Introduction

Humans today have at their disposal dozens of both domesticated and wild fruits. These include oranges, apples, pawpaws, guavas, pineapples, cherries, strawberries, mangoes, kiwi, bananas, grapes, pears, peaches, and many other domesticated but less well known fruits all over the world. Some of the wild fruits found in Zambia and perhaps elsewhere in tropical countries in Africa include, masuku, mbula, mbulumbunje, futu, kachele, nchenja, kasokolowe, matongo gha kalulu, matowo, nthumbuzgha, mazaye, kabeza, msekese, chigulo, and many others. Among all or most of these fruits, the mango has to be the best and most delicious fruit. This article describes the mango fruit, how it is grown, its significance as a strictly seasonal food in Zambian and perhaps African culture.

Humans today have at their disposal dozens of both domesticated and wild fruits. These include oranges, apples, pawpaws, guavas, pineapples, cherries, strawberries, mangoes, kiwi, bananas, grapes, pears, peaches, and many other domesticated but less well known fruits all over the world. Some of the wild fruits found in Zambia and perhaps elsewhere in tropical countries in Africa include, masuku, mbula, mbulumbunje, futu, kachele, nchenja, kasokolowe, matongo gha kalulu, matowo, nthumbuzgha, mazaye, kabeza, msekese, chigulo, and many others. Among all or most of these fruits, the mango has to be the best and most delicious fruit. This article describes the mango fruit, how it is grown, its significance as a strictly seasonal food in Zambian and perhaps African culture.

The Mango Fruit

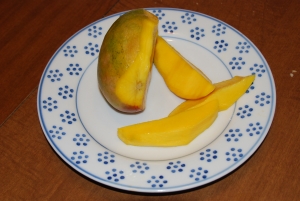

The Mango fruit is generally oblong and the average size of a fist and very dark green when mature and unripe. When the fruit is ripe it is generally bright yellow to red and some have patches of green and yellow when ripe. Some of the mangoes remain green when they are ripe. The only way you would be able to tell they are ripe is if you press your finger on the fruit known as kutofya. It is soft then you know the Mango is ripe. Because the Mango fruit has been subjected to virtually no commercialization for the most part, it has a wide variety of types. There are 2 extreme types of Mangoes; there are the large big type of Mango known as Dudu in Eastern Zambia and on the other extreme are the smallest variety. In between there are dozens of types of Mangoes.

The Mango fruit is generally oblong and the average size of a fist and very dark green when mature and unripe. When the fruit is ripe it is generally bright yellow to red and some have patches of green and yellow when ripe. Some of the mangoes remain green when they are ripe. The only way you would be able to tell they are ripe is if you press your finger on the fruit known as kutofya. It is soft then you know the Mango is ripe. Because the Mango fruit has been subjected to virtually no commercialization for the most part, it has a wide variety of types. There are 2 extreme types of Mangoes; there are the large big type of Mango known as Dudu in Eastern Zambia and on the other extreme are the smallest variety. In between there are dozens of types of Mangoes.

The tastes, textures, and aromas have many varieties. Often only people who have eaten dozens of these varieties of Mangoes can distinguish some of the subtle but very significant differences in the taste and texture of the Mango fruit. People will often say you have develop a deeper taste for some foods in order to be conscious of the subtle nuances in their taste. Often people will say you will have to develop a taste for wine, coffee, or tea. It is the same thing with Mangoes; only if you either grew up eating dozens of varieties or you have eaten dozens of different varieties, it may be difficult to experience and fully appreciate the full range of qualities of Mangoes and their varying tastes, flavors, and aromas.

Growing Mangoes

The Mango fruit as eaten today in Zambia, perhaps in most of tropical Africa, and elsewhere has to be a fruit that grows and thrives very well but needs the least human intervention, labor, and resources for it to grow. If you travel in both urban and rural Zambia, you will notice Mango trees virtually everywhere. You can see them in the backyards of homes, in school yards, along streets, around villages, in the wild bush, and especially in fields in which people cultivate crops. Although Mango trees will be trimmed if they obstruct something, no one ever waters them, sprays them with pesticides to kill bugs, no one puts manure or fertilizer around them. It is a fruit that seems to be best adapted to wherever humans live in tropical Zambia. Although there are efforts often for people to plant them, they seems to germinate on their own where ever humans have randomly thrown or deposited their seeds when eating the fruit.

