Conceptualization of Technology Among Men and Women in Rural Zambia

[This study investigated the conceptualization of Appropriate Technology for Food Processing Among Men and Women in Rural Zambia. The study was sponsored by the Institute for African Studies of the University of Zambia as requirement for the author’s Ph. D. dissertation in 1985. During the field work in Zambia, many individuals offered their assistance and cooperation that made the study possible. Dr. Stephen Moyo, then Director of the Institute, Mr. Chiyanika of the Staff Development Office, and the Lundazi District Governor and all the employees. Mr. Dominique Muchimba, Mr. Nkhata, and Ms. Christine Phiri were Research Assistants. This paper was first written on June 22nd, 1990]

Introduction

During the past two decades, two crucial themes have been focused on simultaneously in Third World development. First, appropriate technology (AT) dominated debates on development strategies during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Schumacher, Jequier, and Dickson¹ were some of the prominent advocates.

Second, the campaign for sexual equality and women’s liberation in Africa and emphasis on empowering women in Third World development is represented in some of the early primary literature by Boserup, and later Rogers and Reiter². Huston³ outlined the World Plan of Action for 1975-1985 Decade for Women formulated by the International Women’s Year conference held in Mexico City in 1975. The plan recognized the types of burdens third World women carry and suggested possible solutions. The UN declaration of International Decade for Women accelerated the process. By the mid 1980s both gender articulation and appropriate technology had been the focus in development programs in many Third World countries.

One of the fundamental questions which was never addressed in studies in African development is how do participants in development, men and women themselves, conceptualize appropriate technology.

Aims and Objectives:

Men and women in rural Zambia conceptualize appropriate technology depending on the opportunities they have to be exposed to technology. These opportunities are not the same for men and women for three basic reasons. First, in the rural community’s social structure, men and women have different amounts of power. This power accounts for differences in access and exposure to agricultural technology. Second, differential access and exposure to agricultural technology by men and women is due to inequality in the gender division of labor in the production process. Third, the unequal power and gender division of labor is responsible for men and women’s differential participation in modern institutions and potential exposure to new ideas about agricultural technology.

Differences in power between the genders in the rural community may lead men and women to view appropriate technology differently. Gender inequality in division of labor may in turn lead to differential access and exposure to technology. This may contribute to how men and women view appropriate technology.

Like any developing country, people in rural Zambia in Southern Africa have been exposed to various influences. The social structure, sexual division of labor, implements and methods in food processing and preservation have undergone tremendous changes. The traditional and modern have been intertwined. Have these changes impacted rural women in Zambia differently from men? The aim of this study is to investigate how a sample of men and women in rural Zambia conceptualize appropriate technology for food processing and preservation.

Hypotheses:

According to the literature, appropriate technology for rural people is defined as technology which meets criteria such as convenience, low cost, output, time saving factors, affordability, and local availability of resources for use in the technology.4 But in this researcher’s view, knowledge, awareness and use of these criteria by rural people in defining what is appropriate technology is not transmitted through a vacuum. Instead, knowledge about technology is conveyed through the social structure and social organization of the day-to-day existence of people in the rural community. The social structure often has social and cultural constraints and processes.

Three aspects of the rural social structure are thought to influence men’s and women’s views of appropriate technology. The distribution of power, gender inequality in the division of labor, and participation in modern institutions. This is consistent with studies conducted in rural Africa by Boserup, Muntemba, Tinker and Bramsen, and Skjonsberg.5 Gender inequality in the division of labor is such that women in the Lundazi District experience most of the burden involved in food processing, preservation, and storage. This view is consistent with studies by Staudt, Tinker and Bramsen, and Spencer.6 Women perform these tasks and household chores often using poor, less productive technology. Because women carry out more food processing and preservation tasks than men, they have greater awareness of and exposure to the burdens and limitations of these aspects of gender division of labor of rural subsistence life. Therefore, women can be expected to conceptualize appropriate technology for food processing, preservation, and storage better than men.

From the preceding discussion the hypothesis to be tested in the study is:

- The sample of women respondents will score higher on the appropriate technology questionnaire on items regarding food processing, preservation, and storage than the sample of men respondents.

Methodology and Sampling:

The two principle research methods employed yielded both qualitative and quantitative data. These were survey and field methods.

