by

Mwizenge S. Tembo, Ph. D.

Emeritus Professor of Sociology

Author of “Sayings of my Mother”.

Introduction

After graduating from University of Zambia in 1976 with a double major in Sociology and Psychology, I was a Staff Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Institute of African Studies of the University Zambia. The following year, I was very excited to fly to the State of Michigan to do my Master’s Degree in Sociology at Michigan State University in the United States of America in September 1977. After spending a long successful three years away from my beloved country of Zambia, I was ready to return home in January 1980.

Although I had spent the best of times while in the United States, there was nothing better than sweet home. I had a small contingent of Zambian and African student friends with whom I had a good time. But for all those years, I had been periodically home sick as letters from relatives and friends in Zambia took six weeks. International phone calls were expensive, cumbersome, rare and largely unknown. The inventions of emails and cell phones were still 28 years away.

One of the most important things I greatly missed when I was away from home for those three years was speaking my Tumbuka mother tongue language and the Lusaka Nyanja. As I boarded the plane in Detroit in the United States to return to Zambia, I was very happy and nervous. What would it feel like to speak Tumbuka again after speaking only English for those long 3 years? Will I have forgotten how to speak Tumbuka my mother tongue? How exciting was it going to be when I was back in the streets of Lusaka for the first time listening and talking to my fellow Zambians in Lusaka Nyanja? It was going to take me over 24 hours to fly to Lusaka. First, I had a layover of 12 hours at London Heathrow Airport in the United Kingdom before flying to Lusaka later that evening.

I boarded the beautiful giant Zambia Airways DC 10 jet with Zambian flag colors painted on the outside. I sat down in my seat and was fastening my seat belt when the sweetest thing happened. One young Zambian man steward was near the front of the plane while gesturing and communicating with another young woman stewardess who was toward the back.

“Iwe, kabili uleteko pilo imozi when you are coming back,” (Bring one pillow when you are coming back this way) the woman said in a typical Lusaka City Zambian language.

“Ningalete bwanji pilo kabili I have to bring drinks pa tray for abo ma passengers on the way apo pakati.” (How can I bring the pillow when I am carrying drinks on the tray for those passengers in the middle?) the man responded pointing to the passengers.

At that moment I was so happy, thrilled, and overjoyed. I was tempted to rise up and hug the stewards while jumping up and down and dancing repeatedly shouting: “I am back home! I am back home!” But I had to restrain myself. I was afraid I would be arrested as a deranged passenger and the Heathrow Airport police were going to escort me out of the plane and detain me as a mad man.

Forty-four years later I still get goosebumps when I remember that moment of great joy. This is the power and significance of language. Language evokes some of our deepest memories of moments of social intimacy in the society and the group to which we belong. When I arrived at Lusaka International Airport early the following morning, my uncle the late Mr. J. J Mayovu met me at the airport. He welcomed me as we hugged and spoke our deepest Tumbuka, my mother tongue. I spoke Tumbuka smoothly. We laughed as I was so happy to be back home on Zambian soil with my family and my beloved fellow citizens of Zambia.

Objectives

The objective of this article is to discuss the challenges or problems of publishing in Zambian native or indigenous languages. Before I discuss the significance of Zambian indigenous languages, I should discuss why perspectives on the subject of publishing in indigenous languages are uniquely important at this time in 2024. I am among the few Zambians today who are 69 years and older and have had experiences sixty years ago from the 1950s about indigenous Zambian languages that may benefit the 19 million Zambians today.