The Mango fruit as eaten today in Zambia, perhaps in most of tropical Africa, and elsewhere has to be a fruit that grows and thrives very well but needs the least human intervention, labor, and resources for it to grow. If you travel in both urban and rural Zambia, you will notice Mango trees virtually everywhere. You can see them in the backyards of homes, in school yards, along streets, around villages, in the wild bush, and especially in fields in which people cultivate crops. Although Mango trees will be trimmed if they obstruct something, no one ever waters them, sprays them with pesticides to kill bugs, no one puts manure or fertilizer around them. It is a fruit that seems to be best adapted to wherever humans live in tropical Zambia. Although there are efforts often for people to plant them, they seems to germinate on their own where ever humans have randomly thrown or deposited their seeds when eating the fruit.

In tropical Zambia, the Mango trees have small white flowers sometime in April and June. The small little fruits are visible on trees by September of each year. In December of each year at the beginning of the rainy season, the fruit reaches its full green maturity. Some of the Mango fruit begins to ripen as early as first week of December and most of it ripens by the third week of December during the Christmas Season. The last of the ripe Mango are during the end of January and beginning of February.

Food Significance

The Mango is not just a fruit but it is one of the most cherished foods in traditional Zambia. While urban Zambians may regard the Mango fruits as something they purchase at the market during December, the fruit is at the center of rural Zambian society as a source of food that is so anticipated and cherished. Europeans and some of those who live outside tropical Africa have established the reputation that the Mango fruit has a purely utilitarian purpose among indigenous Zambians. This reputation has historically created in in the non-African minds that the Mango fruit is purely a food supplement for the otherwise near starving suffering rural Zambian or African dwellers during the hunger season. The reasoning was that the food reserves for the subsistence of the rural dwellers were running low at this time and therefore the Mango provided much needed scarce food during the hunger season. Although there is no doubt that this may have been the case during some specific periods and in some specific geographic locations, this author’s experiences with Mangoes in the village in the 1950s and recently in 2011 may contradict this gloomy picture.

When this author lived in the villages of rural Zambia in Lundazi in the 1950s with his grandparents, he remembers eating and enjoying Mangoes virtually every day during the Mango season. Grandparents and mothers used to prohibit us children from eating Mangoes in the late afternoon, because then we would not be able to eat dinner or supper of the Nshima staple meal. Mangoes are such a filling fruit. At the end of the growing season in early March, my grandparents and virtually all household still had maize and peanuts stored from the previous season still available which they called chomba or old harvest food from the previous season which was usually April of the previous year.

When this author lived in the villages of rural Zambia in Lundazi in the 1950s with his grandparents, he remembers eating and enjoying Mangoes virtually every day during the Mango season. Grandparents and mothers used to prohibit us children from eating Mangoes in the late afternoon, because then we would not be able to eat dinner or supper of the Nshima staple meal. Mangoes are such a filling fruit. At the end of the growing season in early March, my grandparents and virtually all household still had maize and peanuts stored from the previous season still available which they called chomba or old harvest food from the previous season which was usually April of the previous year.

The Mango fruit when it ripens is available in abundance as trees are everywhere such that people casually eat them when they walk by a tree, take some home to store in the house for easy eating as a snack, they eat it in the field after hoeing for a few hours. The aroma of the beautiful Mango ripe fruit is in in the air when one walks by a mango tree, it is in homes, and perhaps even in people’s dreams. Some people who live near urban areas will pick the free Mango fruits in their neighborhood, village, or field in large baskets and take them to the city or town to sell.

The Mango has to be the best fruit because when ripe it is hardly tart, but very sweet. A ripe Mango seems to lend itself easiest to peeling using one’s teeth. There is hardly anything unpleasant to spit out as one peels the mango using one’s teeth and mouth. One can even choose to chew even the skin in certain instances of very ripe Mangoes. One can also very easily use a knife. The sweet juice that sometimes tastes like nectar is so plentiful that it drips down your arm or hands as you take a bite. There is no bitter aftertaste in one’s mouth after eating Mangoes as characteristic sometimes of some fruits. The balance of water and sweetness is so good that you never have to drink water after eating Mangoes. The fiber and the flesh of the fruit are such that they fill you up after you have eaten a few Mangoes. The fiber also acts as good natural flossing of teeth as it is very normal after anyone eats Mangoes, without the use of a knife, to spend some time to pick the fiber off between one’s teeth. Hardly none of the indigenous eaters of Mango ever find this removing of fiber from the teeth to be inconvenient. It is regarded as one of the normal acceptable ritual associated with enjoying the eating of Mangoes. The Mango also enhances digestion as the very active live enzymes and plenty of fiber thoroughly cleans one’s colon virtually every day at the peak of the Mango season which is from December to early February in Zambia.