The survey was conducted in the western half of the district including part of the southern area(see map). The area had an estimated total population of 44,631 with a total list of 435 villages and an average of 102 people per village.7 A total of twenty-four villages were randomly drawn from the list of villages. From each of the villages, a total of six adult respondents were randomly selected; three men and three women. A total of 144 respondents were interviewed.

The structured questionnaire consisted of twenty-two items on appropriate technology in the area of food production, food processing, preservation and storage. The questionnaire was divided into three parts: food production; food processing, preservation and storage; and Contact with Significant Social Change Institutions. (COSISOCHINS) The objective of the questions was to find out how the respondents conceptualized appropriate technology.8

Questionnaire items on food processing, preservation, and storage focused on several common traditional and modern methods of processing food. For example, respondents were asked to compare solar drying and canning as methods of processing and storing food. Did they think one was better than the other? In the respondent’s opinion, what was the most appropriate method of processing, preserving, and storing food for themselves in the village. Responses to these questions were expected to reflect how men and women conceptualize appropriate technology for food processing.

Data Analysis and Discussion:

The assumptions about gender differences in processing technology were based on the sexual inequality in the division of labor in the social organization of the production process. Women in the rural community are primarily responsible for food processing. They bear the burdens of food processing and often use poor traditional technology to perform these tasks. It was assumed that since women are the ones with greater exposure to and performance of these tasks, they conceptualize and evaluate appropriate technology for food processing, preservation, and storage better than men. The findings of the study did not confirm the hypothesis.

Tables One and Two show that there were insignificant differences in how men and women viewed appropriate technology for food processing.

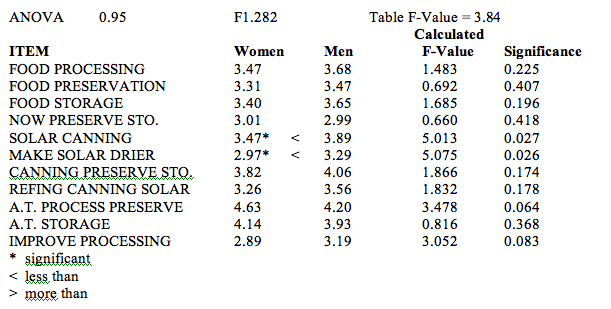

ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE (ANOVA) OF APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY FOR FOOD PROCESSING, PRESERVATION AND STORAGE BY GENDER

Out of the eleven items on food processing, preservation and storage, there were significant sexual differences in only two items at P < 0.05. Even in the two items, women scored significantly lower than men.

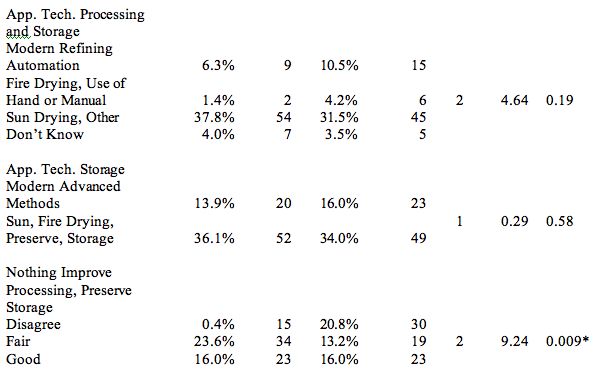

APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY FOR FOOD PROCESSING, PRESERVATION AND STORAGE BY GENDER

______________________________________________________________________________

*Significant Differences at P < 0.05

N = 144

Women = 72

Men = 72

Table Two shows that only one item of eleven, or only nine percent, showed significant gender differences. In the item “there is nothing we can do to improve food processing, preservation, and storage” the findings in the table show that men disagreed with the statement more than women.

The sex role task overlap explanation applies to the lack of significant differences in how men and women view appropriate technology for food processing, preservation and storage. Although women are involved in most food processing and preservation,9 often tiring and back breaking processes,10 men also acquire somewhat similar knowledge and familiarity with the same tasks. Men see or observe women process and preserve the food in daily life. Sometimes, men participate in food processing by shelling maize and groundnuts before either is pounded into flour or sold on the commercial market. Therefore the men probably share conceptions and evaluations which are somewhat similar to that of women.

