PROCESS OF TRADITIONAL IRON SMELTING IN EASTERN ZAMBIA AND ITS POSSIBLE IMPAC ON APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY

INTRODUCTION

The source, nature, process and spread of traditional iron smelting in East, 1 Central and Southern Africa has been documented.

Fagan 2 asserts that the Zambian Society which is part of Central Africa, lived in a stone age in its historical background in the earliest time. This implies that the inhabitants had neither domestic livestock nor agricultural produce, mining and metal work were unknown. However, by about 2,000 years ago, the inhabitants were hit by major social and economic changes which had spread across Africa. These changes are said to have been introduced from the near East; that is Israel in terms of agricultural techniques, domestic stock and later iron working. Iron tools were first made in the Middle East about 1,500 B. C.

________________________

AUTHOR

B.A. University of Zambia, M.A. Michigan State University. Currently Research Fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Zambia, Lusaka. 1981

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

My regards to the following for their help in this project; UNICEF in collaboration with the Ministry of Youth and Sports of the Republic of Zambia for indirectly sponsoring the study; Professor Serpell, the Director of the Institute of African Studies for his comments and suggestions, Mrs. Mwacalimba for the typing and Dr. Daka of the Chemistry Department of the University of Zambia for his assistance in the interpretation of the chemical analysis of the field samples. My thanks to Jane Myers who is Bowman Hall Secretary at Bridgewater College. She retyped ( in November 2010) the old faded manuscript from 29 years ago in 1981.

“Since the metal gives a much better cutting edge for weapons than copper or bronze, the rulers of the first iron working communities kept their new discovery to themselves, thereby delaying the spread of iron working to other areas of the world. 3

However, despite the human obstacle, the secret was revealed by “roaming professional soldiers. 4 Consequently, the Kings of Egypt were in possession of iron by about 650 B. C.

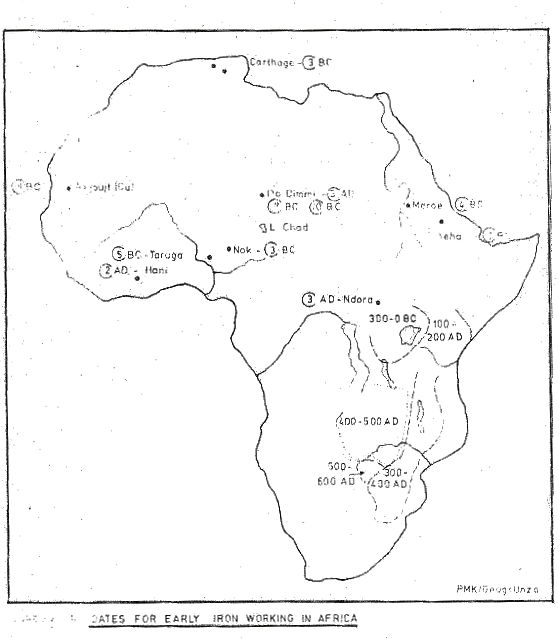

The first significant iron center was at Merve in the Sudan, in Northern Africa. It is believed that the art eventually spread to Southern Sahara, to farmers of Lake Chad, West Africa and further Southwards to the high lands of East Africa. Fagan says that the tools and methods of iron-working had a dramatic effect on the indigenous economy of Africa. “Most scientists agree that the earliest speakers of Bantu languages were responsible for the major spread of ironworking in Sub-Sahara Africa.” 5

Of special interest in this brief history of iron smelting is that the Bantu spread it to Sub-Sahara Africa. The East, Central and Southern Africa were inhabited mostly by Bantu speaking people. This information would suggest that the Bantu spread iron working from East Africa up to the Southern tip of the continent.

This contention is perhaps substantiated by the various pieces of literature which either mention the existence of iron work or describe the process of iron smelting in different regions of Africa. This brief description will particularly cover the areas from the horn of Africa through East and Central up to Southern Africa.

IRON WORK IN THE HORN, EAST, CENTRALAND SOUTHERN AFRICA

Todd 6 also reiterates that the oldest hypothesis suggests that iron working spread from the Nile Valley Southwards to Merve in the Sudan through which it spread to West Africa as well as through East Africa to the South. In her summary of the theories of the African Iron Age, Todd contends that through radio carbon dating methods, iron working had already spread to most parts of Africa by the year 1600. This process took a period of 3,000 years. She also asserts that the literature available indicates that in certain regions of Africa, the iron working might have evolved internally. The most relevant phenomenon however, is the field work she conducted in 1973 among the Dimi people who lived in the northern part of the Omo Valley in South West Ethopia. She states that the manufacture of iron is still an important industry among the Dimi even in contemporary times. She describes the Dimi bloomer process of smelting iron in precise detail including the chemical analysis of Ethopian furnace slags, clay and ores. The significance of the study is not only the tremendous detail regarding the process of iron smelting but the existence of the iron work perse perhaps confirms the hypotheses that iron work originally spread from this part of the African continent to East Central and Southern Africa.