The Mango has to be the best fruit because when ripe it is hardly tart, but very sweet. A ripe Mango seems to lend itself easiest to peeling using one’s teeth. There is hardly anything unpleasant to spit out as one peels the mango using one’s teeth and mouth. One can even choose to chew even the skin in certain instances of very ripe Mangoes. One can also very easily use a knife. The sweet juice that sometimes tastes like nectar is so plentiful that it drips down your arm or hands as you take a bite. There is no bitter aftertaste in one’s mouth after eating Mangoes as characteristic sometimes of some fruits. The balance of water and sweetness is so good that you never have to drink water after eating Mangoes. The fiber and the flesh of the fruit are such that they fill you up after you have eaten a few Mangoes. The fiber also acts as good natural flossing of teeth as it is very normal after anyone eats Mangoes, without the use of a knife, to spend some time to pick the fiber off between one’s teeth. Hardly none of the indigenous eaters of Mango ever find this removing of fiber from the teeth to be inconvenient. It is regarded as one of the normal acceptable ritual associated with enjoying the eating of Mangoes. The Mango also enhances digestion as the very active live enzymes and plenty of fiber thoroughly cleans one’s colon virtually every day at the peak of the Mango season which is from December to early February in Zambia.

Social and Culture Significance: Mango Stories

The Mango fruit is enormously significant in the social and cultural life of rural Zambians. Children as young as 2 will pick their own ripe fruit from the trees that are around houses, and all over the village or the field. The children like the autonomy of eating a food about which an adult cannot prevent or stop them from getting and eating. Adults try to keep an eye on how much the children have eaten especially late in the afternoon so that mothers do not cook a large nshima staple meal and have it go to waste because the children are too full to eat dinner or supper.

Adults will eat a few Mangoes if they feel like it when they walk past a tree with ripe fruit in the course of doing daily chores especially hoeing in the field. As I travelled by bus from Lusaka the Capital City of Zambia to the remote Lundazi Villages in Eastern Zambia, so many times I saw adults sitting on the ground or a log in the fields eating Mangoes. I knew they were taking a much needed snack, refreshment, or food break as they continued to hoe in the field.

Adults will eat a few Mangoes if they feel like it when they walk past a tree with ripe fruit in the course of doing daily chores especially hoeing in the field. As I travelled by bus from Lusaka the Capital City of Zambia to the remote Lundazi Villages in Eastern Zambia, so many times I saw adults sitting on the ground or a log in the fields eating Mangoes. I knew they were taking a much needed snack, refreshment, or food break as they continued to hoe in the field.

When the Mangoes begin getting ripe, the culture has an accepted communal practice that anyone can walk to any field or Mango tree and pick a few Mangoes just to eat right there and then. The only objection is if someone goes to another person’s field or tree with a large basket to pick up large quantities of Mangoes either to take home or for some other objectionable reasons. Since Mango trees are everywhere, this ensures that all adults and children can have access to the fruits to eat at any time wherever they are during the day. When anyone is picking ripe Mango fruits from a field, the only thing they have to watch for is not to trample the maize, peanuts, and pumpkin crop that may be only a few inches to knee-high at this time of the early growing season. The other objection is to be careful to not accidentally take down plenty of green unripe mangoes in the process of trying to get one ripe Mango. This wastes a lot of Mangoes. The objections to this behavior create childhood Mango stories.

My Cousin Loses His Shorts

When I lived as a child in the village in the 1950s one day during the rainy season, my friends and I decided we were tired of eating the small or little Mangoes. We wanted the bigger tastier Dudu Mangoes. But they were only available from Mr. Ngamira field a couple of miles from our village. The 8 of us boys ranging from 7 to 12 years old decided we would go to the Ngamira field late in the afternoon to eat a few of the Dudu Mangoes. We walked in the winding bush path in a single file to the edge of the field that had just been hoed with beautiful ridges with small or young peanut and maize plants growing on top of the ridges. There seemed to be no one in the field. That’s exactly what we had been hoping for.