Insignificant sexual differences in the conceptualization of appropriate technology for food processing persist when age, education, income and marital status were held constant.11 Overall, eighty-two of a total of eighty-eight items or ninety-four percent of the items yielded insignificant gender differences in the conceptualization of appropriate technology for food

processing, preservation, and storage. The persistent pattern of even more insignificant gender differences in the evaluation of appropriate technology for food processing when age, education, income and marital status are held constant suggests the sex role task overlap is even more evident in this area of the Lundazi District sexual division of labor and social organization of the production process. Men and women perhaps share more of these tasks in their day to day village existence in spite of differences in age, formal education, income level, and marital status.

For illustrative purposes, in the items “Solar drying is better than canning,” “what is the appropriate technology for food storage,” “canning is best,” and “how are your current methods of food preservation,” there were no differences in how men and women responded. Men and women agreed with the statement that solar drying was better than canning; responded that sun drying and traditional storage methods were the appropriate technology for food storage; disagreed that canning food was best for them as a method of storing food; and responded that the current methods of preserving food were good. These identical responses on virtually all other items were consistently given by both men and women whether they were young or old had low or high formal education, had low or high income, had monogamous or polygamous marital statuses.

Food Processing, Preservation, and Storage:

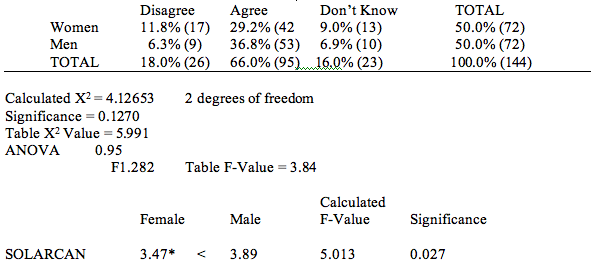

The few items showing significant differences suggest these areas of food processing are sex exclusive. The item “Solar drying food is better than canning” is an illustration. In Table Three the Analysis of Variance shows the differences between men and women to be significant at P < 0.05 while the Chi-Squared Test did not yield any significant differences at P > 0.05. The differences are assumed to be significant any way since ANOVA is stronger than the Chi-Squared Test.

ITEM 5. SOLAR DRYING FOOD IS BETTER THAN CANNING BY GENDER

Women do so much sun drying of food, and it is so strenuous and tedious a task that the women are more likely to disagree with the statement that it is better than canning. In other words, the women are willing to try anything new that would allow them freedom from using sun drying to preserve their food. Since men do not take part in such tasks, they are likely to assume solar drying is better than canning. Several studies confirm food processing in general is not only tedious and physically demanding on rural women in Africa, but constitutes a significant addition to an already heavy load for women.

Bryson discusses food crop production and sexual division of labor in sub-Saharan Africa, using data from the Ethnographic Atlas.12 She concludes that women overall account for fifty-two percent of the labor as opposed to men who account for only nineteen percent. Bryson says: “processing is also in the women’s sphere of responsibility…the benefits to be derived from

improved food processing and storage should not be overlooked, as this would have the same effect as increased production of the basic product.”13

Studies conducted in rural Kenya, Zaire, Zambia and Gambia found that women worked six to ten hours daily in the fields. “The women’s work load during off-peak seasons is only slightly less demanding. Estimates show that when the number of hours spent in the fields is lower, the number of hours spent on other activities such as collecting water and firewood, processing and preparing food and caring for children increases.”14

Rural women, including those in this sample from the Lundazi district, spend a great deal of time in processing like thrashing, shelling, and hand pounding of cereals, collecting firewood, and fetching water. As an appropriate technology explored in food processing in this study, solar drying was probably perceived to be as tedious as the traditional sun drying as a means of preserving food for the women. Therefore, this is probably why the women disagreed with the statement that solar drying was any better than canning as a method of processing, preserving, and storing food. Similar explanations can be used for the few items that yielded significant differences.15

Conclusion

The notion of sex role task overlap explains the lack of significant gender differences in the conceptualization of appropriate technology of food processing and preservation in rural Zambia. The few items that yielded significant gender differences might reflect more fundamental underlying social conditions.

First, exclusiveness in the sexual division of labor of a particular activity might account for the differences. For example, women often exclusively bear the physical burden and experience of carrying heavy loads of unprocessed food, the actual processing, and preservation. This is perhaps why a few specific items like “canning food”, men and women showed significant differences.

Second, the subordinate and inferior social status of the women perhaps undermines their confidence and outlook. This is perhaps why on a few specific items women seemed to be less confident and more pessimistic than men.