Todd and Charles 7 in their attempt to use iron artifacts to determine the original and migration routes of Iron Age people, suggest that iron metallurgy spread from Meroe to the rest of Africa through two major Southern routes: the region of the White Nile and Ethiopian Highlands.

It is further asserted by the two authors that expansion of the Bantu from Southern Sudan spread iron metallurgy to East, South and Central Africa.

“Ninety percent of people in South Central Africa speak Bantu languages, which are related to the Western Sudanic languages from which they are thought to have differentiated, two to three thousand years ago.” 8

At a later stage, two routes of the spread of iron working are suggested; the Western Stream from Lake Chad. This is substantiated by the prevalence of pottery associated with the early iron age West and South of Lake Victoria. The Eastern stream is associated with Kwale pottery and by C 1600 iron working is found south of the Limpopo in the Southern Africa.

The second aspect of the iron work is the process of iron smelting which was one of the principle objectives of the present author’s field research in Lundazi district of Eastern Zambia. Similar studies with identical objectives have been conducted in Ethiopia by Todd, 9 in Northern Zambia by Quick 10 and in Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) by Cook 11. Some of the findings from these studies will be used as points of contrast in the conclusion of the report.

AIM

The principal aim of the research project was to document the exact procedure which was involved in the process of iron smelting, how the raw material was found, social consequences and organization of iron work, metallurgical constituents of the raw material and slag and finally to speculate about the possible connection of the indigenous knowledge about iron smelting and the theoretical notions pertaining to and significance of appropriate technology in Zambia.

METHOD SAMPLE AND AREA OF STUDY

The major tool of the study was a semi-structural questionnaire which consisted of 10 questions. 12 The responses to the questions were recorded on a tape recorder as the responses to follow up questions were long, winding and intricate in certain respects. Pictures of some of the now dilapidated iron Kilns were taken, samples of slag and raw materials were collected for laboratory analysis as well as the physical dimensions of the old Kilns.

The original tentative sample size was 20 men and 20 women born between 1890 and 1935 (45 – 90 years old). As anticipated, the people who met the age criteria and at the same time knew something about iron smelting were so few that within a course of two weeks of searching in a radius of about 50 kilometers around Lundazi, only three men could be interviewed. These were all over sixty years old. There was one man found in each of the three chiefs’ areas; Chief Magodi, Phikamalaza and Kapichila.

The three respondents were interviewed for an average of two hours each which was a total of six hours of interviews.

- Josias Hara, 66 years, Manyara Village, Chief Magodi.

- Japhet Nkata, 79 years old, Engangeni Village, Chief Phikamalaza.

- Andreya Mwandila, 66 years old, Kapichila Village, Chief Kapichila.

The questions concerning the process of iron smelting itself were open to spontaneity. This left the researcher to formulate follow up questions freely to clarify certain aspects of iron smelting which the respondent at that moment was expressing in a vague fashion.