We hastily and noisily scampered towards the tree looking for the ripe large tasty Dudu mangoes. When we were about thirty yards from the thick large tree, a green Mango suddenly shot from the tree and landed may be a few feet from me. Before we could figure out what was happening another Mango shot out of the tree and landed a few feet from my cousin. We were under attack. There was a scream to run. We all fled into the path towards our village. My 11 year old cousin Thauro who was running in front of me didn’t have a belt. His shorts fell to his ankles, he tripped and fell exposing his bottom as he quickly stood up pulled up his shorts holding on to them as he continued running. After about half a mile, we all stopped gasping for breath. We began to laugh uncontrollably at my cousin Thauro for tripping, losing his shorts and exposing his bottom.

We hastily and noisily scampered towards the tree looking for the ripe large tasty Dudu mangoes. When we were about thirty yards from the thick large tree, a green Mango suddenly shot from the tree and landed may be a few feet from me. Before we could figure out what was happening another Mango shot out of the tree and landed a few feet from my cousin. We were under attack. There was a scream to run. We all fled into the path towards our village. My 11 year old cousin Thauro who was running in front of me didn’t have a belt. His shorts fell to his ankles, he tripped and fell exposing his bottom as he quickly stood up pulled up his shorts holding on to them as he continued running. After about half a mile, we all stopped gasping for breath. We began to laugh uncontrollably at my cousin Thauro for tripping, losing his shorts and exposing his bottom.

When we returned to the village, we told my grandmother about how something or a creature threw Mangoes and nearly hit us at the Ngamira field when we were looking to eat Dudu Mangoes. Could it have been a man? My grandmother didn’t seem concerned. She said we would have deserved being hit since were probably walking all over ruining Mr. Ngaramira’s young maize crop.

When we returned to the village, we told my grandmother about how something or a creature threw Mangoes and nearly hit us at the Ngamira field when we were looking to eat Dudu Mangoes. Could it have been a man? My grandmother didn’t seem concerned. She said we would have deserved being hit since were probably walking all over ruining Mr. Ngaramira’s young maize crop.

Dangers of Mango Hunting

In the late 1960s when I lived in a rural area north of Chipata in Chief Mshawa’s area, I had an experience that I will never forget. My cousin and I were both 14 years old. We decided we would wander far from our own field in search of even newer, fresher, better and sweeter Mangoes. We must have walked a couple of miles beyond our familiar grounds, when we found this very large tree with beautiful large yellow ripe Mangoes. As were nervously maneuvering around the tree to spot the best looking ripe Mangoes, a fierce looking man with a thick beard and wide eyes suddenly emerged out of the nearby bushes on the edge of the field yelling:

“Hey!!! You!!! What are you doing trampling my maize and eating my Mangoes!!” He was wielding an axe.

“Hey!!! You!!! What are you doing trampling my maize and eating my Mangoes!!” He was wielding an axe.

I have never been so scared in my life. We ran very fast over the ridges with the axe-wielding man trailing us for about a hundred yards. He couldn’t gain on us. My cousin and I stopped once we realized the man was not chasing us anymore. Our hearts were pounding so fast as we nervously laughed saying that was a close call. When we arrived home, we never told my Sister and Brother-in-law of the scary incident because we knew we had no business wandering that far away from home into a stranger’s fields.

The Last Mango

I was 11 years old at Dzoole School in Chief Chanje area about 7 miles from Mgubudu stores on the Chipata-Lundazi Road in the Eastern province of Zambia. That’s where my father was teaching at the time.

It was at the very tail end of the mango season sometime at the end of January. The Mangoes were getting fewer and fewer. One sunny afternoon, I was hunting birds with a legina (sling shot), when I suddenly saw this bright red-yellow Mango right on top of a big tall Mango tree. I didn’t even think. I just raced to go and climb the tree because I had to have that delicious Mango. I had not eaten one in more than a week.

It was at the very tail end of the mango season sometime at the end of January. The Mangoes were getting fewer and fewer. One sunny afternoon, I was hunting birds with a legina (sling shot), when I suddenly saw this bright red-yellow Mango right on top of a big tall Mango tree. I didn’t even think. I just raced to go and climb the tree because I had to have that delicious Mango. I had not eaten one in more than a week.

As soon as I walked into the think underbrush, it was very dark as I crunched the dry mango leaves on the ground with my feet. As I hastily climbed the tree, I kept my eyes up to where the mango fruit was with rays of bright lights breaking through the thick green leaves. Half way up the dark tree, I heard the loud buzzing around my head. I knew right away what they were. Instead of climbing down, I just let go and fell the rest of the way; thud!! to the ground and got up and ran.