Much as sex task role overlap in the conceptualization of appropriate technology for food processing resulted in insignificant differences, the inferior status of women in rural Zambia still has insidious effect on women’s self confidence about changing and improving their circumstances.

1E. F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: Economics as If people Mattered. (New York: Harper and Row, 1973). Nicholas Jequier, (ed.). Appropriate Technology: Problems and Promises. (Paris: Development Center for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (O.E.C.D) 1976). David Dickson, Alternative Technology and the Politics of Technological Change. (London, Fontana: Collins, 1974). Chapter 1.

2Ester Boserup, Woman’s Role in Economic Development. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1970). Barbara Rogers, The Domestication of Women: Discrimination in Developing Societies. (London: Kogan page Limited, 1980). Rayna R. Reiter, Toward and Anthropology of Women, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1975).

3Peridta Huston, Third World Women Speak Out: Interviews in Six Developing Countries on Change, Development and Basic Needs. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1979). p. xv.

4E. F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: Economics as If people Mattered. (New York: Harper and Row, 1973). Nicholas Jequier. (ed.). Appropriate Technology: Problems and Promises. (Paris: Development Center for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (O.E.C.D.) 1976). David Dickson, Alternative Technology and the Politics of Technological Change. (London, Fontana: Collins, 1974). Chapter 1.

5Ester Boserup, Woman’s Role in Economic Development. (New York: St. Martins. Press, 1970). Shimwaayi Muntemba, “Women as Food Producers and Suppliers in the Twentieth Century: The Case of Zambia, “Development Dialogue. 1-2, 1982. Irene Tinker, and Michele Bo Bramsen, (eds.). Women and World Development. (Washington D.C.: Overseas Development Council, April 1976). Else Skjonsberg, The Kefa Records: Everyday Life Among Women and Men in a Zambian Village. (Oslo: U-Landsseminaret, No. 21, 1981).

6Kathleen A. Staudt, “Women Farmers and Inequalities in Agricultural Services.” Women and Work in Africa. Edited by Edna G. Bay, Boulder, (Colorado: Westview press, 1982) pp. 207-224. Tinker, Irene and Bo Bramsen, Michele. (eds.). Women and World Development. (Washington D. C. : Overseas Development Council, April 1976). Spencer, Dunstan S.C.

“African Women in Agricultural Development: A Case Study in Sierra Leone.” (East Lansing, African Economy Program: Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural Economics, Working Paper No. 11, April, 1976).

7sup>This data was collected from the Lundazi District governor’s Office. The Lundazi District, particularly the plateau, was a good site because social and economic conditions in the district presented an excellent opportunity for the survey research design. The plateau supports better cultivation, has better communication and transportation patterns throughout the year, and a larger population concentration than the valley. The area villages are generally accessible even during the rainy season. When the limited resources of the dissertation were assessed, it was found more economical and suitable to limit the research site and survey to the plateau area of the Lundazi District. Moreover, the researcher was familiar with the area, having previously conducted research there.

The researcher recorded in writing and on tape all significant social events influencing respondents” daily lives but were not covered in the formal survey. The events were particularly those pertaining to food production, processing, preservation and storage. Random sampling was used in the survey and covered approximately half of the Lundazi District. Because the basic social structure of the villages in the district was the same, drawing the sample from only half of the district did not necessarily increase chances of a biased sample.

The sampling was performed using the latest records and population estimates from the office of the District Governor of the Lundazi district. The office of the District Governor is a Zambian government administrative body which executes and supervises the political, economic and social activities, projects, services of the Lundazi district in close liaison with other non-government institutions.

The District Social Secretary provided the population estimates for the research area. The population estimates were based on polling stations statistics of the number of adults registered to vote. The actual number was then multiplied by three. The multiplication by three of the total number of registered voters proved to be a reliable estimate because it was consistent with a more accurate random head count of a sample of villages. The estimate included people under sixteen years of age, aliens and those who did not bother to register for voting since voting was not compulsory.

8Full details of findings regarding COSISOCHINS are in the dissertation. Mwizenge S. Tembo, Conceptualization of Appropriate Technology in Lundazi District of Rural Zambia. (East Lansing: Michigan State University, 1987). Dissertation. Chapter 6.

9Irene Tinker, and Michele Bo Bramsen, (eds.). Women and World Development. (Washington D. C.: Overseas Development Council, April 1976).

