Nshima and Ndiwo: Zambian Staple Food

For ten million Zambians in a country the size of Texas or France in Southern Africa, the concept of “nshima” and what it stands for is the very basis of life. Nshima is the staple food eaten by not only Zambians but Malawians and many other African neighbors. Almost all indigenous African languages in Zambia probably call nshima by a different name according to the specific area language and dialect variation. The Chewa, Tumbuka, and Ngoni of Eastern Zambia and Malawi call it sima or nsima, the Bemba of Northern Zambia call it ubwali, the Tonga of Southern Zambia call it Insima and Lozi of Western Zambia call it Buhobe. A similar staple meal is called Sadza in Zimbabwe, Milli Pap in South Africa, Ugali is eaten in East Africa including in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, and Democratic Republic of the Congo. A similar staple meal called Fufu is eaten in West Africa particularly in Nigeria. Many Americans liken it to mashed potatoes or grits. But what exactly is this staple food eaten by perhaps an estimated 14 to 18 million people in Southern Africa alone?

For ten million Zambians in a country the size of Texas or France in Southern Africa, the concept of “nshima” and what it stands for is the very basis of life. Nshima is the staple food eaten by not only Zambians but Malawians and many other African neighbors. Almost all indigenous African languages in Zambia probably call nshima by a different name according to the specific area language and dialect variation. The Chewa, Tumbuka, and Ngoni of Eastern Zambia and Malawi call it sima or nsima, the Bemba of Northern Zambia call it ubwali, the Tonga of Southern Zambia call it Insima and Lozi of Western Zambia call it Buhobe. A similar staple meal is called Sadza in Zimbabwe, Milli Pap in South Africa, Ugali is eaten in East Africa including in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, and Democratic Republic of the Congo. A similar staple meal called Fufu is eaten in West Africa particularly in Nigeria. Many Americans liken it to mashed potatoes or grits. But what exactly is this staple food eaten by perhaps an estimated 14 to 18 million people in Southern Africa alone?

During the mid 1950s in a village among the Tumbuka in Eastern Zambia, an incident occurred that was to have legendary significance about the nshima staple food in the diet of the African peoples. It was during British colonialism in the rural district of Lundazi. A village Headman, a Mr. Kasaru, had been summoned from his village to see the European British District Commissioner. As common practice in rural Africa, people making a long journey on foot usually set off at dawn.

During the mid 1950s in a village among the Tumbuka in Eastern Zambia, an incident occurred that was to have legendary significance about the nshima staple food in the diet of the African peoples. It was during British colonialism in the rural district of Lundazi. A village Headman, a Mr. Kasaru, had been summoned from his village to see the European British District Commissioner. As common practice in rural Africa, people making a long journey on foot usually set off at dawn.

Headman Kasaru, is said to have set off at dawn with his wife insisting that he waits so that she cooks him and eats a good nshima meal to last him during the better part of the hot tiring day. The man insisted that he was going to be alright and that after all it was only a ten to fifteen mile walk. He was sure to arrive at the District Commissioner’s Office by ten that morning. Indeed, Mr. Kasaru had a brisk walk and the hot sun beat on him. But he arrived sweating, tired, terribly thirsty with patched lips at the District Commissioner’s Office that morning. The Commissioner would not see Headman Kasaru right away. He had to wait standing in line.

Observers said that Mr. Kasaru suddenly had a glazed look in his eyes and collapsed. His daughter-in-law, who happened to live nearby, splashed cold water on his face to revive him. Later after a good hearty nshima meal, village Headman Kasaru is said to have attributed all his problems to having refused to eat nshima before he left the village for his long journey that morning. The legend and saying that circulated in the whole area was: “Njara nkhamtengo, yikatonda a Kasaru.” which translates as “Hunger is as tough as a tree, Headman Kasaru succumbed to it.”

In the minds of the Tumbuka people, and indeed in the minds of the majority of Zambians, this particular incident vividly reaffirmed the significance of nshima in the lives and diet of the people. Nshima fills you up and offers people a bounty of energy to last a walk of a long distance, working in the fields, hunting animals, fetching mushrooms in the bush far away from the village. It is for this reason that folk tales, customs, rituals, gestures of hospitality and kindness or cruelty surround someone being offered nshima or denied the meal by their hosts.

What is Nshima and Who Eats It?

It is a food cooked from plain maize or corn meal or maize flour known as mealie-meal among Zambians. The price of corn meal and ultimately nshima, is a crucial matter in urban Zambian political and economic life. The government suddenly raising the price of corn meal sparked the political riots of June 1990 in the Zambian Capital City of Lusaka. The political crisis that ensued eventually let to multiparty democratic elections in Zambia in October 1991. The ruling party of United National Independence Party (UNIP) that had monopolized power for over 20 years was voted out of office. The Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) was voted into power by landslide.

Nshima has always been the basis of life in Zambia for as far back in history as people can remember. During the best of times the nshima meal is always eaten for lunch and dinner. This is the case during and after the harvest season in the villages in rural Zambia. This is from about April to November when the food reserves are generally adequate. During the lean months, “hunger period”, or what the Tumbuka call zinja, between December and March, the majority of rural people can often afford nshima only once per day during late afternoon.

Many of the urban dwellers, ranging from those in the low-income sector, the middle, and the affluent eat nshima during lunch and dinner. The poor, unemployed, and those in the urban shanty compounds often barely afford one meal of nshima once per day usually for dinner. What else do Zambians eat besides nshima?

Zambians are generally raised to believe that only nshima constitutes a full and complete meal. Any other foods eaten in between are regarded either as snacks or a temporary less filling or inadequate substitute or a mere appetizer. Lets say you meet a Zambian late in the afternoon and ask him if he or she has eaten. Most likely they will tell you that they haven’t eaten all day although they might have eaten a sandwich, peanuts, milk, and a few other non-nshima foods.