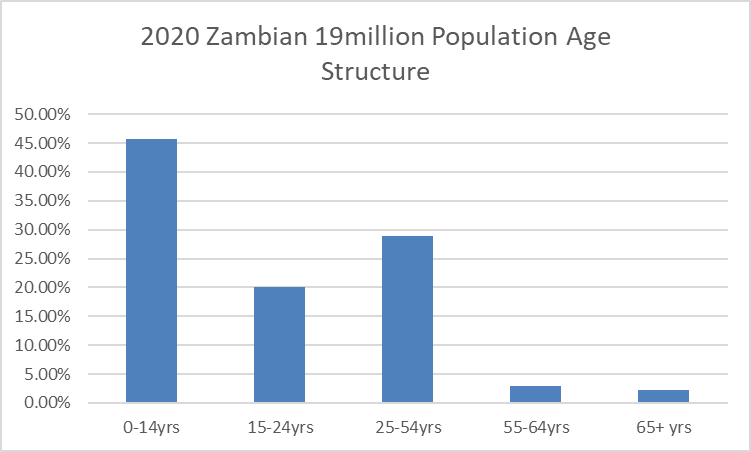

The population of Zambia in 2020 was estimated to be 19 million. The proportion of the population in the country that was under 14 years old was 45.74%, those between 15 and 24 years old were 20.03%, those between 25 to 54 years old were 28.96% and but those between 55 and 64 years old were only 3.01% and those above 65 years old were even smaller proportion of 2.27% or 431,300 of the population of 19 million. These few surviving about 5% of the population are the few people who were born before 1955. These are the few remaining people who are supposed to be both custodians and transmitters of the 72 Zambian indigenous or native languages.

The age statistics that are the most important for the crucial possible important role of older speakers of indigenous Zambian languages, like this author, are that Zambians that are younger than 30 years old may be about 70% of the population which is about 13.6 million young girls, boys, women and men. Therefore, there are fewer elders today in Zambia to teach younger people about our history, customs, native languages, and our traditional culture, perhaps due to the high death rate in the 1980s of older Zambians who are now over 55 years old because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. A large number of Zambians who would be about my age of older than 69 died in the late 1980s because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Urbanization also takes its toll in weakening the influence of indigenous languages in Zambia as the 45.15% of the urban population is rising. This means increasing numbers of Zambians leaving rural areas lose their connection to rural areas where the source, strength and origin of our traditions are the strongest especially including spoken indigenous languages.

Number of Indigenous Languages in Zambia

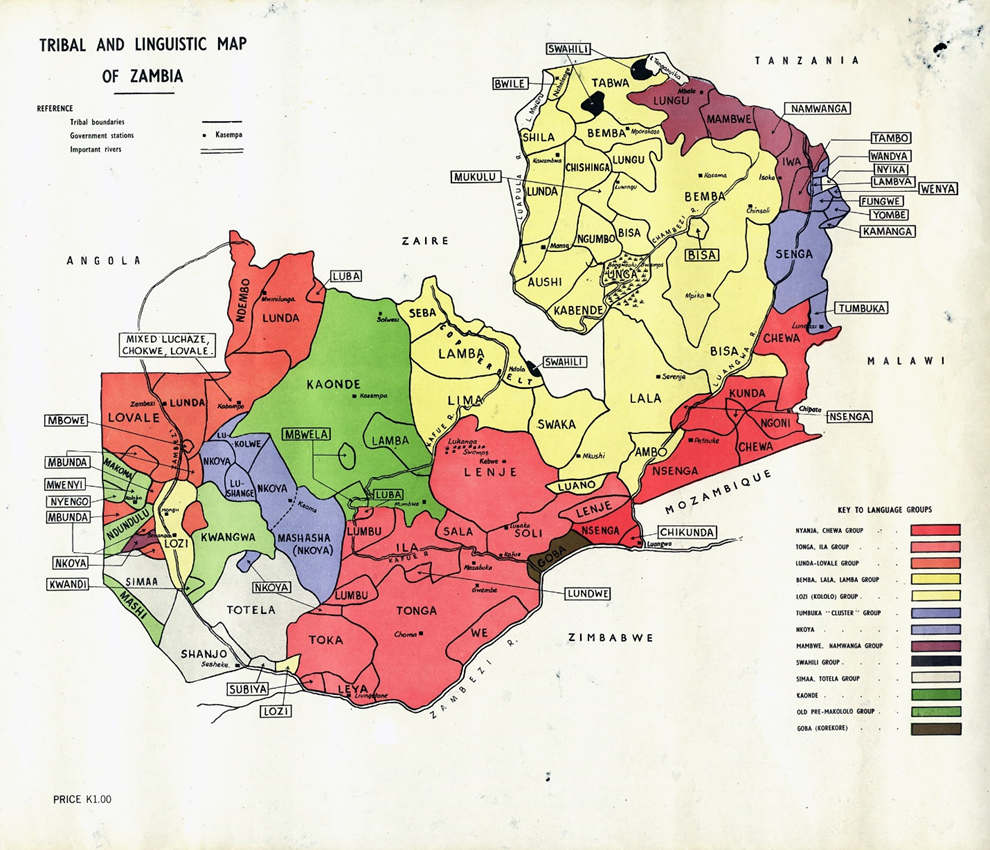

A discussion of Zambian languages would be incomplete without first determining how many indigenous languages exist in Zambia. According to the Wikipedia, there are 72 indigenous languages in Zambia with English being the official language. Some experts argue that these 72 are not all languages as some are dialects.