10Mwizenge S. Tembo, “An Assessment of Appropriate Technology Needs of Gwazapasi and Mkanile Villages of Lundazi District of Rural Zambia.” Eastern Africa Journal of Rural Development. (Vol. 14, No 1 and 2, 1981).

11See Appendix for Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7.

12Judy C. Bryson, “Women and Agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for Development (An Exploratory Study),” in African Women in the Development Process. Edited by Nici Nelson. (Totowa, N.J.: Frank Cass and Co., 1981). p. 114. The Ethnographic Atlas was a series of data collected on various cultures in the world. Researchers drew on the data to study particular societies, following strict statistical procedure. Bryson based her analysis on Murdock’s work (1967: 114).

13Ibid, p. 114.

14Marilyn Carr, “Technologies for Rural Women: Impact and Dissemination” in Technology and Rural Women: Conceptual and Empirical Issues. Edited by Iftikhar Ahmed, (Boston: George Allen and Unwin, 1985). p. 117. Economically Appropriate Technologies for Developing Countries: An Annotated Bibliography. (London: Intermediate Technology Publications, Ltd., 1976).

15The possible detailed explanations can be found in the dissertation. Generally, the findings on these items suggest that the dominant social status of men enables them to express greater optimism. Women’s subordinate status perhaps accounts for their pessimism about whether they

can do anything to change or improve their current condition. Mwizenge S. Tembo, Conceptualization of Appropriate Technology in Lundazi District of Rural Zambia. (East Lansing, Michigan State University, 1987). Dissertation.

REFERENCES

Anastasi, Anne. Differential Psychology: Individual and Group Differences in Behavior.

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1958.

Andree, Carolyn. Appropriate Technology: A Selected Annotated Bibliography. East Lansing:

Non-Formal Education Information Center, Michigan State University, 1982.

Araji, Sharon K. and Al-Jabouri, Omaima. “Factors and Policies Associated with Rural

Women’s participation in Iraqi Extension Centers.” Michigan State University, Women in International Development, Working paper No. 115, May 1986.

Bangura, Sorie J.B. “Appropriate Technology in Rural Development.” In Fundamental Aspects of Appropriate Technology. J. de Schutter and G. Bemer (eds.) Delft, Netherlands: Delft University Press, 1980.

Bay, Edna G. (ed.). Women and Work in Africa. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1982.

Bert, Robert J., and Whitaker, Jennifer Seymour, (eds.). Strategies for African Development.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Bernard, Jessie, (eds.). “Research on Sex Differences: An Overview of the State of the Art,” in

Women, Wives, Mothers. New York: DeGruyter Aldine Publishers, 1975.

Blalock, Hubert M. An Introduction to Social Research. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey:

Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1970.

Boserup, Ester. Woman’s Role in Economic Development. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1970

Bryson, Judy C., “Women and Agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for Development

(An Exploratory Study),” in African Women in the Development Process. Edited by Nici Nelson. Totowa, N.J.: Frank Cass and Co., 1981.

Buvinic, Mayra, Lycette, Margaret A. and McGreeny, William Paul (eds.). Women and Poverty

in the Third World. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University, 1983.

Cain, Melinda L. “Overview: Women and Technology – Resources for Our Future,” in Women and Technological Change in Developing Countries. Edited by Roslyn Dauber and Melinda L. Cain. Boulder, Colorado: Westview press, Inc., 1981.

Canadian Hunger Foundation and Brace Institute. A Handbook on Appropriate Technology. Ottawa: the Foundation and Institute, 2nd ed., April 1973.

Carr, M. Economically Appropriate Technologies for Developing Countries: An Annotated

Bibliography. London: Intermediate Technology Publications, Ltd., 1976.

Carr, Marilyn. “Technologies for Rural Women: Impact and Dissemination,” in Technology

and Rural Women: Conceptual and Empirical Issues. Edited by Iftikhar Ahmed, Boston: George Allen and Unwin, 1985.

Cernea, Michael. “Sociological Dimensions of Extension Organization: The Introduction of the

T & V System in India,” in Extension Education and Rural Development. Edited by Bruce R. Crouch and Shankariah Chamala, Vol. 2, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1981.

Chaney, Elsa. Simmons, Emmy and Staudt, Kathleen. Women in Development: Background

Papers for the United States Delegation World Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development FAO Rome 1979. Washington, D. C.: Agency for International Development, July 1979.