RESULTS

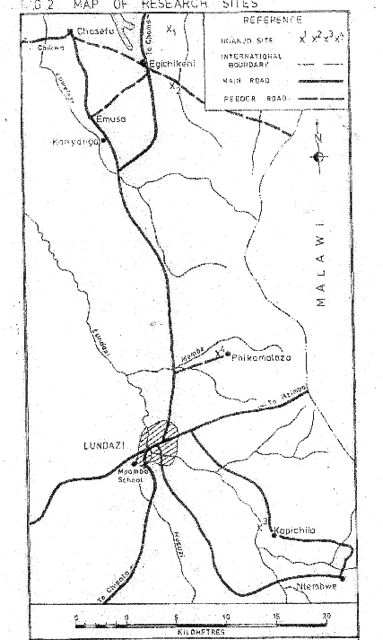

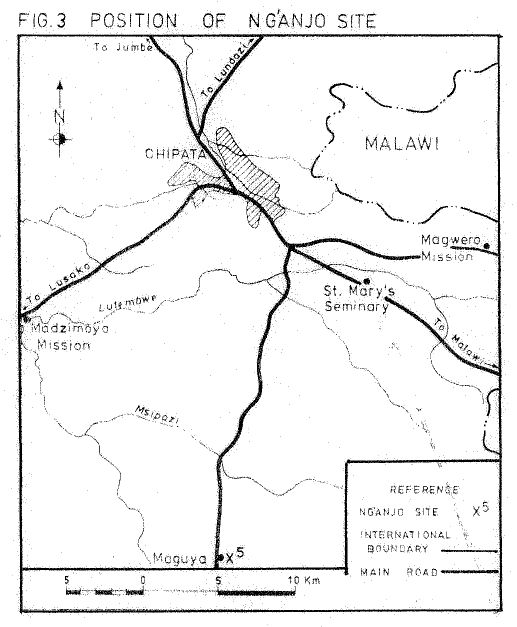

A total of five iron smelting sites were visited of which four were within 50 Km radius of Lundazi Boma as shown on the map in fig. 2. The 5th Kiln was however, located 25 km South-East of Chipata along Chadiza road. (see fig. 3).

The only sites about which measurements were taken were those which were reasonably still intact. Only three out of five met this criteria. The other two sites usually had scattered slag and after very hard searching the site of what used to be ng’anjo was identified.

1ST IRON SMELTING SITE (REFER TO FIG.2)

This was the first of the sites visited. The site was ½ km from Dambo.* the two dilapidated ng’anjo were located at the bottom of an ant-hill. What was visible was two round structures side by side. (see picture 5).

SLAG AND ORE ANALYSIS FINDINGS THROUGH ATOMIC ABSORPTION METHOD

Sample From Site 2: Manyara Village

| Sample Used Minerals And Their Amounts In The Samples | |||||||

| I Fe203 | Cu | Co | Pb | Zn | Ni | Mn | |

| SLAG | 59.09%

(5.909×105) |

0.003%

(30.0) |

0.003%

(30.0) |

0.002%

(20.0) |

0.004%

(40.0) |

0.002%

(20.0) |

0.140%

(1400.0) |

| ORE | 30.08%

(3.008X105) |

0.007%

(70.0) |

0.006%

(60.0) |

0.003%

(30.0) |

0.003%

(30.0) |

0.004%

(40.0) |

0.120%

(1200.0) |

Values in brackets are in parts per million (ppm). Note that 1 ppm is equal to 1 mg per kilogram of sample. To convert to % from ppm – multiplication by 0.0001.

In the table, 30.08% of Fe203 means that there was 300.8 grams of iron per 1 kg sample of ore. Similarly, 59.09 % of Fe203 means that there was 590.0 gms of iron in 1 kg sample of slag. However, 1 ppm is equal to 1 mg per 1 km sample. This means that in the table 70.0 ppm of Cu had 70 mgs of copper per 1 kg sample of ore. This interpretation is true for the rest of the figures in the table.

The format of the responses is that 8 out of the 10 questions required brief answers. (see Appendix for questionnaire). Two required so much detail that

the researcher was free to formulate appropriate follow up questions. The translation from Tumbuka to English is hard as English equivalent of Tumbuka

terms do not exist in certain cases. In such instances the meaning of the Tumbuka word can be found in the key in the appendix of the report. The responses from the respondents were carefully compiled as shown.

1, 2) “Iron smelting existed among the Tumbuka/Cewa particularly in the three localities before the arrival of the white man; Manyara Village, Kapichila Village and Engangeni Village. (see fig. 2) In Manyara Village, there was a Jombo Mtonga and a Kabuskasonde Myirenda; both of these men brought iron smelting in the area. Originally, these men migrated with their parents from Northern Malawi in Mzimba district around Marangazi area. There was scarcity of land in Nyasaland (Malawi) in Marangazi at that time. This is why these people moved in search of land and they settled at Manyara in Lundazi district bringing with them the iron smelting skill.

The Tumbuka brought the iron smelting skill among the Oewa of South-Eastern Lundazi around Kapichila Village (see fig. 2). The people who knew the skill around Engangeni Village in Chief Phikamalaza’s area were a Mcoca, a Cinthula and a Kazengela. But it is not known where these people brought the skill from.

3. The Tumbuka individuals who smelted iron had very good lives entertaining thoughts on how to improve tools with which to work in the gardens. Eventually, they smelted iron from which they made hoes for use in the gardens. This was even before the white men brought their hoes. They were ordinary Tumbuka people with Tumbuka parents. The hoes made from the smelted iron were not meant for marrying more wives or getting rich. They were made because of the necessity to produce more food. The people who made hoes did not have the highest social status. But a MOOCA who was an iron smelter in Engangeni Village area was formerly a major Village Headman before he migrated from Nyasaland. Occasionally the son or grandson of a royal family would also acquire the skill.