Nshima is such a key factor loaded with such emotional investment in the diet that many rituals, expectations, expressions, customs, beliefs, and songs have developed in the culture around working for, cooking, and eating of nshima. For example, nshima is best when eaten steaming hot. A Chewa speaking man in Eastern Zambia, in moments of great masculine exuberance might say:

“Ndine mwamuna ine, yikapola ndi ya mwana!” “I am a man who eats only hot nshima, if its cold I give it to children.”

There is a legend of an irate husband among the Chewa people of Eastern Zambia in the mid 1960s, who always admonished and insisted to his wife that the pot she was using for cooking nshima was not big enough. He wanted her to abandon the pot and use an even bigger one. The woman sung the following song:

Yacepa yacepa sefuliya

Yacepa yacepa sefuliya

Bamuna aba

Acita uluma a a ha! ha! ha! ngati mkango

This pot is small

This pot is small

My Husband

He roars Haa!! Haa!! Haa!!

Like a lion

The famous observation that while Europeans might have one or two terms for describing snow and Eskimos might have more than 15 also applies to Zambian description of nshima. There are anywhere from 10 up to 20 terms depicting various types and states of nshima. The good or perfect nshima, if cooked from corn meal, is one which is steaming hot, snow white, smooth, not too soft or too hard, and served promptly on clean beautiful dishes. The good or near perfect second perhaps more important half of the meal, the relish or ndiwo, must be well-cooked meat, fish, or poultry with delicious well-seasoned gravy or what is called soup among Zambians.

Nshima Recipe

Nshima is the staple food for 10 million Zambians. It is eaten at least twice per day; for lunch and dinner. Another second dish, known as ndiwo, umunani, dende or relish, must always accompany nshima. The relish is always a deliciously cooked vegetable, meat, fish, or poultry dish. By comparison to other cultures, Zambian recipes tend to be bland and hardly use any hot spices at all. However, they use other traditional ingredients and spices that give Zambian foods that distinctive unique taste and flavor.

4 Cups Water

2 Cups plain corn meal

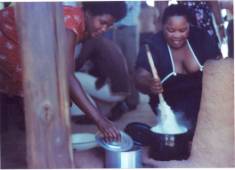

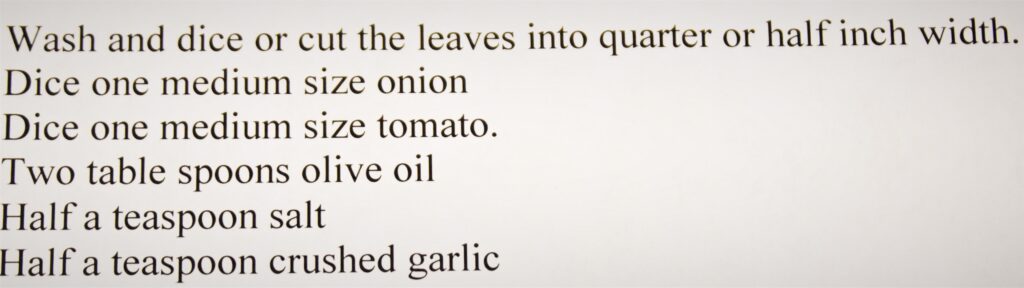

Method: Pour 4 cups of water into a medium size cooking pot. Heat the water for 3 – 4 minutes or until lukewarm. Using one tablespoonful at a time, slowly sprinkle 3/4 cup of the corn meal into the pot while stirring continuously with a cooking stick. Keep stirring slowly until the mixture begins to thicken and boil. Turn the heat to medium, cover the pot, and let simmer for 3 to 5 minutes.

Cautiously remove the top. Slowly, a little at a time, pour into the pot 1 and a quarter cups of corn meal and briskly stir with the cooking stick until smooth and thick. Stir vigorosly. Sprinkle a little more corn meal and stir if you desire the nshima to be thicker or less if you want softer nshima. Cover, turn the heat off and let nshima sit on the stove for another 2 to 3 minutes. Serves 4 people.

Must always be served hot with a vegetable, bean, meat or fish dish or ndiwo.

The Ndiwo Dish

One of the most significant aspects of the Zambian staple meal by which the nshima is ultimately identified with what in English might be called the “relish”. The relish is an English somewhat poor equivalent or translation, which obviously, does not precisely reflect or capture what Zambians often realize is the very fundamental and transcending essence of the dish. The relish is a second dish that is always and without exception served with the nshima. It has many indigenous equivalent names. Among the Tumbuka of Eastern Zambia it is known as dende, among the Ngoni and Chewa of Malawi and Eastern Zambia it is known as ndiyo or ndiwo, and umunani among the Bemba speaking people of Northern Zambia and the Copperbelt Province.

One of the most significant aspects of the Zambian staple meal by which the nshima is ultimately identified with what in English might be called the “relish”. The relish is an English somewhat poor equivalent or translation, which obviously, does not precisely reflect or capture what Zambians often realize is the very fundamental and transcending essence of the dish. The relish is a second dish that is always and without exception served with the nshima. It has many indigenous equivalent names. Among the Tumbuka of Eastern Zambia it is known as dende, among the Ngoni and Chewa of Malawi and Eastern Zambia it is known as ndiyo or ndiwo, and umunani among the Bemba speaking people of Northern Zambia and the Copperbelt Province.

The ndiwo second dish which is always served with nshima is often cooked from domestic and wild meats that include beef, goat, mutton, deer, buffalo, elephant, warthog, wild pig, mice, rabbits or hare, antelope, turtle, alligator or crocodile, monkey, chicken eggs. Green vegetables include domestic or garden grown like collard greens, known as rape in Zambia, cabbage, pumpkin and squash leaves, pea leaves, cassava leaves, bean leaves, kabata, nyazongwe, or bilozongwe leaves. There are numerous wild green vegetables that include katambalala, chekwechekwe, katate, lumanda, and numerous others, which are all, referred to by the very well known generic name of delele or thelele among people of Eastern Zambia and Malawi. There are anywhere from 20 to 30 of this group of thelele vegetables.

