camp.

Luangwa Game Park

By noon I arrived in seething dry heat at Mfuwe tourist lodge in the Luangwa National Park. Small lone animals were every where I looked as most of them rested in the shade. I was hot but excited as I took a few pictures. The Mfuwe lodge was fully booked for that night. Why didn’t I try the Chichele lodge, which was only about fifteen miles away through the heart of the game park? The receptionist suggested. It sounded like a wonderful idea. I could see some game and take videos and photographs of wild animals on my way.

I drove slowly looking at animals and occasionally paused and took pictures through the car window. I saw zebras, antelopes, Thomson gazelles and an assortment of small animals all under tree shades resting. I saw a herd of buffalo under the shade of a large tree. After about half a mile, there was the dreadful sound of thud, thud, and thud. Oh No! I used a four letter word first in English and then in my native African tongue. I stopped the car and came out. Sure enough my front tire was flat right in the middle of the game park with a herd of mean looking dangerous Cape Buffaloes less than half a mile away. ‘A pride of hungry lions could be lurking just behind the bushes,’ I thought. I quickly glanced at the bushes on all sides around me expecting a curious or mad animal to suddenly charge out of the bush at me.

I could see the head lines: “Bridgewater Professor Stomped to death by Buffaloes”, “Zambian Resident in the US Eaten by Lions”, “Torso of a Zambian believed to be that of a Bridgewater Professor.” I remembered an American woman tourist who had been devoured by wild animals in an Eastern African Game a few years back. Her car had broken down in the middle of the game park and she had walked to try and get help.

I told myself not to panic. This should be a five-minute job. I checked my won out spare tire and fortunately it had air in it. How did I get into this stupid dangerous mess? I startled each time lizards rustled the dry leaves in the bushes, In this extremely nervous condition, I put on the car jack the wrong way the first time. I had to put the flat wheel back on and start over again. Within half an hour, sweating profusely and my heart just about ready to jump out of my throat, I changed the tire and quickly turned around.

Back at the lodge, they did not have any facilities for mending tubeless tires. The nearest garage or gas station where I could have the flat tire mended was eighty miles away back in the town of Chipata. I did not have a spare tire at all. If I had another flat, I could be stuck in the valley for a week. I had to return to Chipata right away. I was to drive carefully for four hours through eighty miles of rough bumpy terrain on a won out tire. Was I worried and anxious? At two thirty that afternoon, I began my risky return trip. Besides four bananas and some water, I had not eaten anything all day. Hunger was the least of my worries. The situation of driving on the won out tire was so much on my mind that it was almost driving me crazy. I needed someone, anyone to talk with to get my mind off the bad tire. A woman walking along the road and carrying a small bundle on her head waved me down. I stopped.

She rushed over and pleaded that she needed a ride, as she had to be in Chipata that day. She had already been walking for ten miles. I told her the grim reality. I did not have a spare tire. The one I had on was probably slowly losing air and could blow up any time. She and I could be stuck on the road in the wilderness of the valley for the night or even days. She did not mind the risk. She had a gravely ill grandfather admitted at the Chipata General Hospital whom she had to see.

After driving for a while, she said she was confident God would be with us because we would have a safe trip. As we conversed, my mind became at ease and I worried less. Three bumpy and dusty hours later, we arrived in Chipata. The bad tire had held up. I dropped her at the hospital and wished her good luck. She wanted to pay me for the equivalent of bus transportation. I declined the money. She really had no idea how much she owed me for just being there to talk to during those crucial moments. I immediately went to a gas station and bought a brand new tire and a tube.

August 19, 1993

After visiting both the rural and urban areas of Zambia, I flew back to the US. The rural inhabitants seemed to have a better quality of life. They looked physically healthier and happier. Urban dwellers on the streets in Lusaka seemed thinner. Maybe it is the cost of living or may be the stresses and anxiety of urban life including fear of crime, road accidents, high cost of living, frequent mysterious deaths and burials of work mates who died, supposedly of AIDS.