Unedited Diary of a Young Teenager – Book One

August, 1969

I went home that day semi-discouraged and encouraged. I had very high hopes, expectations, dreams and imaginations about my school holidays.

On the other hand, I had planned with my best friend to go for a picnic during the holidays. We planned to buy fishing hooks, lines, and packets of pullets for bird air gun. We would go down the Rukuzye dam for fishing and swimming. Later in the day we would collect my air gun and his and go for hunting birds around the Rukuzye River, and return in the evening probably with large quantities of fish and stupid birds of the Rukuzye. Those were our plans.

But suddenly, like a flash, my best friend died one week before the holidays. Sorrow wounded my soul and I was deeply grieved. Tears once came to my eyes but my thoughts went back to the time when my younger brother died of rabies Tamanda Upper Boarding School. I had cried and my bed sheets had become wet with what had felt to be hot tears. The head teacher had called me to his house. I went there and wondered what he would say to me. I realized afterward that the whole point was to comfort me. I was given a cup of coffee and he spoke to me some comforting words. He told me that time for writing secondary school entrance examinations was nearing and I should forget all about it. At that point the tears had disappeared.

I felt pity for my dead friend once more when I thought of sleepless nights when we used to chat together about some adventure in boy life. I remember, one night my brother-in-law had to come and knocked on our bedroom door to advise us not to make noise and we kept on chattering in low tones. But now he was gone.

“I should forget all about it,” I said to myself.

But that atmosphere of sympathy hang on me for some time. I would have missed him a lot if I had decided to go home for my holidays. So my mind was diverted completely to another course. Therefore I chose to go to the City of Lusaka. On the school closing date, I went home and collected money for transport from my father. I came back happy in mind and awaiting for night to come which would give away the scent of the following day. Since the school was closed, I slept late that night with my friends.

The morning was cool, no signs of sun rise yet. I looked through the window and saw that it was cloudy all over. I went to wash my face and still no sun. So I knew that it would be a cool day. I was just packing after dressing when the engine of a fiat bus sounded in the school road. Probably it was a Msoro bus but news came that it was going to Lusaka. So early! Some boys were still asleep they had to be woken up. They dressed and shuffled their blankets quickly into their suitcases. We all rushed to the car park where the bus was standing still with no signs of hurry. I bought a half fare ticket and boarded the bus with my small hand suitcase specially taken for the journey.

Boys had already began sucking at their cigarettes immediately after taking their seats. The driver in every one’s eyes promised to be good particularly at fast driving. They whispered to say he was very young and fit.

Presently the bus was full and nobody was entering any more. In other words all the Lusaka route boys were in. He started the engine and pressed upon the accelerator resulting into the sound of G-y-i-me! G-y-i-me! Off we went.

We were all disgruntled during our journey judging from the atmosphere in the bus.

To begin with, the constant unnecessary stops he made were not comforting. He packed us like sardines. From the door, near his seat, in the seats, it was everywhere people. When it stopped one felt as if one was in an oven. Small children and babies were yelling. I was told that children don’t take in enough oxygen. One child was thought to be sick. It cried and gasped like a long distance runner.

At Nyimba, after a rest of about one hour, everybody was in to resume the journey and the driver was at the wheel too. Among the entering people, there came a man in dark brown jacket, dark trouser and white shirt.

“Ey! you two boys come here!” he exclaimed. “Stupid, come out! You fools!”

The two Chizongwe boys stopped talking and rose to go out.

“Why do you dare insult him!” the man continued. “You are very foolish boys. Quickly! Come out! You are going to remain, this is Nyimba if you don’t know. Come out! and collect your suitcases!”

We didn’t know what was happening. They went out into the darkness. We couldn’t see what was happening outside since bus lights were on. Four big boys from Chizongwe went out to help or probably to see what was happening. Everyone asked his neighbour what had happened. Nobody knew. At this point, the driver went out also. Shortly after 10 minutes they all matched in and settled down. We went on.

After 30 miles of travel from Nyimba, some boy was alighting and while he was looking for his suitcase which was underneath the others, the driver began.

“These boys are very talkative. I advised them earlier on not to talk too much. Without me they should have remained no doubt. That man was the Bus Inspector. He was outside the window and he heard them insulting me. I didn’t hear them but the inspector heard. The boys think because they have “forms” they can insult anybody anyhow? This is very bad. They were going to sleep there and the police would come to collect them to Chipata instead of Lusaka. You young men should take care.” From that moment the journey went on with utmost silence. People were all asleep. We arrived at Kamwala bus terminal in Lusaka on a Sunday morning at about six o’clock.