The ndiwo second dish which is always served with nshima is often cooked from domestic and wild meats that include beef, goat, mutton, deer, buffalo, elephant, warthog, wild pig, mice, rabbits or hare, antelope, turtle, alligator or crocodile, monkey, chicken eggs. Green vegetables include domestic or garden grown like collard greens, known as rape in Zambia, cabbage, pumpkin and squash leaves, pea leaves, cassava leaves, bean leaves, kabata, nyazongwe, or bilozongwe leaves. There are numerous wild green vegetables that include katambalala, chekwechekwe, katate, lumanda, and numerous others, which are all, referred to by the very well known generic name of delele or thelele among people of Eastern Zambia and Malawi. There are anywhere from 20 to 30 of this group of thelele vegetables.

Because the delele and other groups of vegetables are always so plentiful and easily available in the natural environment, it is one ndiwo that is frequently held in contempt. In rural Zambia the daily conversation will often focus on how difficult it is to get ndiwo. Someone will invariably complain that they have been eating delele for three straight days. Since any type of meat protein is the most scarce, it is the most valued or desired. Infact there is a special term that is used for that irresistible desire or yearning for meat which is known as nkhuli in Eastern Zambia and Malawi.

Because the delele and other groups of vegetables are always so plentiful and easily available in the natural environment, it is one ndiwo that is frequently held in contempt. In rural Zambia the daily conversation will often focus on how difficult it is to get ndiwo. Someone will invariably complain that they have been eating delele for three straight days. Since any type of meat protein is the most scarce, it is the most valued or desired. Infact there is a special term that is used for that irresistible desire or yearning for meat which is known as nkhuli in Eastern Zambia and Malawi.

The pair of nshima and dende or ndiwo is therefore the most significant Zambian meal. One is rarely possible without the other. The two are like siamese twins, the left and the right hand, student and teacher, husband and wife, male and female or mitt and glove in American baseball parlance. Having one without the other is possible but is always regarded as a serious anomaly or oddity. If the cook induces the condition of eating nshima or ndiwo on its own, it would be regarded as lack of proper planning. If the diners induce the condition, they would be regarded as having poor judgement or being immature.

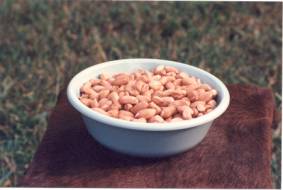

Other types of ndiwo or dende include fish, peanuts, peanut butter (chibwabwa or chimphonde), numerous types of wild mushrooms, and many varieties of beans and peas.

One excellent reason for why nshima and ndiwo always go together is that they complement each other. Nshima eaten by itself is rather relatively plain and bland. Although if you are an experienced, seasoned, and traditional eater of the meal, the nshima has its own subtle differences in taste and flavor depending on the type of mealie-meal and how it was cooked. In fact when Westerners who visit Zambia first eat nshima their typical reaction is: “God, why don’t you add butter, sugar or something to give it some taste or flavor?” But that is exactly the beauty and deeply acquired taste and appreciation of nshima in that it is the dende, ndiwo or relish second dish that gives it the unique taste or deliciousness. The nshima therefore accentuates the ndiwo and the reverse is also true. Eating the nshima by itself will fill the eater but without any taste ecstasy. Eating the ndiwo by itself might be gratifying but the individual will not feel full or satiated. Eating nshima by itself is known as kusoza among the Tumbuka people of Zambia. Kusinkha refers to eating ndiwo or relish by itself.

Types of Nshima

In traditional village Zambia, nshima has many types and states. There is nshima that is cooked from cassava meal (sima ya chikhau or chinangwa), sorghum meal (sima ya chidomba), finger millet meal (sima ya kambala). Potentially nshima can be cooked from any grain and tubers that can be transformed into meal or flour. There is nshima that has lumps in it (sima ya mambontho). This nshima is often the result of hasty cooking and only young inexperienced girls, men, and novices are expected to make this mistake.

There is nshima yopola. This is nshima that has gotten luke warm to cold because either it was cooked too early or eaters, guests, or diners delayed in getting to the table. This nshima is rather hard and might even crumble as the eater tries to get a lump. There is nshima ya cimbala. This is nshima left over from the previous night. It is usually stone cold and wet from steam condensation over night. Children are the only ones expected to eat this type of nshima sometimes for breakfast. Adult men are not advised to eat nshima ya cimbala as it is believed to cause weakness in the joints and also likely to usurp a man’s sexual energy.

Nshima yibisi means raw nshima. This is the nshima that was badly and hastily cooked perhaps with a very weak flame due to inadequate firewood or impatience on the part of the woman or the cook. One extreme way of testing if the nshima is raw is to push one’s middle finger deep into the just cooked nshima on a plate like one would push a dip stick when determing oil level in an automobile engine. If the nshima is well cooked, the finger will hardly penetrate, as it will be too hot for the tester. But if the nshima is under cooked, the finger will penetrate all the way and the individual tester will hardly feel any discomfort.

There is nshima ya mgayiwa. This is nshima that is cooked from corn or maize that is not hand processed. It is corn meal ground directly from corn using a hammer mill. This type of nshima is darker and very coarse or rough. Many Zambians will only eat this as a sign of hardship, in an emergency, or if they are in institutions like the boarding school, armed forces, or prison. In extreme cases it might cause diarrhea because of too much roughage for those not accustomed to eating it.

There is nshima ya kambandila which is cooked from maize or corn meal that is made from corn that has hardly dried in the fields just before harvest. This is also often done in desperation as the family might have run out of corn from the previous season’s harvest.