4. The difference between villages which had hoes and those which did not have was there. People in villages in which nobody possessed the skill of iron smelting used to take chickens and walk long distances to barter them with hoes, at whatever village they were being smelted. However, some people still used sticks made from Mphengala trees to work with in the garden. In certain cases particularly among the Cewa around Kapichila Village, those who did not have hoes were given some. The difference in crop yields between those who had hoes and those who did not have them should be obvious. But it is difficult to tell because even among people with hoes they have different amounts of crop yields.

5. During this period, after crop harvest the people used to rest as has always been the case in the dry season. During the same time many people used to also go and assist in iron smelting and hoe making. Nshima used to be eaten there. They would be there until dusk. During this period, the people used the time for preparing gardens for next season, they used to go hunting game, drinking beer and thatching roofs.

6. The young people were taught how to smelt iron and make hoes. Some young people would pick up the skill and others would not. They used to assist in working the bellows. (Kubvututa) women who had their monthly period were not allowed to be or work at the ng’anjo site. Women who had their monthly period would spoil the smelting. The women used to assist in drawing water.

7. Iron smelting had a positive effect on the life of the people. It was a source of iron implements like hoes, axes, knives and spears. The hoes were also used for dowry in marriage.

8. The process of iron smelting was that in the very beginning they used to collect clay soil from an ant-hill, water and mix it. In Kapichila area, they used to mix the clay with some charms or medicines while they were saying some incantations. They prayed to spirits so that they should be successful in the iron smelting. They also put medicines in the ng’anjo before putting Makhalang’anjo into it. Then they would begin building the ng’anjo at an appropriate site which was at the bottom of an ant-hill. The ng’anjo was shaped like a small hut; large at the bottom and narrower at the top. Small vent holes were located around the base of the ng’anjo. The ng’anjo was usually built to just beyond an average man’s height. Because the ng’anjo was taller than an average person, scaffolds and supports were built around it. The scaffolds were used to put into it the charcoal and Makhalang’anjo. The supports were for preventing it from collapsing and injuring people. When the ng’anjo structure was built they used to wait until it was dry. Around Kapichila area, they used to burn or roast it until it was cooked. 1 In Manyara area, when the ng’anjo was dry, bakacucutanga. 2 When the ng’anjo was ready the ore was collected. It was known as Makhalang’anjo around Manyara area, Bvimasakalawe around Kapichila and Thale around Engangeni area. The whole village assisted in the smelting of the iron. Beer and food used to be provided at the site.

The next stage was to find Makhalang’anjo. These were sometimes found on a site which a village had abandoned or moved from many years before. (Site known in Tumbuka as Manghuba). But usually Makhalang’anjo could be found anywhere. When the site is located, they used to dig them out of the ground selecting the good quality only. The heavier the better. Sometimes Makhalang’anjo can be found in a Dambo. This was the case in Engangeni area where they dug it from Dembos.

The Makhalang’anjo was collected in large amounts and heaped beside the ng’anjo. Charcoal was also collected in large amounts. Then the two, Makhalang’anjo and charcoal would be placed inside the ng’anjo in alternate layers one on top of the other until the ng’anjo is full. Then fire would be inserted

in the ingredients. Using goatskin bag bellows (Bvukuto) the people would begin blowing air into the ng’anjo from the bottom vent holes. The bellows used to be 6-10 depending on the size of the ng’anjo. Then after blowing for some time, there was red hot fire melting the Makhalang’anjo. In the description of the respondents:

“Sono kuyanba kumabvukutira M’ng’anjo ija, moto uyaka M’Kata M’ng’anjo muja vimakhala ng’anjo bvikupya. Bvikati vapya vija m’ng’anjo yayambaso kunya.”

(Chewa – Tumbuka) Kapichila

“Then you begin blowing the bellows in the ng’anjo. The fire begins burning the makhalang’anjo. When these are burned, the ng’anjo begins excreting.”

_______________________

“Bakapalanga moto kukaya nakuluta nawo nipera bakububika pa chanya pa mathathwe nipera bayamba kubvukula – kubvukuta. Nipera wayskana nabvimathanthwe bvira moto wakatiti unandi comene……Ng’anjo yayamba kunya.”

(Tumbuka) Manyara.

“They used to get fire from the village. They put this fire inside the ng’anjo on top of the mathanthwe. Then they would begin blowing with bellows. There would be big flames of fire burning the thanthwe……Then the ng’anjo would begin excreting.”