With the large big black buzzing of all the ferocious mabvu, masanganavo or wasps, I was lucky because I was bitten only once right above my left eye brow. I thanked my quick reflexes and instincts. Talking about mabvu or masanganavo or wasps, if you were a boy, being stung while hunting birds and wondering in the woods and bushes was a rite of passage.

But I had a huge problem. How was I going to hide this from my mother? My eye was already swelling and soon it would be swollen shut. Some thoughts went through my mind. I could go home late after dark and then slip into bed, or I could run away for a few days. But where would a kid with a swollen eye go? I didn’t know anyone I could ran away from home to. I decided to go home but I would try to hide this calamity from my mother. I must have walked home sheepishly because right away as soon as my mother saw me she asked:

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” I replied as I kept the left side of my body away from her.

The next thing I heard from her is:

“You have been stung by wasps, what were you doing?”

“I was trying to get a mango,” I confessed since I figured she caught me. There was not sense trying to lie.

“You act as though I do not feed you,” my mother said sarcastically. “ You just had a big lunch of delicious nshima. Why were you looking for a stupid mango for? How hungry can you be? You deserve to be stung. Now, I hope you have learnt your lesson.”

My younger siblings came and gawked at my left eye which was swollen shut by this time. My mother didn’t know I was so relieved it was over. I had expected worse. Fortunately my father was not even home. The following day the swelling was gone and I was back in the bush again.

Fond Memories

Among numerous fond memories of Mangoes is the season in January 1976. I was a senior at University when I lived in the village for one month with my parents. As soon as I arrived in the village, I immediately joined my parents in the growing season everyday routine of hoeing and tilling of the land to grow maize, peanuts, sweet potatoes and a dozen other foods. I woke up at 5:30 am, washed my face, and carried the hoe on my shoulder walking through the bush path to our family field. Mango trees were all over the village and the field. But there was this one Mango tree which was about a hundred yards along the path. Every morning, I detoured to the Mango tree in the bush and would pick up 3 or 4 large delicious Mango fruits that had ripened overnight. I would eat them and continued on the path to the field.

My father would already be in the field. I would join him. My mother and some of the younger siblings came later with my mother. My mother would be carrying late breakfast and lunch which we would eat in the mphungu grass shelter. One of the siblings would also be carrying a basket of fresh mangoes to the field.

My father would already be in the field. I would join him. My mother and some of the younger siblings came later with my mother. My mother would be carrying late breakfast and lunch which we would eat in the mphungu grass shelter. One of the siblings would also be carrying a basket of fresh mangoes to the field.

We would eat porridge with peanut powder and sometimes drink the sweet mthibi traditional brew which is cooked from finger millet. Once we finished hoeing, at about 4:00 pm we would return to the village where I would take a bath. After wards, I would eat supper of nshima sometimes with fish or beans, and other vegetables with my parents. The following morning, I would wake up following the same routine. I would detour to the same Mango tree to eat a number of them that had become ripe overnight. I remember telling myself that the Mango tree was my breakfast table. Indeed, growing up and going to school at Boyole, I remember we students naming one of the Mango trees by the edge of the school “JemuJemu” which translates at “bitebite”. When school would dismiss, some of us would climb up the tree and eat one Mango before we headed home. We would be playing all the time.

Looking Back

Every community and villages in rural areas love and know all their children. Both the scary incidents were meant to protect the young crop and also unripe green mangoes as children are generally careless. Mr. Ngamira probably had heard us coming to his field through the path long before we had arrived. He had probably climbed and hid in the tree. When he thought we were near enough he had thrown the two mangoes one after another knowing neither one of the Mangoes would hit or hurt us children. We experienced something scary and exciting. We ran and told other children back in the village not to wander into Ngamira field as there are mysterious creatures that throw mangoes at you if you go there looking to eat Mangoes. Adults including my Grandmother probably knew what had happened all along.

The axe-wielding man also merely pretended to want to axe us. At one time during the brief chase, he was close enough to really use his axe to hurt us. But he didn’t mean to and knew that scaring us would ensure that we would tell the story to other young boys. I am sure the man for the next few years had no children trampling and destroying his crop while looking for Mangoes. He probably even knew my brother-in-law and shared the funny story with other older men.

Conclusion

Contemplating the natural goodness of the Mango fruit and how people in my rural community enjoy the fruit so much, my thoughts focus on the possibility that the fruit may have been created from the goodness of God. In many instances just as I cannot explain some of the wonders of life and the universe, my thought never wander too far from the power and goodness of God. How else can I explain the natural magnificence and beauty of the fruit that I and so many people love so much?