Nshima yosoza refers to eating the nshima without the second dish; the relish. This again is an extreme tremendous sign of suffering if individuals have to resort to eating nshima without relish. This extreme case is rare as in most cases individuals who eat nshima yo soza are said to be careless. There is a learnt skill in eating a large plate of nshima matched with often a smaller potion or serving of relish. One has to learn to match the rate of eating the nshima with the specific served portion of the relish. Going to the relish pot for some more is usually unacceptable or impractical. So in the unfortunate situation of mis matching the rate of eating nshima and the relish, the individual might end up eating nshima yo soza.

Nshima features very prominently in many other cultural aspects of the community. For example, a traditional healer will often prescribe that a patient gets the herb soaked from roots of a certain tree and use it for cooking nshima. The patient has to eat this type of nshima for two to three weeks to a month. This is true for a child who is being treated for childhood epilepsy or seizures for example. This type of nshima is known among the Tumbuka people as kasima ka mnkhwala or a tinny nshima cooked for medicinal purposes.

Balanced Nutrition and Eating Habits

The perception and eating customs of nshima among rural and urban people sometimes differ. Rural people are very frugal in the way they eat nshima. They prefer to eat nshima with only one ndiwo or relish dish at each meal. This is out of necessity as cooking one ndiwo for the two meals everyday is very demanding on the time of virtually all mothers or wives in rural villages. Cooking multiple ndiwos is therefore often impractical. Urban educated middle and upper income people however regard eating multiple relishes during each nshima meal as one of the principle demands of proper nutrition and prestige. This is usually nshima with at least one vegetable and one meat or fish relish. This contrast in attitude and customs was demonstrated one day during research fieldwork in a conversation with a middle-aged man in a village in the Lundazi rural district of Eastern Zambia. Asked whether he would appreciate and enjoy a meal of nshima with several ndiwos of beans, meat, and vegetables, his vehement and puzzled reply was:

“Yayi! Uku nkhwananga dende.”

“No! Why waste so much relish on one meal?”

In other words, his reply was that it was being wasteful and rather extravagant to eat nshima with more than one ndiwo during one nshima meal. Those ndiwos would serve a better and more economic purpose by eating each one of them during separate nshima meals.

The Making of the Corn Meal or Mealie-Meal for Nshima

The traditional making of the maize or corn meal is very demanding and labor intensive. The proliferation of diesel run hammer mills has helped in relieving many of the rural Zambian women. The aim of the whole process is to make very white corn meal that will cook a very white smooth to the taste nshima. Depending on the urgency and planning habits of the individual woman, the whole process might take anywhere from three to ten days. Most women will start the process of making new corn meal when there is about a week’s supply of corn meal left in the house.

The process starts with the woman retrieving dry corn on the cob, which had been stored safely after harvest in a structure known as nkhokwe among people of Eastern Zambia and Malawi. The woman will elicit the help of children, aunts, female relatives and close friends in the village and in many cases men to remove the corn from the cob the process known as kugumuza.

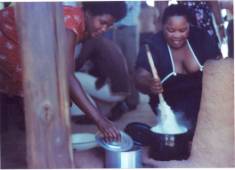

The girls and women then pound the corn in pestles and mortars to remove the husks. Although this is a physically demanding task, the work is easier by making it communal when ever possible. Song is also used during the pounding, which can often be heard three to four miles away. In some cases, all the women in the village will arrange to pound the maize for their households at the same time. They agree to wake up at 3 a.m to begin pounding the corn together while they sing. The work would then be completed by mid day. There are numerous pounding songs, in all villages of rural Zambia, like this popular one among the Tumbuka of Eastern Zambia.

Leader: Amama Ae – e – e – e ! ! !

All Women:

Ine Amama nkhuwela ! ! !

Nabanangilaci ine analume aba

Ine Amama nkhuwela

Vitolanenge waka viminkhwele pera

Chikhumbo namtima ine nkhawele

Leader: My mother Ae – e – e ! ! !

All Women:

Mother I’m coming back home from my marriage

What have I done to offend my husband?

Mother I’m coming home from my marriage

Let monkeys marry one another

The Heart grows fonder I’m coming home

The songs composed by the women are often a social commentary on the goings on in the community and for expressing any stress and tension in marital and other social relationships in the community. In this song, the woman is threatening saying she is going to go home to her mother leaving the marriage. She is lamenting why she ever got married to her husband. She is mocking him that if he goes on to marry a second wife then “let monkeys” marry one another. Although the heart grows fonder because of love, she is still going to return to her mother.

The songs composed by the women are often a social commentary on the goings on in the community and for expressing any stress and tension in marital and other social relationships in the community. In this song, the woman is threatening saying she is going to go home to her mother leaving the marriage. She is lamenting why she ever got married to her husband. She is mocking him that if he goes on to marry a second wife then “let monkeys” marry one another. Although the heart grows fonder because of love, she is still going to return to her mother.

After the husks have been removed from the corn, the corn is no longer called by its usual name of vingoma (maize) but mphale. The mphale-processed corn is then soaked in water for at least three days. During this period, the mphale becomes soft and the water in which it is soaking has a sour taste due to fermentation. The sour liquid, known as mteteka has an additional use. It is often used to cook sour porridge with peanut powder for what amounts to a delicious breakfast that is tangy and stimulates one’s taste buds. The various ways and ingredients for cooking porridge for breakfast are discussed elsewhere.

After soaking for three days, the mphale processed corn is removed, thoroughly washed in clean water, and spread on special large mats (mphasa) in the sun to dry. During the drying process, young children and in may cases women themselves have to watch, continuously guard, and shoo away village goats, chickens, pigs, cows, insects, and wild birds. After the mphale-processed corn is relatively dry, the women in rural Zambia to day have two choices for turning the corn into meal or flour. First, they could pound the corn into meal in mortars with pestles.

After soaking for three days, the mphale processed corn is removed, thoroughly washed in clean water, and spread on special large mats (mphasa) in the sun to dry. During the drying process, young children and in may cases women themselves have to watch, continuously guard, and shoo away village goats, chickens, pigs, cows, insects, and wild birds. After the mphale-processed corn is relatively dry, the women in rural Zambia to day have two choices for turning the corn into meal or flour. First, they could pound the corn into meal in mortars with pestles.