_______________________

“….kusonkhela waka, Muthilemo makala, moto ukhale wolilima lilima kose, sono mwaona vyafuma vyati tunkhe tunkhe sono muhamba pakhomo pala cikuni wee……….pesee…… Mukuona hoo yangha ng’anjo.”“…..you add more charcoal into the fire in the ng’anjo, so that there are big flames of fire, then you will see the molten liquids protruding then you poke them with a stick……it pours out……then the ng’anjo will have excreted……

_______________________

These quotations vividly reflect what could be termed the climax of the iron smelting. After blowing the bellows for sometime, a stick was wedged or poked into the bottom hole. Then the molten liquid gushed out of the ng’anjo and solidified as it cooled. When the molten liquid has flowed out, a chunk of iron was removed from inside. The whole process was initiated again. Each time retrieving a chunk of iron. The molten liquid which would be the slag equivalent was known as “Mabvi” and the process of the liquid gushing was termed “Kungha” which in English is excreting. The piece of iron retrieved was known as “Cuma”.

There are times when the ng’anjo did not produce Cuma. In the words of one of the respondents:

“Musanga yabukukula waka tilije to lamo kanthu ca, caukula cing’njo mutaya vyose vila kuthengele taye taye. Mwaona ivi vyati bii apa nkhutaya kula.”

(Tumbuka) Engangeni

They used to say the ng’anjo has vomited and you would throw away everything from it.

These pieces of Cuma were taken to another site for further processing. This site was known as Ciramba or Luvumbo. This is where using goatskin bags again as bellows, the Cuma was put in the fire again. Using special hammers, they made hoes, knives, axes, and spears out of the Cuma. The hammer which they used was known as nkhama in Kapichila. It used to be a stone which looked as round as a chicken’s egg. The hammers do not exist any longer. The pieces of Cuma could also be kept to be made into any implement at a later time.

9. Respondant 1:

It is doubtful whether people could revive or resume iron smelting although it is an easy process. Some of us cannot afford to buy these modern

hoes because of lack of money. If it was well organized around Manyara I am certain it would still work.

Respondent 2:

People would smelt iron if they were forced to do so. But because we inherited the British tradition, this is why not even a single person would dare smelt iron like it used to be done in the old days.

Respondent 3:

It would not be possible these days because there is disintegration. If you asked individuals to come for iron smelting they would refuse saying you are wasting their time because they have been or are used to modern European things.

DISCUSSION

The laboratory analysis of the ore and slag suggest a number of interesting issues regarding iron smelting in the area. The immediate one is that the presence of 300.8 gms of iron per 1 km sample of ore is extremely good for prospects of industrial iron smelting. This was also the opinion of a few chemists and Engineers from the University of Zambia. Further technical confirmation would be necessary in this regard. One encouraging point to be noted is that the analyzed ore was just collected from the surface of the ground while respondents indicated that a better grade ore can be found underground. The presence of 590.9 gms of iron in 1 km sample of slag suggests that the method of iron smelting which has been documented was poor in terms of extraction of iron from the ore. This must have contributed to the high amount of human labor required during the smelting.

As for the other minerals like Copper, Cobalt, Manganese, Zinc, shown in the table, their presence in smaller proportions if hardly a constraint to smelting them. For example, according to the analysis in the table, in every 1 kg sample

of ore there is 0.007% of Cu and 0.120% Mn. Therefore in 1 metric ton (1,000,000 kgs) of ore there would be 70 kg of Copper and 1,200 kg Manganese. The point to be noted, however, is that Copper and Manganese would be side products of iron ore mining and attempting to extract other minerals from the iron ore mining operation would be worth the effort if cheap extraction methods are employed.

The data suggests that iron smelting seems to have spread from Northern part of Malawi to the Lundazi district through the migration of the Tumbukas from that part of the country. It would, therefore, be useful to find out the prevalence of iron working throughout the province with the view of determining whether in-fact it spread from North to South and also whether there were marked differences in methods of smelting due to further innovation, cultural and ecological differences. Out of the many interesting aspects of the results is that the term “Cuma” among the Swahili of Tanzania refers to iron. The same term among the Tumbuka was used to refer to the smelted iron. In contemporary times Tumbuka used the term “Cuma” to mean “Riches”. The linguistic similarity might mean that the skill spread from Southern Tanzania or it might mean nothing beyond the sharing of similar linguistic roots since Swahili and Tumbuka have many words in common as Bantu Languages.

The social organization and consequences of smelting reflect the fact that it was very labor intensive, entire villages had to help; men, women, and children. It is amazing, however, for such an important skill in the lives of the inhabitants, (as far as food production is concerned), that the data suggests that, it was not exclusive: it did not exclusively belong to the realm of royal families, rich individuals with many wives. The transmission of the skill seems to have been done in an open system of take it or leave it. The young watched as the elders smelted the iron.

