by

Mwizenge S. Tembo, Ph. D

Professor of Sociology

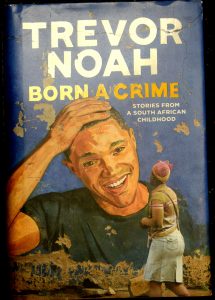

Trevor Noah, Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood, New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2016, 288 pp. K272.00 ($28.00), Hardcover, K155.00 ($16.00) Paperback.

Introduction

The diabolical South African racist apartheid policy felt its first death blow when the late great legendary Nelson Mandela was released on February 11 1990 after being in prison for 27 years. The crime for which Mandela was jailed was fighting against apartheid in the early 1960s. Africans and the world hammered the last nail into the racist apartheid coffin on April 27 1994. This is when all the estimated 40 million South Africans of all races; blacks, whites, coloreds, Asians and others held their first democratic elections under a brand new constitution.

Legacy of Racism

When Europeans introduced racism or what was known as color bar in British colonial Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, that was bad enough. What was worse is when Europeans introduced racism on the entire African continent with whites always portraying themselves as superior and blacks as inferior. Black South Africans were the worst victims of racism as apartheid was uniquely formally codified into elaborate state laws of South Africa from 1948 to 1990. Although European colonialism formally ended in the 1960s when most African countries gained political independence, Africans and the world are still dealing with some of the serious legacies of the ugly tragedy that is racism. What were the experiences of black South Africans under the worst excesses of the diabolical apartheid policy? How did apartheid negatively impact other groups such as coloreds and whites as collateral damage?

Trevor Noah is a high profile South African comedian who has reached the pinnacle of his unlikely career as host of the highly acclaimed The Daily Show television program in the United States. He has written a book about his experiences growing up under the dark shadow of apartheid in South Africa. The book can be best characterized as the great grand children of Nelson Mandela and South Africa vividly narrating the tragic and damaging story that was apartheid in South Africa.

Noah was born in 1984 and was only 10 years old when South Africa held its first democratic elections. There are no doubt thousands of books and other historical accounts that have recorded and will continue to unveil the evils of apartheid. But Trevor Noah’s story has a very compelling and useful uniqueness that most readers may miss. Some readers will read the book and conclude: “….apartheid was bad, Trevor Noah survived. He is now rich and famous. Apartheid and racism are in the past….” This is hardly the whole story. Trevor Noah, Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood, has a bitter sweetness to the book.

Bitterness

The bitterness to the book is that it vividly describes the pain and suffering that Africans in South Africa and elsewhere have endured and continue to suffer under various schemes of European racism particularly under apartheid in South Africa. The extreme poverty, high unemployment, the crime infested crowded shacks but culturally vibrant townships, racial segregation, poor schools, residential segregation, extreme hunger and life of squalor in the remote and rural dusty squalid African bantu stands under apartheid.

Describing some of the deeply divisive and cruel aspects of racism, Noah says:

“If a black guy chooses to button up his blackness to live among white people and play lots of golf, white people will say, “Fine. I like Brian. He’s safe.” But try being a black person who immerses himself in white culture while still living in the black community. Try being a white person who adopts the trappings of black culture while still living in the white community. You will face more hate and ridicule and ostracism than you can begin to fathom”.(2016: p. 118)

Some of the ugly aspects of racism Noah describes as a child are reminiscent of Malcolm X’s experiences growing up in his black American family in which his parents treated more favorably his siblings who had lighter skin.

“There were so many perks to being “white” in a black family, I can’t even front. I was having a great time. My own family basically did what the American justice system does: I was given more lenient treatment that the black kids. Misbehavior that my cousins would have been punished for, I was given a warning and let off.”(Noah: 2016, p. 52)

And then there was the heart wrenching violence of necklacing among Africans, especially between the Zulu and Xhosa, from various so-called rival tribes in the townships during the dying days of apartheid as they vied for power and influence in the townships. One wonders just how a kid from a mixed racial background that is Trevor Noah survived. His mixed race of being colored, born of a black mother and white father, was both a blessing and a curse.

The silent victimization of whites under apartheid is often underplayed with the assumption that after all, all whites loved apartheid because they were benefiting. But many whites suffered physically but also suffered the invisible pain of the soul for they could not live as complete human beings with total freedom. Trevor Noah’s white dad could never fully openly enjoy life with his son and his son’s black mother. Because under apartheid they were all a living and breathing crime scene every single day of their lives.

The other form of bitterness of the book is more hidden. This is not Trevor Noah’s fault for he is only narrating what I have no doubt are accurate experiences. It is what I would characterize as the sweeping power of Europeanization, Westernization, therefore urbanization. Noah’s father and mother are living in vestiges of extremely rural cruel oppressive patriarchal customs which his mother feels at liberty to mock when she visits her African husband rural village. Some of these patriarchal customs tragically result into gender based violence. These violent aspects of the culture should be totally eliminated. But one has to be cautious as there is a danger in eliminating all of the strong African traditional customs because many of them are beneficial even for couples who are married and both have Ph. Ds. Urban people nearly everywhere, more especially in African and among their European counterparts, never fully understand and fully appreciate some of the positive rural customs among the so-called rural tribes in Africa.

Another bitterness happened when Noah and his mother eat raw green caterpillars as food because of poverty. The caterpillars explode in Noah’s mouth to his disgust. I laughed. The green caterpillars are vinkhubala or matondo in rural Zambia. When they are properly cooked and sun dried and roasted they are very delicious. They are sold in many township markets in Zambian towns and rural roads. Of course you can never find them in the modern city supermarket.

The Sweetness

The sweetness of the book is that there is triumph of good over evil. In spite all the obstacles he and his African mother faced, Trevor Noah emerged strong from under the abyss of apartheid. Some of the heroic action Noah’s mother expose some of the contradictions that exist in child upbringing among some Africans and African-Americans up to this day. This is the notion of why should parents teach and expose their black child to “white culture” if the child will never be part of the white culture? The white culture often is in form going to museums, going to libraries, reading, speaking so-called white middle class English or bazungu English, visiting parks, just exposing your child to different cultural experiences outside the African culture family comfort zone. Noah’s mother exposed her young son to as much of the outside non-black world as she could. It might have helped her son succeed and have more choices and opportunities later in his adult life.

Discussing how his mother exposed and educated him so much about life during apartheid, Noah says: “People thought my mom was crazy. Ice rinks and drive-ins and suburbs, these things were izinto zabelungu – the things of white people. So many black people had internalized the logic of apartheid and made it their own. Why teach a black child white things? Neighbors and relatives used to pester my mom. “Why do this? Why show him the world when he’s never going to leave the ghetto?” ………I was nearly six when Mandela was released, ten before democracy finally came, yet she was preparing me to live a life of freedom long before we knew freedom would exist.” (Noah: 2016, p. 74)

The sweetness of the book shows the incredible resilience of African people. We are not only the origin of all 7 billion people in the world going back perhaps a hundred thousand years, but European slavery, colonialism, racism and apartheid are only a small bump in our long history. If you are a Zambian or an African, you ought to be proud of Trevor Noah’s story of resilience. If you are reading this story as a member of humanity, you ought to be proud that human beings can exhibit so much strength in the face of insurmountable difficulties. The message from the book is that you can also overcome anything.