Second, the women could obtain some money. They could carry the mphale-processed corn on their heads for sometimes a three to six mile round trip to a hammer mill. Bicycles are sometimes used if available. The corn is then grounded into mealie-meal for a fee using a diesel driven hammer mill. Once the corn meal is made, it is again spread on the large special mats (mphasa) in the sun to dry. These mats might be as large as twelve feet long and eight feet wide. After this, the white corn meal is stored away ready for use for cooking the nshima meal.

Second, the women could obtain some money. They could carry the mphale-processed corn on their heads for sometimes a three to six mile round trip to a hammer mill. Bicycles are sometimes used if available. The corn is then grounded into mealie-meal for a fee using a diesel driven hammer mill. Once the corn meal is made, it is again spread on the large special mats (mphasa) in the sun to dry. These mats might be as large as twelve feet long and eight feet wide. After this, the white corn meal is stored away ready for use for cooking the nshima meal.

The Role of a Good Wife and Mother and Ndiwo

Finding different types of ndiwo or relish for each day’s meals is one of the most demanding and challenging tasks for all mothers and housewives in Zambia. The responsibility stretches every woman’s creativity virtually everyday. There are two extremes in the choice of ndiwo by the woman. A woman who is poor at it might cook one type of relish and serve it to her family for two straight days. The ndiwo gets boring or kutinkha and family members will not enjoy the nshima meals. The condition of eating the same type ndiwo with nshima for more than four consecutive meals and feeling bored with it is known as kutinkha. This is every mother and wife’s nightmare. This happens even with the most delicious ndiwo like poultry, fresh mushrooms, or meat.

A woman who is good and creative with finding ndiwo will cook one type one day and a different one the following day. For example, the ndiwo for one day might be a delele green vegetable, the following day it might be fire dried beef from two months ago, the following day she might cook beans. In this way, her husband and entire family will enjoy their nshima meals tremendously.

How the Ndiwo Dish is Cooked

There are three basic methods of cooking relish or ndiwo in the Zambian traditional cuisine. All fresh meats and fish are generally boiled in plain water until soft and salted. If available, onions, tomatoes, and vegetable oil might be added which improves the taste of the meat especially the gravy in which the nshima lump is always dipped during meals. Since most of the meat and poultry from both domestic and wild animals is natural, it is very lean with virtually no fat and has a very strong aroma.

Second, some genres of ndiwos or relish like mice, termite ants, caterpillars, and certain birds like baby doves (vibunda) are strictly roasted and fire dried. There is no other way in which they are customarily cooked.

The third and perhaps most unique but common method of cooking ndiwo in traditional villages of especially Eastern Zambia and Northern Malawi is that of cooking with chidulo and kutendela. If there is any cooking recipe besides nshima that so deeply pervades the entire diet among rural Zambian people it is chidulo and kutendela. This is so perhaps because the two methods make some of the many wild foods so tender, delicious and edible.

Chidulo is an ingredient that is used for cooking virtually all wild and some garden variety dark green leaf vegetables and wild mushrooms. The chidulo liquid is made from burning dry banana leaves, peanut leaves, or pea leaves, bean stalks and leaves or dry maize stalks and leaves. If the chidulo was being made from dry maize stalks and leaves, the woman who wants to cook wild or garden dark green leaf vegetables will collect a pile of dry stalks. She will then torch and let them burn completely. She will collect the cool ashes and put them in an old container with holes at the bottom. The container could be an old gourd or pot. Plain cold water up to a gallon will be slowly poured into the ashes. The water soaks into the ashes, drains through and collects into a container inserted at the bottom of the ash container. The process is known as kucheza. The liquid, known as chidulo, that is collected has a light yellow color and tastes like vinegar.

Chidulo is an ingredient that is used for cooking virtually all wild and some garden variety dark green leaf vegetables and wild mushrooms. The chidulo liquid is made from burning dry banana leaves, peanut leaves, or pea leaves, bean stalks and leaves or dry maize stalks and leaves. If the chidulo was being made from dry maize stalks and leaves, the woman who wants to cook wild or garden dark green leaf vegetables will collect a pile of dry stalks. She will then torch and let them burn completely. She will collect the cool ashes and put them in an old container with holes at the bottom. The container could be an old gourd or pot. Plain cold water up to a gallon will be slowly poured into the ashes. The water soaks into the ashes, drains through and collects into a container inserted at the bottom of the ash container. The process is known as kucheza. The liquid, known as chidulo, that is collected has a light yellow color and tastes like vinegar.

This is the liquid in which the wild vegetable will be cooked. Apart from the unique sought after vinegary taste it gives the vegetables, the chidulo has another perhaps more important function of softening the other wise tough and course wild greens. If many of the wild greens like cassava leaves, collard greens, kabata and many others were simply boiled in plain water, they would never be edible, tender or taste so delicious. The chidulo has other additional advantages. When anybody is ill with throat sores, they are offered delele cooked with chidulo. The salty vinegary taste helps heal throat sores faster.

This is the liquid in which the wild vegetable will be cooked. Apart from the unique sought after vinegary taste it gives the vegetables, the chidulo has another perhaps more important function of softening the other wise tough and course wild greens. If many of the wild greens like cassava leaves, collard greens, kabata and many others were simply boiled in plain water, they would never be edible, tender or taste so delicious. The chidulo has other additional advantages. When anybody is ill with throat sores, they are offered delele cooked with chidulo. The salty vinegary taste helps heal throat sores faster.

Cooking green leaf vegetables in chidulo alone in never adequate. There must be the additional process of kutendela. This is adding peanut powder to the vegetables. The addition of peanut powder to vegetables is highly valued and appreciated as it adds flavor, a unique taste, and a nice aroma to the vegetable relish.