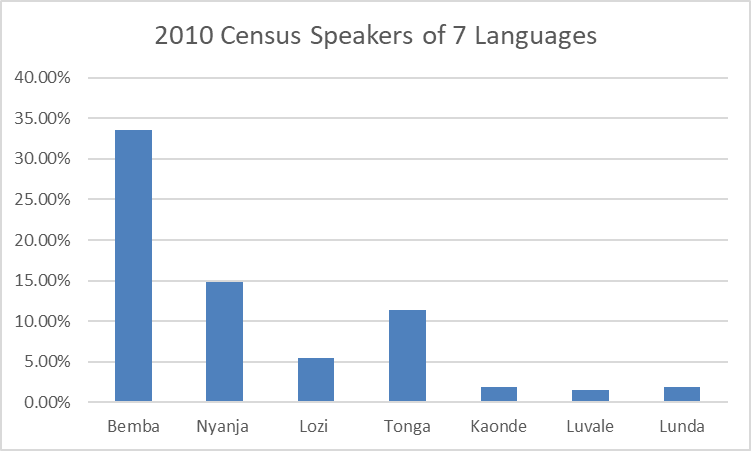

There are seven native or indigenous languages that are officially recognized by the Zambian government. According to Wikipedia, these seven languages also represent major regions of the country. Bemba is spoken in the Northern Province, Luapula, Muchinga and the Copperbelt. Nyanja is spoken in Lusaka and the Eastern Province, Lozi is spoken in the Western Province, Tonga and Lozi are spoken in the Southern Province, and Kaonde, Luvale and Lunda are spoken in the Northwestern Province.

How many people of the 19 million Zambians speak these indigenous native languages. According to the 2000 Census Bemba is spoken by 35% of the population, Nyanja 37%, Tonga 25%, and Lozi 18%. According to Gordon, data from the same 2000 Census shows some of the languages having very small numbers of the Zambian population speaking these languages as first, dominant or primary language in their lives; Bemba 30.1%, Nyanja 10,7%, Tonga 10.6%, Lozi 5.7%, Kaonde 2.0%, English 1.7%, Lenje 1.4%, Namwanga 1.3%, Senga 0.6% and Lamba 1.9%. What these numbers suggest is that the seven indigenous languages may represent certain regions and populations of the country. But do the people, most or some of them, speak only these languages in their everyday lives? These questions bring me to the problem of putting the cart in front of the horse or putting the cattle bulls in front of the cart or wagon. Both animals may never be able to pull the cart forward.

Putting Cart in Front of Horse

If you want a horse or 2 cattle bulls to pull a loaded cart or wagon, it makes sense to tie the animals in front of the cart. Then they will be able to pull and carry the loaded cart forward. But if you make the illogical mistake of putting the cart or wagon in front of the bulls or the horse, the cart will never be pulled forward. This is a cautionary tale on how to handle the issue of challenges and problems of publishing in Zambian indigenous or native languages for the speakers of the languages. Any new policy advocating change must be aware to avoid putting the cart in front of the horse.

Zambia has had a policy of communicating, broadcasting, publishing, and teaching in the seven official native languages since independence in 1964. The Ministry of Education officially approved the orthography of the 7 languages in 1977. There may be fewer Zambians today speaking and let alone reading and writing using the seven languages. If a new policy of publishing as rights to free expression is advocated, wouldn’t that be placing the cart before the horse since fewer Zambians may be reading and writing using these seven native languages? If, however, Zambians are speaking using some of these native languages in larger numbers, shouldn’t the new policy focus on the spoken language only? These are some of the ideas that will be discussed in this article. Next will be the description of the major objectives in discussing challenges and problems of publishing in Zambian languages.

Objectives

The article will next first explore how to help promote writing in languages that are not part of the 7 languages used in education and on national media. Second, discuss the assertion of the fact that the 7 languages used in education and national broadcasting were bestowed upon us Zambians by missionaries. Third, explore and show the value of linguistic diversity in national development. What can we gain as Zambians by having literature – folktales, poems, music, intangible cultural heritage expressed in all the languages in Zambia? Fourth, investigate what are the historical and current problems of producing literature and other art works in so-called minority languages? Fifth, examine what are some of the best practices around the world where artistic expression in all languages of a country is promoted?

Exploring how to help promote writing in languages that are not part of the 7 languages used in education and on national media should pose many hard questions rather than just provide easy policy answers. The answer to this question also answers the fourth objective of this article: investigating what are the historical and current problems of producing literature and other art works in so-called minority languages?