Charlton, Sue Ellen M. Women in Third world Development. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1984

Collier, Jane Fishburne. “Women in Politics,” in Woman, Culture, and Society. Edited by

Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo and Louise Lamphere. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1974.

Coombs, Philip H. “What Will It Take To Help The Rural Poor?” in Meeting the Basic Needs of

the Rural Poor. Edited by Philip H. Coombs. New York: Pergamon Press, 1980.

Congdon, R. J. (Ed.). Introduction to Appropriate Technology: Toward a Simpler Life Style.

Emmons, P. A.: Rodale Press, 1977.

D’Andrabe, Roy G. “Sex Differences and Cultural Institutions.” in The Development of Sex

Differences. Edited by Eleanor MacCoby. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1966.

Dauber, Rosly, and Cain, Melinda L. (Eds.). Women and Technological Change in Developing

Countries. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, Inc., 1981.

Dickson, D. Alternative Technology and the Politics of Technological Change. London,

Fontana: Collins, 1974.

Dobriner, William M. Social Structures and Systems: A Sociological Overview. Pacific

Palisades: California, Inc., 1969.

Due, Jean M. and White, Marcia. “Female-Headed Farm Households in Zambia: Further

Evidence of Poverty.” East Lansing, Women in International Development: Michigan State University, June 1986.

Due, Jean M.; Mudenda, Timothy; and Miller, Patricia. “How do Rural Women Perceive

Development? A Case Study in Zambia,” East Lansing, Women in International Development: Michigan State University Working Paper No. 63, August 1984.

Due, Jean M. and Mudenda, Timothy. “Women’s Contributions to Farming Systems and

Household Income In Zambia,” East Lansing, Women in International Development: Michigan State University, Working Paper No. 85, May 1985.

Dumont, Rene’ and Mottin, Marie-France. Stranglehold on Africa. Translated from French by

Vivienne Menkes. London: Andre’ Deutsch Limited, 1983.

Edwards, Alfred L.; Oyeka, Ikewelugo C. A.; and Wagner, Thomas W. (eds.). New Dimensions

of Appropriate Technology: Selected Proceedings of the 1979 Symposium. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1980.

Etzioni, Amitai. An Immodest Agenda: Rebuilding America Before the 21st Century. New

York: McGraw0Hill Book Company, 1984.

Eicher, Carl K. “International Technology Transfer and the African Farmer: Theory and

Practice.” East Lansing, Agricultural Economics: Michigan State University, Working Paper 3/84, May 1984.

Evans, David H., Planning and Implementing Integrated Rural Development: A Review of the

Integrated Rural Development Project in the North-Western Province of Zambia. Kabompo (Zambia): Integrated Rural Development Project, May 1981.

Frey, Frederick W. “Cross-Cultural Survey Research in Political Science.” The Methodology of

Comparative Research. Edited by Robert T. Holt and John E. Turner. New York: The Free Press, 1970.

Garg, M. K. Some Developments of Appropriate Technology for Improving Physical Amenities

in Rural Homes. Case Study Series No. 2, Lucknow, India: Appropriate Technology Development Association, February 1978.

Glass, G. V. and Stanley, J. C. Statistical Methods in Education and Psychology. Englewood

Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1970.

Greenwood, Davydd J. “Community-Level Research, Local-Regional-Governmental

Interactions, and Development Planning: A strategy for Baseline Studies.” Rural Development Occasional Paper No. 9, Cornell University: Rural Development Committee, 1980.

Hays, William. Statistics for Psychologists. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1963.

Heath, Dwight B. “Sexual Division of Labor and Cross-Cultural Research.” Social Forces. Vol.

37, No. 1, October 1958.

Hirschmann, David. “Bureaucracy and Rural Women: Illustrations from Malawi.” East

Lansing, Women in International Development, Michigan State University: Working Paper No. 71. November, 1984.

Hoppers, W.; Banda, C.; Kamya, A.; Schultz, M. and Tembo, M.S. Youth Training and

Employment in Three Zambian Districts. Lusaka: University of Zambia, Manpower Research Report, No. 5, 1980.

Huston, Perdita. Third World Women Speak Out: Interviews in Six Developing Countries on

Change, Development and Basic Needs. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1979.