The peanut powder, used for cooking kutendela vegetables, have to be made afresh each time a woman cooks. The woman starts by getting dry raw peanuts stored away in the shell in a special dry structure known as chilulu. The raw peanuts are shelled and put in a mortar. They are pounded for a few minutes using a pestle. The pounded peanuts are taken out and sifted for fine particles of crushed peanuts to be separated and removed. The more solid particles are returned to the mortar and pounded once again. This process is repeated until enough fine peanut powder or nthendelo among the Tumbuka, is collected to cook the vegetables with. The recipe for cooking vegetable with chidulo and kutendela is as follows:

RELISH OR NDIWO RECIPE

Collard or Rape Green Leaves with Peanut Powder

7 Cups or 1 lb. chopped collard greens

1 Large size chopped tomato

1 and a half Cups raw peanut powder

2 Cups water

1/2 Teaspoonful Arm and Hammer Pure Baking Soda or 1 Cup Chidulo

1/4 Teaspoonful salt

Method: Pour 1 cup of water into medium size cooking pot. Add half a teaspoon of pure baking soda and stir until thoroughly dissolved. Place pot on burner on medium heat. Add 7 cups of chopped collard greens and the 1 chopped tomato. Cook on medium to high heat for 5 to 8 minutes. Add 1 and a half cups raw peanut powder, 1/4 teaspoon salt, and 1 cup of water. Stir thoroughly and lower the heat to below medium. Cover and simmer for 15 to 20 minutes stirring every 2 to 3 minutes to prevent bottom from burning.

Serve hot with nshima

Serves 4 people

This is the most basic and popular recipe in Zambian traditional cooking as it is used for cooking the majority of the many green leaf vegetables including squash or pumpkin leaves, bean and pea leaves, cassava leaves, and wild mushrooms.

This is the most basic and popular recipe in Zambian traditional cooking as it is used for cooking the majority of the many green leaf vegetables including squash or pumpkin leaves, bean and pea leaves, cassava leaves, and wild mushrooms.

The peanut powder has multiple uses in the cooking of many traditional Zambian foods. Bala lotendela is porridge cooked with peanut powder. Mpunga wotendela is rice cooked with peanut powder.

Mthiko is the cooking stick that is specially made for cooking nshima and ndiwo. The significance of the mthiko cooking stick is reflected in the beliefs and customs of the people. Men and boys are traditionally prohibited from using or eating off of the stick. The masculinity of men and that of boys of puberty age is believed to be compromised if they use the cooking stick in this manner. A woman’s femininity is often also measured, among other criteria, by how well she cooks or ‘handles the mthiko cooking stick’.

All of this requires tremendous skill and effort on the part of the woman. She has to know a good source of chidulo liquid, how long to cook the greens or mushrooms, when to add peanut powder and how often to stir the cooking ndiwo or relish. All Zambian women who grew up in a traditional home, particularly in the rural areas, acquire these skills during their childhood.

Although there have been remarkable changes in the customs surrounding how the nshima and ndiwo meal is served, there are certain basic traditional practices that have remained constant.

Once the woman has finished cooking the nshima, she serves it according to the number, ages, and types of people partaking in the meal. Children under the age of eight will eat with their mother and other female kin. The father, other males and boys over eight years old are served and eat separately. The pair of nshima and ndiwo, drinking water and basin of clean water are placed in the middle. The dinners sit around the meal making a circle. The oldest person washes their hands first and the youngest last. In cases where the nshima is served in covered dishes, the oldest person must always uncover the nshima and ndiwo first.

Zambian Nshima Eating Manners, Customs, or Etiquette

The diners sit around the table or if sitting on the floor, they make a circle around the nshima. Zambians traditionally use bare hands when eating nshima. From time immemorial up to 2004, the custom was that all the diners first washed their hands from a dish of clean water. This custom has been changed in the entire society. A directive was apparently given from the Ministry of Health that due to reasons of maintaining better hygiene, the new custom of “D-Washa” was introduced. The new or modified custom is that the guests, elders, older adults, younger people and children wash their hands in that order. The youngest person or the host, will pour water from a pitcher or water jug so that a diner will wash both their hands thoroughly with soap and let the dirty water drop or collect in a dish. The same procedure is followed once the meal is completed. The dirty water is discarded either in between or at the end the end of the meal depending on whether the water is moderately or very dirty looking.

The diners sit around the table or if sitting on the floor, they make a circle around the nshima. Zambians traditionally use bare hands when eating nshima. From time immemorial up to 2004, the custom was that all the diners first washed their hands from a dish of clean water. This custom has been changed in the entire society. A directive was apparently given from the Ministry of Health that due to reasons of maintaining better hygiene, the new custom of “D-Washa” was introduced. The new or modified custom is that the guests, elders, older adults, younger people and children wash their hands in that order. The youngest person or the host, will pour water from a pitcher or water jug so that a diner will wash both their hands thoroughly with soap and let the dirty water drop or collect in a dish. The same procedure is followed once the meal is completed. The dirty water is discarded either in between or at the end the end of the meal depending on whether the water is moderately or very dirty looking.

It is considered rude for a young person to wash their hands first before the adults, older siblings, and guests have done so. Young people help to serve the adults and guests at the table to wash their hands pouring the water from a pitcher while each dinner washes their hands. A younger person or child should not stop eating and wash hands first, let alone leave the dining table, before adults do. However, if an adult sees a younger person or guest who has obviously stopped eating because they are full, the adults or the host will graciously grant “permission” to the waiting person to wash their hands. It is considered good customary behavior for everyone to wait seated at the table until everyone has finished eating and washed their hands.

It is considered rude for a young person to wash their hands first before the adults, older siblings, and guests have done so. Young people help to serve the adults and guests at the table to wash their hands pouring the water from a pitcher while each dinner washes their hands. A younger person or child should not stop eating and wash hands first, let alone leave the dining table, before adults do. However, if an adult sees a younger person or guest who has obviously stopped eating because they are full, the adults or the host will graciously grant “permission” to the waiting person to wash their hands. It is considered good customary behavior for everyone to wait seated at the table until everyone has finished eating and washed their hands.