I got a lift to Olympia Park area with some other two boys. The taxi at last turned at 6 Machester Road and I went to find out whether people were up yet since it was so early on a Sunday morning. A face opened a curtain a little on a Sunday morning. A face opened a curtain a little and saw what was outside. He had obviously seen me. He opened the front door and said “Oh! at last you have come!”

Uncle Chambula got my suitcase. I paid the taxi driver and he drove off. He took me into the strange house. The first thing I saw was a living room, with nice sofas. A radio gram, a good carpet and some house decorations. He took me to the spare bedroom.

“Have you had sleep?” he asked.

I said “No.”

I had sat up all the night long. He told me to have a sleep first. Although I told him I had enough blankets. He gave me another one. It took me long to sleep. The engine was still rattling in my mind and ears. I looked through the window before sleeping, I saw a small girl of about 13 drawing some water from the garden tap. I didn’t know who she was. Probably Jennifer? Can’t she be Theresa? I would see later. I covered myself with the blanket and slept.

I woke up and found out that I had dreamed nothing. I got out of bed and sat up. He showed me the bathroom and the toilette. I body washed myself with warm water coming from a geyser. After washing my weariness disappeared and instead there came a feeling of being at home. I went into my bedroom and dressed myself into proper and clean clothes.

Immediately after dressing, I was taken to the breakfast table. On the way he drew behind my long sleeved shirt and asked whether I had any watch. I said “No.”

I had a cup of coffee, slices of bread with fried tomato in between them. I warmed up once more. I remembered that it was two days before when I had taken some warm food. At the table I was greeted by his wife, Aunt NyaDindi, who had a new baby boy born on 1st August. I told them of how I left parents at home and how I had managed to find my way to the house. They told me that they had gone to the bus station 5 times during the previous day hoping each time that I had arrived. After breakfast I was given a new watch and a new shirt. I was then told to prepare for a football match, while he went for prayers. For the first time in my life, my wrist had a watch of its own.

We had a delicious lunch. The nshima was in the center. Everybody served himself while charting about some important views of Lusaka.

At two I was beside him in the Vauxhall car. We set off Woodlands Stadium.

After two corners, we were in the Great East Road again, this time going towards the Chipata round about. Before we could reach it, we turned to drive in the New Castle Street up to where the street joins Churchhill Road. We parked at the petrol station for the car to drink two gallons of petrol. We proceeded to reach A Nkhazi’s house. I thought it was an office. But I discovered two weeks later that it was a house. I said how small it was! He went out and I was left alone in the car. I leaned on the door with the side glass winded in. I felt very proud for the first time. The young woman came and she sat in the back seat and she alighted somewhere near Katungu bar,

We were late for the curtain raisers. People were cheering aloud. What a vast number of people were there! I thought to myself. Before leaving the car we made sure everything was locked and that the car was packed in a place where it would be easy to get away after the match. In a new shirt, watch, and a good trousers I thought I looked a real boy.

That was my first time to see the famous zoom soccer star in full swing and prooved the constant praises in newspapers and many a mouth of people.

At six p.m we were back at the house, but the routes we travelled had completely confused me. So I remembered nothing otherwise very little.

Two days later I decided to go alone into the city to have a glance at it. I went during the late hours of the afternoon at about three o’clock. I went through the main roads without taking any short cuts in case they led me to unknown places there after get lost. I once more went through Manchester road, Chepstow road then the Great East Road, and up the New Castle street to where we had previously driven through by car. I once more arrived at the petrol station where the car had drank two gallons of petrol. I walked with care and kept each sign of the way back to the house. I turned right of the Church hill road towards the Cairo Road. I went over the high ridge with the train dashing underneath. I entered the Cairo road with anxiety. I had heard many stories of its beautiful flamboyance and its fame in many accidents due to the fact that it is always busy during working hours. I feared to cross these busy roads before looking at how owners of the city crossed and I would follow their example. I had quite a different imagination of the famous Cairo Road before. The two pictures didn’t match at all. During this time I managed to see how the robots function to help the flow of traffic. I bought an exercise book and a pen which I would use when writing an essay which the teacher had told us to write. I would write about the car which was at close hand. He had told us to write about any machine which has an internal combustion. I saw some good nice novels. But I had very little money. I reached home very late because I had taken long roads instead of taking short cuts.