Hyden, Goran. “African Social Structure and Economic Development,” in Strategies for African

Development. Edited by Robert J. Berg and Jennifer Seymour Whitaker. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Irwin, M.; Klein, R.; Engle, P.; Yarbrough, C. and Nerlove, S. “The Problems of Establishing Validity in Cross-Cultural Measurements.” Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 285, 1977.

Jaquette, Jane S. and Staudt, Kathleen A. (eds.) Women and Developing Countries: A Policy Focus. New York: Haworth Press, 1983.

Jedlicka, Allen D. Organization for Rural Development: Risk Taking and Appropriate Technology. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1977.

Jequier, N. (ed.). Appropriate Technology: Problems and Promises. Paris: Development Center for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (O.E.C.D.) 1976.

Jiggins, J. “Female-headed Households: Mpika Sample, Northern Province.” Lusaka: University of Zambia, Rural Development Studies Bureau, Occasional Paper No. 5, 1980.

Kessler, Suzanne and McKenna, Wendy. Gender: An Enthnomethodological Approach. New York: John Wiley, 1978.

Kingsley, Phillip. “Technological Development: Issues, Roles and Orientation for Social Psychology.” Lusaka: University of Zambia, Department of Psychology, September 1980 (unpublished).

Koloko, Edwin M. “Intermediate Technology for Economic Development: Problems of Implementation,” in Development in Zambia. Edited by Ben Turok. London: Zed Press, 1979.

Labovitz, Sanford and Hagedorn, Robert. Introduction to Social Research. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1971.

Lenski, Gerhard and Lenski, Jean. Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1982.

Lindblad, C. and Druben, L. Small Farm Grain and Storage. Vols. 1-3. Peace Corps Program Lips, Hilary M. and Colwill, Nina Lee. The Psychology of Sex Differences. Englewood Cliffs,

New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1978.

Long, Norman. Introduction to the Sociology of Rural Development. London: Tavistock Publications, 1982.

Loufti, Martha Fetherolf. Rural Women: Unequal Partners in Development. Geneva: nternational Labor Office, 1980.

Maccoby, Eleanor and Jacklin, Carol N. The Psychology of Sex Differences. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1974.

McCalman, Kate. “We Carry a Heavy Load: Rural Women in Zimbabwe Speak Out.” Reportof a Survey Carried Out by the Zimbabwean Women’s Bureau. Salisbury: Zimbabwe “Women’s Bureau, December 1981.

Muntemba, Shimwaayi. “Women as Food Producers and Suppliers in the Twentieth Century: The Case of Zambia,” Development Dialogue. 1-2, 1982.

Mwila, S. C. “Basic Needs: Availability and Distribution of Soap in Zambia.” Discussion Paper, Lusaka: R.D.S.B., for ILO/JASPA, September, 1980.

Parlee, Mary Brown. “Review Essay: Psychology.” Signs. 1 (1) 119-138.

Przeworski, A. and Teune, H. “Part Two: Measurement.” The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1970.

Republic of Zambia. Country Profile: Zambia 1984. Lusaka: Central Statistical Office, 1984.

Republic of Zambia. Census of Population and Housing, 1969 Final Report. Vol. IIc: Eastern Province. Lusaka: Central Statistical Office, 1974.

Republic of Zambia, Ministry of Health. Reports for Years 1973-1977. Lusaka: Government Printer, 1980.

Republic of Zambia. Third National Development Plan 1979-83. Lusaka: Office of the President, National Commission for Development Planning, October 1979.

Robinson, Austin. Appropriate Technologies for Third World Development. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979.

Rogers, Barbara. The Domestication of Women: Discrimination in Developing Societies. London: Kogan page Limited, 1980.

Rogers, Everett M. Communication of Innovations: A Cross-Cultural Approach. Second Edition, New York: The Free Press, 1971.

Sachs, Reinhold G. “Functions and Training of Agricultural Extension Officers: With Special Regard to the Zambian Case,” in Extension Education and Rural Development. Edited by Bruce R. Crouch and Shankariah Chamala. Vol. 2, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1981.

Sanday, Peggy R. “Female Status in the Public Domain,” in Woman, Culture, and Society. Edited by Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo and Louise Lamphere. Stanford: California, Stanford University Press, 1974.

Schlie, Theodore W. “Appropriate Technology: Some Concepts, Some Ideas, and Some Recent

Experiences in Africa.” Eastern African Journal of Rural Development. Vol. 7, No. 1 and 2, 1974.