Eating is always with only the one right hand. Both hands are never used when eating nshima. Only small children and perhaps strangers unfamiliar with the culture will use both hands at the same time when eating nshima. Westerners and other foreign visitors will be given forks and knives if the host notices that the guest is facing difficulties as fresh cooked nshima is always sizzling hot. One hand only is always used when eating nshima. The right hand only for the right handed individual and left hand only for the left handed person.

The customary procedure is to cut a good size lump of nshima and slowly shape it into a smooth round ball using the palm and fingers of the one hand. The nshima is then dipped into the second dish, the ndiwo, before it is eaten. All of this is often done in a relaxed deliberate way while the diners hold casual conversation. The older person is always the one to stop eating first when satisfied. He or she must leave a portion of the nshima for the younger persons and children to finish off or take to the kitchen when clearing dishes. The oldest person will wash their hands first.

It is considered very dignified and enjoyable to eat nshima slowly while making and smoothening the lump carefully before eating it; making good casual and relaxed conversation in the process. Young people eat and listen and can participate in the conversation when asked a question. But generally a well-behaved young person is expected to listen and gain wisdom from the elders during these meal times.

Zambians ordinarily will not ask you if you want to eat something especially if you are visiting a home. The educated elite and the well off might ask if you want to eat or drink something and might give you a variety of choices. But generally a host family will offer you snacks like tea, soft drinks, beer and even a main meal of nshima; the Zambian staple meal, without asking for your permission. Traditionally, it is considered rude and perhaps even selfish and cruel if you ask your guests: “Are you hungry and should we cook nshima for you?” According to custom, a guest who might be really hungry will say “No” out of shyness and embarrassment and they will then be expected to leave. It is assumed that as long as you are staying and having conversation, its considered courteous to offer you anything that the family may have for you to eat. Refusing to eat completely is considered rude unless you are close acquaintances or good friends with your hosts. Even if you are full, you can always eat a little. This is considered polite.

Common Nshima Dos and Don’ts

There are several key dos and don’ts about customs surrounding how the nshima is traditionally served and eaten among Zambians.

*Do not serve left over nshima from a previous meal to any adult.

*When eating, a younger person should never stop eating and begin washing hands first unless permitted by the older person.

*Guests who suddenly arrive when you are eating should always be invited to join in sharing the meal.

*A lone guest should never be served the meal alone. Another person, often a young reliable child, should always eat the nshima with the guest.

Nshima with ndiwo is the most important meal. It is so important and embedded in the traditional culture of the people that it features very prominently in the languages, expressions, tales of hospitality and wisdom and folk tales.

A guest will say the hosts are very kind and generous if they cook him nshima with very delicious ndiwo which may be chicken, beef, goat, or many other types of ndiwos. A young man courting a young woman will think highly of her if she cooks and serves him nshima with delicious ndiwo especially chicken.

In traditional Zambian folk tales, Kalulu the hare is the celebrated trickster. In many folk tales, Kalulu the hare will visit lion who will cook him nshima with delicious chicken. A typical story is like the following from a reader which is a compilation of Zambian folk tales from Eastern Zambia.

KALULU THE RABBIT FOOLS THE DOCTOR

The Lion had a reputation all over the earth that he was a good doctor. The Lion had all kinds of medicines to treat all kinds of illness.

One day, the Lion received word that the Leopard was stabbed and injured by a wild pig while hunting it. When he heard this word, the Lion called the Zebra and said:

“Friend, the Leopard is sick. Would you like to come with me and visit him?

The Zebra agreed and said:

“Yes king, I will come with you. ”

So, the Zebra carried the Lion’s baggage.

Before they could walk very far, the Lion stopped and said to the Zebra:

“Look here my friend. You should remember this wild ndiwo green vegetable when we arrive at the Leopard’s home. When the Leopard gives us meat, you should come here and get this relish.”

The Lion pointed out the type of wild vegetable to the Zebra. After they had walked for some distance, the Lion stopped again and said:

“Look here friend, when the Leopard cooks us any food, come here and collect that ndiwo vegetable over there.” The Lion again showed the Zebra the type of ndiwo. When they arrived at the Leopard’s house, the Lion rubbed his medicine on the Leopard’s body. Soon afterwards the Leopard was healed.

The Leopard then gave wild pig meat to the Lion and said:

“King, this is yours. Eat it.”

The Lion then told the Zebra:

“Look, friend, we cannot eat this meat unless we have some extra ndiwo. Would you go and get some of that ndiwo vegetable I showed you on the way when we were coming.”

Without delay, the Zebra ran to go and fetch the ndiwo.

When the Zebra returned, he found that the Lion had already eaten all the meat. The Zebra slept hungry. The following morning, the Leopard cooked them a nice nshima meal again. The Lion played his trick again. He sent the Zebra to go and collect the same vegetable from the bush. While the Zebra was away, the Lion again ate all the food. When they both returned home, the Lion was very fat from eating all the good food while the Zebra was very thin because of hunger.

After several days, the Elephant fell sick. So he summoned the Lion for help. The Zebra refused to go. Therefore the Lion had no one to carry the baggage for him. When the Lion saw Kalulu the Rabbit walking along the road, the called him and said:

“Kalulu, come here! You walk around all day stealing other people’s things. Come on! Let’s go. You can carry my baggage.”

Kalulu the Rabbit quickly agreed and said:

“King, put the baggage on my head. Laziness is really a bad thing.”

The Lion and Kalulu walked away together. On the way, the Lion stopped and said:

“Look Kalulu, when the elephant gives us food, you should come here and get this ndiwo vegetable.”

Kalulu the Rabbit replied: “That’s alright King. I understand what you say. But I have never seen ndiwo of this kind before!”