These hard or difficult questions are justified if your serious aim is to avoid placing the cart in front of the horse as proposed earlier in the article. Before we even discuss how to promote writing in languages that are not part of the 7 languages used in education and national media, do we have a booming and thriving existing writing, reading, and publishing in the 7 languages among the vast majority of the 19 million Zambians? If the answer is likely no, what would be the justification for the Ministry of Education, policy makers, and Right to Write advocates for supporting expanding writing in languages that are characterized as minority languages because very tiny numbers of the 19 million Zambians speak those languages? For example the author’s Tumbuka language has 2.5% primary speakers, Lenje 1.4%, Bisa 1.0%, Lungu 0.6%, and Lala 2.0% just to mention a few of the 72 languages and dialects.

Another very important factor that must be considered is the distinction between primary and other speakers of a native or indigenous Zambian language and those who might be readers and writers of the languages. Speaking is the easiest, least costly, and most direct way to learn and enjoy directly communicating and creating immediate emotional connection and unity between the speakers. Audio books may be more accessible to most Zambians rather than books. However, becoming a reader and writer in the language is more demanding and more difficult to achieve and enjoy. Reading requires investment in both formal schooling and machinery for printing when publishing in the Zambian languages. The financial capital required and other resources may be in short supply in a Third World country like Zambia.

Discussing the assertion of the fact that the 7 languages used in education and national broadcasting were bestowed upon us Zambians by missionaries may be a legitimate observation. But should we throw out those missionary and colonial decisions? If we did this as Zambians, that would be throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Let’s keep some of what the missionaries established.

I had bought a Tumbuka Bible at a Christian Bookstore that used to be located in Chamba Valley near Kaunda Square in Lusaka in the 1980s. I lost that bible and wanted to buy another one in 2022. The Christian store did not exist and I spent all day driving in Lusaka to many different places. I could not buy a Tumbuka Bible anywhere. Are any of the publications or books in the 7 official Zambian languages widely and easily available anywhere in Zambia? Occasionally I see that Maiden Publishing has some books in Zambian languages.

The only thing that might be true today is that the number of Zambians who speak exclusively just one of the 7 native languages chosen by missionaries may have shrunk. Multilingualism is much more common in Zambia than might have been 60 years ago in 1964 at Independence.

Dr. Sombo Muzata is a millennial who was born between 1981 and 1996. A brief conversation I had with her may illustrate some of the challenges or problems in publishing in Zambian languages. Dr. Muzata is Assistant professor or lecturer at James Madison University in the United States of America. Her father was Luvale. Her mother was Bemba and she was primarily raised in her mother’s Bemba family. Her native languages are Luvale and Bemba. She can speak Chewa/Nyanja. She can understand and can speak Tumbuka. She can understand other Zambian languages too, but can’t speak them fluently. Dr. Muzata may represent thousands if not millions of Zambians who are multilingual. How would publishing in Zambian languages be implemented when there is so much that has changed and is unknown?

Dr. Muzata concluded: “….our Zambian languages define us as a people. They are a core part of who we are. I look for any opportunity to speak my language and those that I know. I hope people are proud of their languages and can speak without shame.”

The new multilingual population of 19 million Zambians may have a different language population distribution, needs for spoken languages, reading, writing, and publishing. Their media participation given the internet may be different from the Zambians who spoke the 7 original languages established or chosen by the missionaries from the early 1900s to 1964.

When I was researching and writing my book: “Satisfying Zambian Hunger for Culture” in 2012, I faced a difficult challenge. I was writing Chapters on “The role and influence of traditional dances among Zambians” when I could not find any research material on “YouTube” and other social media, and the internet about the dozens of traditional dances in rural provinces of Zambia. Today in the social media in 2024 I thoroughly enjoy spending hours watching video clips of dozens of Zambian traditional dances which Zambians from rural areas upload.

The significance, exploration and showing the value of linguistic diversity which is embedded in cultural diversity in national development, is evident in contemporary culture of Zambia. What we gain as Zambians by having literature – folktales, poems, music, intangible cultural heritage expressed in all the languages in Zambia is self-evident especially in the diversity of the music and dance today in Zambia. Comedy and other shows on television that include different Zambian languages speakers including English. The internet, social media, the variety of dances at Kitchen parties and wedding receptions demonstrate the multicultural and multilingual nature of Zambian society.