The process of iron smelting itself reveals that most of the concepts used to capture it are derived from the digestive system. The respondents consistently used the terms Kubukula, Kungha and Mabvi. Kubukula means vomiting which referred to when the ng’anjo failded to “yield” iron. Kungha, which means excreating referred to the process of molten liquids gushing out of the ng’anjo. Mabvi which means feces referred to the slag from the ng’anjo. These concepts perse would perhaps reflect an obsession with disgusting human bodily functions. But further examination would perhaps reflect something different, deeper, and more significant.

Since iron smelting might have been a very significant technological break- through, compared to the use of sticks for farming, the only terms they could use to reflect such a significant process were from the powers of the human body which they were more acquainted with and perhaps better understood. It would not be surprising if in certain parts of Africa terms from child birth were used.

Cook 13 documented iron smelting among the Manyibi of the Matopo Hills of Zimbabwe (Rhodesia). It seems iron work was surrounded by more taboos than in Lundazi. The women, for example, carried the ore in baskets from the surrounding hills. Only girls before puberty and women beyond child bearing age were allowed to do the carrying of the iron ore. However, the women were only allowed within 30-40 feet of the furnace. There are several similarities between the two areas; the hoes were used for lobola, the skill was not necessarily handed down from father to son. Any man could learn it who was strong enough. Similarities in linguistic terms further suggest a common source of the skill.

ENGLISH MATOPO HILLS TERM LUNDAZI

Furnace Izghamba Ng’anjo

Bellows Mvuto Bvukuto/Luvumbo

Blow pipes Donje —-

Ash Ulota Vyoto/Milota

Slag Manyere Mabvi

Charcoal Masimbe Makala/Masimbe

Another method of iron smelting is the one which was documented by Todd14 in Ethopia among the Dimi. This is known as the bloomer process. Every aspect of the method is more or less identical to the method which was used in Lundazi except that the Dimi did not remove the slag from the smelted iron.

What is the possible relationship between traditional iron smelting and appropriate technology? Appropriate technology can be looked at from three possible perspectives: (1) the national technology or massive economy perspective, (2) the intermediate perspective, and (3) individual perspective. The national technology approach usually has the objective to raise the standard of living and create jobs for a vast majority of large national population. This is irrespective of whether the whole technology, including personnel, is imported. Most of the third world nations follow this approach.

The intermediate perspective usually advocates the use of in-between technology. This could be likened to the use of a motorcycle with the psychological comfort that it lies between a bicycle and a car. This perspective ignores the fact that even though the technology might be in between the essential ingredients of mastery and control is still missing.

The individual perspective focuses on what technology can be adopted by an individual and is the perspective which is the most useful in terms of the role of the knowledge of traditional iron smelting can play.

Carr15 discusses some aspects of appropriate technology:

The most immediate need is obviously that of the provision of millions of new work places, with the majority being created in the rural areas where 80 to 90 percent of the population of the developing countries still live. Continued dependence on capital – intensive technologies imported from the West is unlikely to provide more than a fraction of the work places needed. On the other hand, traditional techniques, while having a very high labor requirement, are characterized by very low capital and labor productivities and do not generate the surplus needed for rapid growth in capital stock. This has led to the suggestion that what is needed are technologies which are “intermediate” between these two extremes.16

The idea is that a project at the intermediate level of technology would cost K300 as opposed to K3000 with high technology and K3 with traditional technology. The only excruciating problem is that the complexity of technological development in third world countries defies any solution short of one which is based on the ability of people to command and control the technology. So long as everything continues to be imported, improvement in the standard of living will be lopsided or a mere flicker in the pan. To achieve some permanency, appropriate technology must be technology which can be absorbed, assimilated, accommodated, and appropriated by individuals in a specific society. This happens (or is done) in such a way that the individuals concerned have mastery and control over technology and do not harbor attitudes of mysticism about it. Extensive knowledge of traditional iron smelting could enhance or initiate these attitudes towards technology. The more mere knowledge that iron is extracted from stone would be illuminating. The practical knowledge that it can be made into implements and gadgets like hoes, ploughs and bicycle parts, would further remove the mysticism that even the simplest technology currently creates. Only in the sense that people can control, understand, or appropriate the technology can it be truly termed “appropriate technology”.17

Enhancement of the appropriation of technology can be achieved for example, by teaching in schools the traditional iron smelting process in theoretical and practical terms. The advantages, qualities, and social organization of iron smelting in the traditional context could be frankly discussed. The classroom material on traditional iron smelting of the current types can hardly be expected to be useful since they often are riddled with colonial biases. For example, one of the Teacher’s Handbooks for social studies discusses traditional iron smelting.

“This was a sedimentary deposit which had been laid down along stream edges and in Dambos and which could be used to make poorer quality iron.”18

This statement is not followed by how and why. Therefore it gives the suspicious reflection to school children that the indigenous iron was inferior. Kjekshus19 suggests that the indigenous iron was superior over the type brought by colonialists because the former was not brittle and therefore the hoes and other implements did not crack as opposed to the imported iron at the time.

