by

Mwizenge S. Tembo, Ph. D.

Professor of Sociology

Introduction

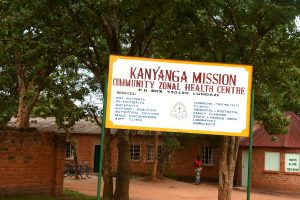

The hot day was seething with dry heat in the summer of Savannah Zambia in Southern Africa in August 1964. My father, mother, my brothers, and sisters were worried. There was tension, sadness and anxiety in our Tembo family of 9 children. For days we did not know whether we would see our second oldest 15 year old sister alive. We were a family of nine; 3 brothers and 6 sisters. For days there was news on the radio and many rumors that a religious war had broken out in our home district west of Lundazi including my mother and father’s Chipewa and Seleta villages. May be over a total of six hundred people in our two villages alone may have been burned in their grass thatched houses, killed, and massacred. Our sister Misozi (not her real name) at the time was attending Kanyanga Catholic Mission Boarding School which was right in the heart of the religious war. That school was about ten miles from our two villages. The tension was unbearable as we waited every day for what seemed

like days on end.

On that hot day in August that I will never forget; the glowing red sun was setting as the family was sitting in front of the house. Someone said: “I can see something coming up the road; there is someone”. We all saw a small figure bop its head up and down on the Western horizon from Chipata-Lundazi Road coming toward our house. As the lone figure drew nearer, we the children screamed first:

“It’s sister Misozi!!!” as we ran to greet her and hold her hands. She looked haggard and had a weary smile on her face.

Misozi was ragged, her face unwashed and her hair shaggy and dirty. She had not had a bath for days. She had dusty bare feet and had just walked 5 miles from the main road. She was only wearing a dress and a chitenje cloth draped over her small shoulders. She literally had only the clothes on her back. As a child the best part about my sister Misozi’s safe return was to see the utter joy and relief on my parent’s faces; their baby was alive. As a Zambian or African family, we quickly conducted the malonje greeting custom. This is when the host greets the guest and the guest gets to explain the details of the purpose of their visit. This is what the whole family heard from my older sister Misozi.

All the converts of the new Lumpa Church for weeks had gathered at Kamtola headquarters in the Northern Province near the town of Chinsali. They had decided they would kill all the non-believers in all the villages. The small clinic at the Kanyanga Catholic Boarding School for weeks was overwhelmed treating those wounded in the war who were brought in by the truck loads. Thousands had already been killed. As the war drew nearer to the school, the Northern Rhodesia British Colonial government sent 4 buses to the school with armed battalion soldiers to evacuate the school. My sister and her school mates hastily boarded the buses under heavily armed soldiers. Some soldiers rode inside the buses and some were located on top of

the roof tops of the buses. No student was allowed to bring anything besides what they were wearing. My sister tried to find her shoes in the dormitory. She was ordered at gunpoint to hurry out of the dorm.

Significance of Inferfaith Unity

This is a rather dramatic introduction to the topic of interfaith. This is a very vivid example of the extreme of what can happen when either interfaith does not happen or religious groups become intolerant. It need not always result in murder and violence. But it has happened in history, it is happening now, and it probably will happen in the future if people of different faiths do nothing in the presence escalating religious tensions, hostility, and violence. In this presentation, I want to discuss FOUR specific aspects of the positive aspects of living the interfaith mission in life. The first is family attitude, second, the attitude of community and the religious faith itself. Third, the policies of the government regarding the interfaith mission. Fourth and last I will answer the question: “Is the interfaith mission the solution to religious tensions, hostility and unfortunately violence?”

The Family and Interfaith Mission

Our attitudes about religious differences within our Zambian or African family may have been influenced by a long cherished social value that is taught and expected in all brides and grooms as they are about to get married. Older women advise the bride that if your husband likes a particular food that you yourself might dislike or might not care for, cook that food very carefully and serve that food to your husband with respect and joy. In the same way, older men advise grooms that if your wife likes a particular food even if you dislike the food yourself or might even hate it, get it for her. Give that food to her with respect and joy. Your wife, so the grooms are advised, will love you forever. This might apply to how we treat or respond to different religions that might exist in our communities: you may dislike how they pray, or what God they say they pray to. But you should always respect how other people pray or their religions. That’s the best way to create interfaith peace and harmony.

My family of 9 and I must be the luckiest people in the world. My parents took us to and encouraged us all to attend church. They were comfortable with all of us belonging to different churches including some who might not have been as religious. We all respected each other, were tolerant and my parent made sure that happened. I attended a Dutch Reformed Church Boarding School for 3 years between the age of 11 and 13. My 2 older sisters belong to the Catholic Church. My younger sister belongs to

a Pentecostal church. One of my brothers joined the Islamic faith. My parents never expressed religious zealotry or never insisted on religious purity like the early Puritans on the East Coast of the United States. Religious zealotry and purity which certain forms of religious fundamentalism that they exhibit may be antithetical to the interfaith mission.