Sherman, Julia A. Sex-Related Cognitive Differences: An Essay on Theory and Evidence. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, 1978.

Schumacher, E. F. Small is Beautiful: Economics as If people Mattered. New York: Harper and Row, 1973.

Schuman, Howard. “The Random Probe: A Technique for Evaluating the Validity of Closed Questions,” in Comparative Research Methods. Edited by Donald P. Warwick and Samuel Osherson. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1973.

Skjonsberg, Else. The Kefa Records: Everyday Life Among Women and Men in a Zambian

Village. Oslo: U-Landsseminaret, No. 21, 1981.

Spencer, Dunstan S. C. “African Women in Agricultural Development: A Case Study in Sierra

Leone.” East Lansing, African Economy Program: Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural Economics, Working paper No. 11, April, 1976.

Staudt, Kathleen. Agricultural Policy Implementation: A Case Study from Western Kenya.

West Hartford, Connecticut: Kumarian Press, 1985.

Staudt, Kathleen A. “Women Farmers and Inequalities in Agricultural Services.” Women and

Work in Africa. Edited by Edna G. Bay, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1982.

Stoecker, Barbara J.; Montgomery, Evelyn I.; and Gott, S. Edna (eds.). Developing Nations:

Challenges Involving Women. Lubbock, International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land. University: Texas Tech University, 1982.

Tembo, Mwizenge S. Conceptualization of Appropriate Technology in Lundazi District of Rural

Zambia. East Lansing: Michigan State University, 1987. Dissertation.

Tembo, M. S.; Mwila, S. C.; and Hayward, P. B. An Assessment of Technological Needs in

Three Rural Districts of Zambia. Lusaka: Institute for African Studies, University of Zambia, February 1982.

Tembo, M. S. “An Assessment of Appropriate Technology Needs of Gwazapasi and Mkanile

Villages of Lundazi District of Rural Zambia.” Eastern Africa Journal of Rural Development. Vol. 14, No. 1 and 2, 1981.

Tinker, Irene. “New Technologies for Food Related Activities: An Equity Strategy,” in Women

and Technological Change in Developing Countries. Edited by Roslyn Dauber and Melinda L. Cain. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, Inc., 1981.

Tinker, Irene and Bo Bramsen, Michele (eds.) Women and World Development. Washington

D. C.: Overseas Development Council, April 1976.

Tresemer, David. “Assumptions Made About Gender Roles,” in Another Voice: Feminist

Perspectives on Social Life and Social Science. Edited by Marcia Millman and Rosabeth Kanter. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1975.

United Nations Development Programme. Rural Women’s Participation in Development:

Action Oriented Assessment of Rural Women’s Participation in Development. Evaluation Study No. 3, New York: United Nations Development Programme, June 1980.

Warwick, Donald P. and Lininger, Charles A. The Sample Survey: Theory and Practice. New

York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1975.

Wellesley Editorial Committee. Women and National Development: The Complexities of

Change. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Whitehead, Ann. “Effects of Technological Change on Rural Women: A Review of Analysis

and Concepts,” in Technology and Rural Women: Conceptual and Empirical Issues.” Edited by Iftikhar Ahmed. Boston: George Allen and Unwin, 1985.

World Bank. Accelerated Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington D. C. : The World

Bank, 1980.

Youssef, Nadia Haggag. Women and Work in Developing Societies. Westport, Connecticut:

Greenwood Press, 1974.

TITLE: Conceptualization of Appropriate Technology for Food Processing Among Men and Women in Rural Zambia.

AUTHOR: Mwizenge S. Tembo, *Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Sociology and Anthropology

Bridgewater College

Bridgewater

VIRGINIA 22812

DATE: 22nd June, 1990

ABOUT AUTHOR*: B. A. University of Zambia, M. A., Ph.D. Michigan State University. Former Research Fellow and Lecturer at the Institute for African Studies of the University of Zambia. Now Interim Assistant Professor in Sociology at Bridgewater College.

This study was sponsored by the Institute for African Studies of the University of Zambia as requirement for the author’s Ph. D. dissertation in 1985. During the field work in Zambia, many individuals offered their assistance and cooperation that made the study possible. Dr. Stephen Moyo, then Director of the Institute, Mr. Chiyanika of the Staff Development Office, and the Lundazi District Governor and all the employees. Mr. Dominique Muchimba, Mr. Nkhata, and Ms. Christine Phiri were Research Assistants.