Finally, the field work did not exhaust the inquiry into all aspects of iron smelting. For example, precise information could be collected on the duration of iron smelting, how many times each ng’anjo was reused. Also the social organization surrounding iron work needs further work. For example, what were the nature of songs, rituals, and prayers conducted. For example, a (cow-like) skeleton of a head of an animal found near an iron smelting site near Engangeni Village suggests that perhaps certain sacrifices were made at the iron smelting sites. Technical indigenous terms for the entire process could be inquired into more deeply by increasing the sample of respondents from various parts of the district.

CONCLUSION

The objectives of the research were to analyze slag and ore samples to document the exact procedure of traditional iron smelting in Lundazi District, the social organization which surrounded the iron work, its historical source, and its implications on appropriate technology. The findings reflect components in the ore and slag, the exact procedure of iron smelting process and the technical terms, the work was very labor intensive demanding participation of an entire village, some taboos prevailed and iron smelting was not the activity of only exclusive classes or individuals. Iron work seems to have spread through in migration of ordinary individuals from Northern Malawi (Nyasaland). The possible contribution or role of traditional iron smelting knowledge could pay in appropriate technology is discussed in theoretical as well as practical terms. Suggestions are advanced regarding aspects of iron work which could be the focus for a further study.

ENDNOTES

- East Africa constitutes of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Central Africa is comprised of Zambia and Malawi while Southern Africa constitute of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Bostwana, and South Africa. The colonial names for the countries which changed their names since their independence are: Tanzania used to be Tanganyika, Zambia was Northern Rhodesia, Malawi used to be Nyasaland, Zimbabwe was Southern Rhodesia and Bostwana used to be Bechuanaland.

- Brian M. Fagan, (ed.) A Short History of Zambia. From the Earliest Times Until A.D. 1900, London, Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Ibid., p. 82.

- Ibid., p. 82.

- Ibid., p. 82.

- Judith A. Todd, “Studies of the African Iron Age,” Journal of Metal, November 1979, pp. 39-45. The radio carbon dating map of Africa is reproduced from the same Journal by the Geography Department of the University of Zambia.

- J. A. Todd and J. A. Charles, “Metallurgy as a Contribution to Archeology in Ethiopia.” (Journal Unknown), pp. 31-41.

- Ibid. p. 35.

- Judith A. Todd, “Studies of the Africa Iron Age,” Journal of Metal, November 1979, pp. 39-45.

- G. Quick, Doctor Ironstone (Danga ya Lubwe): A Study of the Smelting and Smithing Methods of Bena Chisinga of Northern Rhodesia, 1947, M. Sc. Thesis, university of Wales.

- C. K. Cooke, “Account of Iron Smelting Techniques once practiced by the Manyibi of the Matopo District of Rhodesia, The South African Archeological Society, June 1966, Part II, Vol. XXI, No. 82, pp. 85-86.

- A Copy of the Questionnaire can be found in Appendix.

- C. K. Cooke, “Account of Iron Smelting Techniques Once Practiced by the Manyubi of the matopo District of Rhodesia, The South African Archeological Society, June, 1966, part II, Vol. XXI, No. 82, pp. 85086.

- Judith A. Todd, “Studies of the African Iron Age,” Journal of Metal, November 1979, pp. 39-45.

- Marilyn Carr, Economically Appropriate Technologies for Developing Countries: An Annotated Bibliography, Intermediate Technology Publications, 1976.

- Ibid., p.7.

- Philip Kingsley, “Technological Development: Issues Roles and Orientations for Social Psychology,” September 1980, University of Zambia. This paper discusses in convincing detail the concept of “Appropriation” of technology 1976.

- Marilyn Y. Jones, Producers and Traders in the Zambian Past, Historical Association of Zambia, Teacher’s handbook, NECZAM, LUSAKA, 1979.

- Helge Kjekshus, Precolonial Industries: A Preliminary Survey (Manuscript)

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carr, M. Economically Appropriate Technologies for Developing Countries: An Annotated Bibliography, London, Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd.

Cooke, C. K. “An Iron Smelting Site in the Matopo Hills,” Bulletin of South African Archeological Society, Vol. XIX.

Cooke, C. K. “Account of Iron Smelting Techniques Once Practiced by the Manyubi of the Matopo District of Rhodesia” South African Archeological Society Bulletin, Vol. XXI, Part II, No. 82, June 1966, pp. 85-86.