Attitude of the Religious Faith

The attitude of the religious faith itself may determine whether its members can practice or fulfill the interfaith mission. Is the religion tolerant of members of other religions or non-believers? This is the toughest question because it gets to the heart of whether people of different faiths and religions can live together as neighbors, school mates, and as community members with minimal or no religion-based tensions and conflict.

Even though the edicts of the religion may endorse members avoiding, shunning, ostracizing and even harming people who belong to other religions or non-believers, can religious peaceful coexistence still be maintained? Again my answer goes back to the beliefs and experiences within my family. The family is the first line of defense or mitigating the negative or hostile religious attitude. When a child, a parent, or other family members say negative things about someone belonging to another different religion from their own, it is up to parents and family members to object loudly to the negative behavior. Whenever any of my siblings or myself said anything negative about people from a different religion or different culture, my parents were the first ones to discourage that behavior.

My parent’s words always echo in my mind. They would say in Tumbuka language:

“Iwo para opemphera nthana bakwanangila vici iwe panyake ise pa banja pithu? Yayi, kanawo ndimo wopempherela. Kuli chikatolika, Chitawala, Chi Slam.”

Translated as: “So, if they pray like that, how do they hurt you or us as a family? No, don’t say such negative things. That’s the way they also pray. There are Catholics, Watch Tower Church members, and Muslims or Islam.”

I am not here saying this is easy may be in the face religion based provocation, hostility, violence or even murder. I often ask myself how do those people who live in difficult religious hot spots live their everyday lives? I am referring here to Muslims and Christians in Northern Nigeria, for example, who frequently have violence flaring up resulting into horrendous violence and murders. I don’t know how they did this and why it happened that way. But after the Lumpa religious war ended, many surviving former members returned to the villages in Lundazi. Some of them were my kinship relatives. There was forgiveness and quiet reconciliation and no reprisals at all up to this day in all the villages.

Government Policies

Government policies can set the tone for interfaith peace, coexistence, and religious tolerance. Despite the rough start of the country’s independence in with the Lumpa Church religious war in October 1964, Zambia was a non-racial, multiethnic and multi-religious society. The President of the country and the top political leadership always emphasized freedom of religion and peaceful coexistence of not only people from different racial, ethnic, and racial backgrounds but also accepted religious diversity.

My country of Zambia is the size of Texas and has a population of 14 million. It has 27 so-called tribes or more accurately ethnic groups because “tribes” no longer exist in Zambia and much of Africa.

“Zambia Christian denominations are mainly Protestant and Catholic and include Anglican, Pentecostal, New Apostolic Church, Lutheran, Seventh-day Adventist, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Branhamism, and a variety of Evangelical denominations. Christianity so dominates the country that some reports suggest that an estimated 85% of the population belongs to some form of Christianity, another 5% are Muslim, 5% other faiths, including Hinduism, Bahaism, and traditional indigenous religions, and 5% are atheist.” (Tembo, 2012, p. 183)

It seems a successful interfaith mission not only depends on the community living a positive life of cultural diversity but it ought to live a life of active cultural integration. Zambia is so lucky because it might be the most well ethnically integrated society in the world. This is no hyperbole or exaggeration. So it might be more accurate to say that my home country of Zambia has peaceful religious coexistence because the government and political leadership actively implemented the social integration of the so-called 72 tribes or ethnic groups within the context of a non-racial society.

“Is the interfaith mission the solution to religious tensions, hostility and unfortunately violence?”

My response to this is rather nuanced. It may not even be what you might expect. I would like to thank the Harrisonburg Interfaith Association for the great work they are doing to create harmony, unity, and reconciliation among the various religious faiths in the community. May be we could talk about this in the question and answer time. If a community and society has already established the 3 factors I have just talked about, there may be no need for a formal an interfaith mission of organization. If families live with people from different faiths, communities, schools, clubs, and neighborhoods live with people of different faiths, and lastly if the government and political leaders already espouse the virtues of people from different religions living together; then the formal interfaith mission organizations become icing on the proverbial cake. Let me elaborate on this.

Conclusion

A successful Interfaith mission in all communities or societies start with families that actively encourage and live the mission in their homes. This is where we should pause and ask: “Is the Harrisonburg community living the Interfaith mission? Is America as a society living the Interfaith Mission?”

A successful Interfaith Mission in all communities or societies start with the different religions themselves actively encouraging and living the Interfaith mission in their congregations in churches, Synagogues, Mosques, and elsewhere. We can ask the same question: “Are Harrisinburg City and churches in the surrounding counties living an interfaith mission among their congregation in churches, Synagogues, Mosques and where ever they worship?”

A successful Interfaith Mission in all communities and societies start with government and political leaders actively encouraging and living the Interfaith mission among all the diverse religions within the country. “Is the American government and the political leaders encouraging the Interfaith Mission in the entire country?”

Before I end, let me share with you the song that I sung with my first grade classmates during a Religion Knowledge period in 1959 in my home village school in Zambia in Southern Africa in 1959.

Leader: Adam, Adam

Response: Adam na Eva (Twice)

Response: Njinjola chikulu chikamnyenga Adam, Adam na Eva.

Translation: A big snake tempted Adam, Adam and Eve.

Thank you

The address is also available here Prof. Tembo Addresses the Interfaith Gathering.