After supper, I asked Uncle Chambula about how the robots operated.

“That is what we refer to as a highway code. You have got to follow the rules and directions otherwise you can be in a serious accident.” he said.

He explained everything for example, he said the pedestrian crossing is there to help those on foot to cross the road with less difficulties. He also said that, the one way road is there to prevent accidents. Afterwards I moved with less fear of getting lost since I had known the center stores of Lusaka and I had also known the main signs of the way if I happened to get lost.

Jennifer was a 13 year old young girl. She was relatively very short and skinny. She was one of the people who kept their hair carefully and done at times. She was very clever and talkative. I liked her for the qualities which fitted almost exactly with mine. We called her Jenny.

Thereza was 16, short, plump, girl with very small hair which couldn’t by any means get done but she used to comb it beautifully. She was less talkative and got all work done immediately after being told by the mother. Jennifer liked mini skirts but Thereza didn’t like them. We called her Treza.

Judy was a six year old eldest daughter of the family. She was skinny and clever too. One day, talking to me, she said,

“Kamthibi, come here. I want to tell you something in the bedroom.”

I said, “Oh! you can tell me just here,” and I put my ear close to her mouth. She said whispering; “Mr. and Mrs. Martin were kissing each other on their door step this morning,” and I laughed. How did she know that that was a secret? Mrs. Martin was a housewife. Mr. Martin was working in the city. They were both Africans.

Tyson was the eldest son of the family two years old and known as Ty or “Mdala”. At this age he was unable to eat nshima and as a result he ate farex porridge only. The second son was 1 month old known as Thomson.

Ledu Himba was a relatively tall man. A good houseboy. He was 20 but unmarried. I read one letter from his girl friend in broken English. She was telling him to stop visiting her since he wanted her to visit him instead. He was very funny. He drunk a lot too. He had written to Theresa that he wanted her.

Sophia was the new arrival in the family. She was about 17. She was taking care of the new born baby while Aunt NyaDindi the mother was at school teaching. Theresa had gone to her friend Dorothy. At Dorothy’s house there was John who told Theresa that he (John) was coming to see Sophia, the new house girl, because Ledu Himba was very sleepy. Ledu Himba was mad with rage when he heard this. Blinded with furry he went to ask John about this. John denied it and Theresa admitted that she was just joking.

With in a few days Jennifer was a partner in playing. We were in very close contact.

Judy was learning at Olympia Park school and she was very proud of it. She had influenced all the young ones, for example class music. There was one song which she had taught me:

One little finger,

One little finger,

Tap! Tap! Tap!

I asked Jennifer to show me her class exercise books. She showed me one. I asked her to show me some more but she refused. I rushed to her bed room. But she ran after me in pursuit. I didn’t know where the case was. She ran and took the book case from the ward robe and I was unable to get it. She was doing well in class.

Uncle Chambula was very funny at times. He didn’t take any beer at all. After returning from work he would complain of hunger and that hunger had produced babies in his stomach. His wife would hurry up in cooking nshima. On his arrival from work his son would say “Hullow, Mwana” in a childish manner. Closing his car his father would say; “Hullow, Mwana!”

Ledu Himba complained that he had no money. He asked Aunt NyaDindi to lend him 5 ngwee for a candle. The housewife gave her money. On his way to the grocery he was tempted to go for gambling so that he would gain some more money. As a result he slept in darkness because he had lost five ngwee during gambling. But one day he had won a pair of trousers in gambling by luck.

All these people played their part in amusement during my stay. After the month, we went to shop with Jennifer. We first went to Ankhazi’s house to hand some vegetables. We arrived at Mwaiseni store at about 9 o’clock. Jennifer was down stairs and I went up stairs to the clothes department. I hesitated whether to use the conveyor belt or not. But I had never tried it before. So I went round up the steps to up stairs. Presently, Jennifer came to give me some advice on which shirt to get. She told me that somebody wanted to see me. I asked who it was. She said she didn’t know them. We continued shopping. Then we asked the sales lady where we could find hair pins. She caught me by the shoulders. We both bent just to look between the two walls, with the moving conveyor belt directly in front of us. What a nice perfume she had. And she whispered while making some signs with her hand.

“A mahair pins mwana.”