Fifth, examining what are some of the best practices around the world where artistic expression in all languages of a country is promoted can benefit us Zambians only if we have definitely found what works and does not work for us. Professor Muna Ndulo once warned that adopting new foreign cultural practices from different countries is not like buying a new refrigerator. If you buy a new fridge, if you have the right voltage, you can plug it in anywhere in the world, the fridge will work perfectly. But this is not the case with culture. You cannot export democracy or a religion, for example, and simply introduce it to a country and have it work. This may be the challenge for Zambia in the attempt to encourage publishing and promoting native or indigenous languages including the 7 languages that are officially recognized used in education and the media. It will not be easy to simply mimic or copy what other countries have done.

Recommendations

1. The government, all political parties, and top experts in institutions of higher learning should conduct a massive survey covering the whole country. The survey will determine how many Zambians are speakers, readers, writers, radio and media viewers and listeners of particular specific Zambian languages. What proportion of the Zambian population are multilingual and in which Zambian languages? The 7 official Zambian languages should be included in the focus of the survey.

2. The results or findings of the massive survey should be used to implement policies that will promote the use of Zambian languages through internet social media, publishing of books, and audio books. The results should be used to conduct all annual writing competitions with awards in all schools in designated Zambian languages. The competitions should be in literature – folktales, poems, music, intangible cultural heritage expressed in all the languages in Zambia and especially Zambian traditional music.

3. The Zambian government should establish a major publishing and printing, and media communication center for printing, publishing, and producing all creative material in Zambian languages. The printing and publishing should be heavily subsidized by the government so that the published material, especially books will be cheap and affordable by all citizens of Zambia from the rural to urban areas.

Conclusion

The significance of our 72 mother tongues, dialects, native or indigenous languages is that they represent some of our deepest expressions and connections to our families, relatives, friends and country. The history of our primary languages goes back to perhaps thousands of years living and migrating on the vast African continent. All the Zambian 72 languages may have buried in them thousands of years of some of our Zambian/African history and deepest indigenous knowledge and influences on the world. For example, Dr. Chisanga Siame, using historical linguistics, philology, the etiology, phonology, and morphology of Zambian and African languages discovered that the Bemba term uku tunkumana about two thousand miles away South of Egypt may have descended from the name Tunka Men the name of the ancient kingdom of Sudan suggesting a connection between the Bemba of Zambia people and the ancient Egyptian civilization.

This article deliberately does not have definitive answers on policies for publishing in Zambian languages because answers are difficult to come by as the situation of languages has been very complex and changing since Zambia’s independence from British colonialism 60 years ago in 1964. The article asks more questions than provides answers because the article is meant to provoke thought, question some of the existing policies, and stimulate discussion. The future is unknown as our increasingly multilingual society of One Zambia One Nation is different from what it was 60 years ago at independence in 1964. This author is one of the very few Zambians who have lived through this long period and have lived through and witnessed the social change in language.

How do we as a nation effectively teach speaking, reading, and writing both English and our 72 native or indigenous languages, especially the official 7 languages of Bemba, Nyanja, Lozi, Tonga, Luvale, Lunda, and Kaonde? The Zambian Education system has tried several different policies but none have been found to be very effective, or at best have mixed results, in achieving good standards of speaking, reading, and writing the English official national language and the 7 official Zambian languages.

Sources

1. 2010-Census-of-Population-National-Analytical-Report.pdf

5. https://zamtransinternational.weebly.com/zambianlanguages.html

6. https://www.britannica.com/place/Zambia/People

7. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-zambia.html

9. https://www.indexmundi.com/zambia/age_structure.html

12. Zambia Language Policy: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=stcloud_ling#:~:text=Following%20the%20belief%20that%20%E2%80%9Cone,recognized%20in%20the%201991%20Constitution.

13. Mubanga Kashoki, “Rural and Urban Multilingualism in Zambia: Some Trends,” in International Journal of the Sociology of Language, March 1, 1982.

14. https://pen.org/zambian-pen-center-promoting-literature-indigenous-languages/

15. https://ila.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/rrq.180

a. Sylvia C. Kalindi, Catherine McBride, Lin Dan, “Early Literacy Among Zambian Second

b. Graders: The Role of Adult Mediation of Word Writing in Bemba”,First published: 08

c. March 2017

16. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0021934713480801

Chisanga Siame, “Katunkumene and Ancient Egypt in Africa”, Journal of Black

Studies, Volume 44, Issue 3, First published online March 20, 2013