After walking for a distance, Kalulu the Rabbit stopped and said:

“I am sorry chief. I think you should be the one in front to lead the way. I forgot my knife where we stopped a while back.”

Quickly, Kalulu ran back and collected the vegetable and put it in his pocket.

When they arrived at the Elephant’s house, they were warmly received. The Elephant cooked food and served it to his two guests. The Lion sent Kalulu the Rabbit to go and fetch the ndiwo vegetable from the bush.

Kalulu took out the green vegetables and said:

“Here King! I got the ndiwo already so that there would be no delays when we eat food.”

In this way the Lion’s trick failed this time because Kalulu the Rabbit also ate the food and was satisfied.

When it was dark in the evening, the Elephant showed the Lion and Kalulu a place where they could sleep. The Lion got a nice mat where he could sleep. But Kalulu only slept on hard tree fibers. At dawn, Kalulu began to sing a song.

“Those who sleep on hard tree fibers are tough; yea! yea!

Those who sleep on a nice mat become tired; yea! yea!”

When he heard Kalulu’s song, the Lion woke up and said:

“What are you singing about Kalulu? Would you stop it because I am trying to sleep!”

But Kalulu the Rabbit said:

“Forgive me King, my grandfather taught me this song. He said if you are on a journey and you want to sleep comfortably, you should sleep on tree fibers.”

In this way the Lion was attracted to Kalulu’s idea. and said:

“Please Kalulu let me try to lay down on the tree fibers.”

The Lion fell asleep very deeply. Kalulu the Rabbit woke up and used the tree fiber to tie up the lion. After tying up the Lion in this way, Kalulu got some fire and set the fibers alight. When the Lion felt the heat and the pain from the fire, he tried to free himself but could not.

The Lion began to shout: “Oh! My! Oh! My! I am dying. Kalulu please untie me!”

But Kalulu the Rabbit ran away out of sight as fast as he could.

About the Author

Mwizenge S. Tembo obtained his B.A in Sociology and Psychology at University of Zambia in 1976, M.A , Ph. D. at Michigan State University in Sociology in 1987. He was a Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Institute of African Studies of the University of Zambia from 1977 to 1990. During this period he conducted extensive research and field work in rural Zambia particularly in the Eastern and Southern Provinces of the country. He is currently Professor of Sociology at Bridgewater College in Virginia. This material was gathered during a research field trips (1980 and 1985) sponsored by the Institute for African Studies and in August 1993 partially sponsored by a grant from the Bridgewater College Flory Development Fund and supported by the Institute of African Studies of the University of Zambia to whom he is very grateful. Thanks to all respondents in the villages and the Lundazi District Governor’s office.

References

Books

Mwizenge S. Tembo, Legends of Africa, New York: Michael Friedman Publishing Group, Inc., 1996

Mwizenge S. Tembo, Afrikaanse Mythen en Lengenden, (Translated into Afrikaans, the language of about two million white Dutch descendants in South Africa), New York: Michael Friedman Publishing Group, Inc., 1996

Articles

J. Brewer, Kalulu ndi Nyama Zinzace, (Kalulu and His Brother Animals), Longmans, Green and Company, London, 1946. Translated from Nyanja Zambian language into English by Mwizenge S. Tembo, March 1986. (translated version unpublished.)

Tembo, Mwizenge., What Good is Etiquette?: Understanding the Norms of Good Behavior in Zambia, The World & I, November 2002.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. Coming from the Earth: Foodways of the Tumbuka of Eastern Zambia, The World & I, May 1997.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. When Daybreak Comes: Folktales from the Tumbuka of Eastern Zambia, The World & I, March 1997.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. The Cunning Prey: Animal Tales from the Tumbuka of the Eastern Zambia, The World & I, January, 1997.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. Dimbas and Dambos: Village Gardens of Eastern Zambia, The World and I, June 1994.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. Delicious Insects: Seasonal Delicacies in the Diet of Rural Zambians, The World & I, October 1993.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. Tasty Mice: The Significance of Mice in the Diet of Zambia’s Tumbuka People, The World & I, November 1992.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. Where Chickens Sleep in Trees: The Importance of Chickens in Rural Zambia, The World & I, September 1991.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. An Assessment of Appropriate Technology Needs of Gwazapasi and Mkanile Villages of the Lundazi District of Rural Zambia, Eastern Africa Journal of Rural Development, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1981.

Tembo, Mwizenge S., Mwila, Chungu., and Hayward, Peter., An Assessment of Technological Needs in Three Rural Districts of Zambia, Human Aspects of Technology in Zambia, Preliminary Report, Institute for African Studies, University of Zambia, No. 1, February 1982.

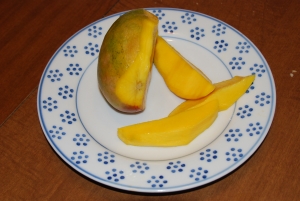

When this author lived in the villages of rural Zambia in Lundazi in the 1950s with his grandparents, he remembers eating and enjoying Mangoes virtually every day during the Mango season. Grandparents and mothers used to prohibit us children from eating Mangoes in the late afternoon, because then we would not be able to eat dinner or supper of the Nshima staple meal. Mangoes are such a filling fruit. At the end of the growing season in early March, my grandparents and virtually all household still had maize and peanuts stored from the previous season still available which they called chomba or old harvest food from the previous season which was usually April of the previous year.

When this author lived in the villages of rural Zambia in Lundazi in the 1950s with his grandparents, he remembers eating and enjoying Mangoes virtually every day during the Mango season. Grandparents and mothers used to prohibit us children from eating Mangoes in the late afternoon, because then we would not be able to eat dinner or supper of the Nshima staple meal. Mangoes are such a filling fruit. At the end of the growing season in early March, my grandparents and virtually all household still had maize and peanuts stored from the previous season still available which they called chomba or old harvest food from the previous season which was usually April of the previous year.