We went down stairs and got the hair pins. I asked Jennifer to show me the people who wanted to see me. This was after buying my new shirt, shorts, socks and an underpants which amounted to Six Kwacha. She directed me to the man on the counter. He just laughed and spoke something in Bemba. He told us to go. Later on Jennifer told me that the men thought Jennifer had come with an older sister whom they could coax for a date. I was taken aback.

In the afternoon, I decided to write a letter to the Zambia Mail column of free for all. When writing I remembered the coming day. I wrote this:

OVER CROWDING BUSES

It has been discovered that when schools close parents seem to go on holiday too. The same thing happens during the opening of schools. Therefore I think it is advisable that parents should try to fix their time for going somewhere depending on the period of closure and opening of schools. This I think is necessary just to give chance to school boys and girls to rush quickly home to start spending their limited holidays. Otherwise if this goes on any longer, it will result into risking one’s life to get home quickly. Since if you stay at a station for a longer period, it may result into different things all together. For instance, thieves may rob you, money may finish and no food as a result.

I know that there are some parents who go somewhere at that time for some very important duties. The parents I mean are those, for example, who go to look for work, to visit their son in the city. Such parents I think can wait a bit longer to let the school transport periods go over and then they can start their journeys later.

Anyway, this is just a suggestion to parents otherwise their children will suffer the consequences of life.

I ended.

I didn’t post this letter. And yet it was nearer there. But I just felt very lazy to post letters. I thought to myself, but some parent may say everybody uses his own money, so why should he stop going on a journey? That is true yes but it should depend upon some one’s business. Anyway, after all I wasn’t going to post it.

On a Sunday afternoon I went for pictures at Calton Cinema. I had known short cuts by now. I took 30 ngwee for the entry fee. I arrived at the door rather late because they were already through with the introductory part. Afterall it wasn’t important. If somebody asked how the film was, I wouldn’t speak of the first small introductory part. I bought the 15 ngwee ticket and went in. The room was quite carrying many people. It was as dark as a moonless night except for the side exit lights. The film was a nice attractive one. About the beach boys at the beach with their girls at the club. The film ended very late.

When the day of departure came, Ledu escorted me to the station on Friday morning. The Chipata bus line was very long. I was discouraged. We sat there all day with my school mate George. After missing all the buses Uncle Chambula came at 7 o`clock to collect me to the house with his car. I was back the following morning in his car. After having no chance of buying a ticket that day, I decided to sleep at the station with some school mates. It became so cold at night that I couldn’t feel that I was covering myself with a blanket.

The following day was a critical one. There were many people on the Chipata line and as a result no proper line could be made. People were just pushing each other. Police came to help. By chance Evance, a school mate bought tickets for us. We hastily boarded the bus.

It was a Sunday hot afternoon. All the Lorries seemed to have died. Except for an occasional hooter of the train and the cars passing by seemed to be moving silently. The round-abouts and the Cairo Road seemed to be feeling lonely. The people in the shops’ corridors were not moving briskly like during any other days of the week. The loaded bus moved like a hungry centipede. The city wasn’t as lively as usual. All these left a departing impression with the city life.

The people in the bus weren’t active at talking. They all seemed to be murmuring.

After the Luangwa Bridge, I already started sleeping after that sleepless night and toiling in the sun. I was glad because the journey was mostly going to be done in darkness because I was so dirty.

Next to us was Joyce the girl we had recently known in the bus. She was attractive. We giggled with George speaking and discussing about her. Shortly afterwards, George gathered courage and went to sit beside her. They lowered their heads under the seat in front of them as if tying their shoe laces. They didn’t seem to be speaking. When the bus inner lights were on, people were surprised to see the change which had occurred during the darkness. From there, I couldn’t open my eyes until our arrival in Chipata. I was surprised to see the big welfare hall and the bus station. I was relieved on the other hand to be back home safely. My lips had been cracked while at Kamwala and now I didn’t feel at ease at all.

Joyce disappeared with an escort to the houses which were formerly for Europeans.

November, 1969.

Everybody in Form I, III, and IV became more happy as the water shortage crisis became more acute at Chizongwe Secondary School. Because that meant the scent of an elongated school holiday. This was late November 1969. We couldn’t read, everything in school was disturbed because of the absence of one thing “water.” Already two boys were in the hospital because of diarrhea and many more automatically would go. Due to that trouble, part of the school had to close earlier while Forms II and V stayed to write their final examinations which would decide and determine their unknown future.