“The Kalomo/Choma Iron Project (1960-3): Preliminary Report, South African Archeological Society Bulletin, Vol. XVIII, No 69, April 1963, pp. 3-19.

Fagan, B. M. (ed) A Short History of Zambia, From the Earliest Time Until A. D. 1900. London, Oxford University Press, 1966.

Howes, M. “The Uses of Indegenous Technical Knowledge in Development”, I. D. S. Bulletin, January 1979,

Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 12-23.

Fagan, B. M. (ed) A Short History of Zambia, From the Earliest Times Until A. D. 1900, London, Oxford University Press, 1966.

Howes, M. “The Uses of Indegenous Technical Knowledge in Development,” I. D. S. Bulletin, January 1979,

Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 12-23.

Howes, M. and Chambers, R. Indegenous Technical Knowledge: Analysis, Implications and Issues”, I. D. S. Bulletin, January 1979, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 5-11.

Jequier, N. (ed) Appropriate Technology: Problems and Promises,

Paris, 1976.

Jones, M. Y. Producers and Traders in the Zambian Past, Historical Association of Zambia, Teacher’s Handbook, NFCZAM, Lusaka, 1979.

Kjekshus, H. Pre-Colonial Industries: A Preliminary Survey, (Manuscript).

Kjekshus, H. Ecology Control and Economic Development in East African History, Heinemann, London, 1977.

Langworthy, H. W. Zambia Before 1890: Aspects of Pre-Colonial History, London, Longmans, 1972.

Maggs, T. M. OC “An Unusual Implement and Its Possible Use,” Vol. XXI, The South African Archeological Society, Vol. XXI, Part I, No. 81, March, 1966, pp. 52-53.

Patridge, T. C. “A Middle Stone Age and Iron Age Site at Waterval, North West Johannesburg,” Bulletin of the South African Archeological Society, Vol. XXI, Part IV, No. 76, December, 1964, pp. 102-110.

Philipson, D. W. “The Chronology of the Iron Age in Bantu Africa,”

The Journal of African History, Vol. XV, 1974,

No. 1, pp. 1-26.

Ponsnansky, M. “Iron Age in East and Central – Points of Comparison.” South African Archeological Society Bulletin, Vol. XVI, No. 64, December 1961, pp. 136-138.

Sasson, H. “Early Sources of Iron in Africa.” South African Archeological Bulletin, Vol. XVIII, No. 72, December 1963.

GLOSSARY OF SOME TUMBUKA CONCEPTS

BVUKUTO Bellows made of goatskin bags; also “Luvumbo”, the site where the axes and hoes were made from the smelted iron.

CUMA Riches; also “Usambazi”; to be rich.

DAMBO An area which is wet with green grass; sometimes it is swampy. It is often a source of a stream or river.

KUOCHA To set afire.

KUPYA To be hot; also to refer to being cooked.

MABVI Feces; also uncommonly used to refer to something bad.

MAKALA Charcoal.

MAKHALANG’ANJO The equivalent of ore; variously termed as “Thale” “Masakalawe”.

NG’ANJO Kiln, Furnace.

NKHAMA Hammer used in traditional times.

KUBUKULA To vomit, “Yabukula” it has vomited.

YANGHA It has excreted; “Kungha” to excrete.

“A” Before a name is used as respectful address, “A” pronounced as in Pat or Ham.

NSHIMA Staple food cooked from maize flour.

THE UNIVERSITY OF ZAMBIA

INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES

TITLE:

PROCESS OF TRADITIONAL IRON SMELTING IN EASTERN ZAMBIA AND ITSPOSSIBLE IMPACT ON APPROPRIATE TECHNOLOGY

MWIZENGE S. TEMBO

RESEARCH FELLOW

TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY RESEARCH UNIT

DECEMBER, 1981

***My grandfather, Zibalwe Tembo, was a famous headman of Zibalwe Village and a well known iron smelter. I was inspired to conduct this original research in an effort to document this skill that my ancestors had mastered in the mid to late 1800s before the arrival of British colonialism. November 12, 2010

[AUTHOR B.A. University of Zambia, M.A. Michigan State University. Currently Research Fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Zambia, Lusaka. 1981

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

My regards to the following for their help in this project; UNICEF in collaboration with the Ministry of Youth and Sports of the Republic of Zambia for indirectly sponsoring the study; Professor Serpell, the Director of the Institute of African Studies for his comments and suggestions, Mrs. Mwacalimba for the typing and Dr. Daka of the Chemistry Department of the University of Zambia for his assistance in the interpretation of the chemical analysis of the field samples. My thanks to Jane Myers who is Bowman Hall Secretary at Bridgewater College. She retyped ( in November 2010) the old faded manuscript from 29 years ago in 1981.]