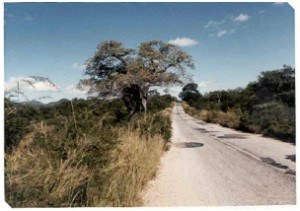

With the necessities of a newly established Chipata Dzithandizeni Nutrition Group depot, I went home with Mr. Leverkusen, my math Dutch teacher, the following day on a Saturday cloudy morning. Miss Spencer my Canadian English mistress had to accompany us. We arrived at my home after about 25 minutes of driving along the Lundazi road. This was at Kaulembe School where my sister and brother-in-law were both teachers.

We entered my sister and brother-in-law’s house and led them to the seating room which was rather too small. I gave Mr. Leverkussen and Miss Spencer seats. Mr. Mthetwa private nutrition salesman at Mr. Leverkussen’s house was given a seat too. My sister came in with minimum surprise because she had been told before of our coming.

Mr. Nkhata broke in with an automatic smile on his face. He greeted them and introduced them to him and vice versa. They started talking about nutrition depot and how it operates. Shortly, coffee was served with slices of bread. They stayed for an hour talking, they would go in and out of the nutrition topic. We would joke and laugh. Then Miss Spencer asked; “I wonder how this book for Canadian students is found in Zambia?” Mr. Nkhata said: “Well, it is one of the Canadian sisters who gave it to my wife when she was schooling.” Presently they both departed leaving a very warm farewell.

At the school where my brother-in-law taught, the school boys and girls were going by lorry to Tamanda Upper School for football matches. I refused to go with them and instead I went to fix or hang some posters about nutrition along the roads.

The school day for ballroom dance came and I was filled with uttermost excitement. But on the other hand I didn’t know how to dance it. I would learn and that word gave me a lot of encouragement so to speak. I brushed myself and put on nice clothes. When we entered, the radio gram was already there and everything available; ladies of any age but not more than 20 years and less than 8. Gentlemen were many, but the rest of the school teachers had not yet arrived. Nevertheless, we commenced.

We began with “Torture” by the Everly Brothers. Everybody took his partner but I couldn’t because I didn’t know how to dance it. After watching 4 records being danced to, I fell too for one lady and I tried. But I had many disadvantages; we couldn’t take an immediate corner and the quality of the dance itself wasn’t so good. Constant misses of steps were very disturbing. I had to admit before each girl that I didn’t know how to dance it. After many records I warmed up. One thing was no lady tried to resist if I tried to pick her up for a dance. I noticed many ladies taken aback if I went for them for four consecutive times. But one thing I found hard was I always failed to dance with a lady who didn’t look good before my two eyes.

There was a relation between us now. Every girl with whom I had danced previously used to either smile, look away or stoop with shyness.

When I thought back, the dance was so enjoyable. I had never dreamed of holding a girl by the waist and her breasts warmly touching my chest occasionally. But there was one thing which I had always thought of but why don’t the forces of nature react? I proved it this time. Nothing happened really and my curiosity was overcome. The next time, I would try to make it even more enjoyable I concluded.

There were a number of records which reminded me of dancing time. For example, “Listen to the ocean”. The others like ones sung by Virginia Lee remind me of the moment I was waking up in the morning because they were usually put on the radio gram during that time.

Hunting with a bird air gun was my main hobby for pleasure. My hunts left a good effect upon my sister and brother-in-law especially because I brought with me about 12 birds each time and this way I would save them the trouble of looking for nshima’s partner. This also revealed my aiming talent with my air gun. The school boys and girls knew this because the children would sit there with a plateful of birds while uprooting their feathers. I was proud of myself for being so good at long range shooting. This made me feel like a knife which is sharp on both sides both academically and at home.

I had never seen a girl as shy as Sophia before. After dancing ballroom with her, I never had a chance to look in her face even at a distance of 40 yards. If we happened to be at a place with an unavoidable closeness, she would always find a way of hiding herself. I had never made her talk except during ball-dance. Apart from that nowhere else. She dodged in a reasonable manner. I don’t know whether my only eyes would kill her. But she wasn’t as shy with boys of her school.

Days flew by at a tremendous speed like that of Apollo 11. With usual happiness days still passed. The closing night came, we had been sleeping at 2 a.m for the past 2 days. The concerts were presented by various groups of the school and finally the results of different grades’ terminal exams were announced. The school closed.

Happiness had been deprived of me. From that very night loneliness came on me. I had been enjoying for the past 2 weeks. Hunting, looking at the school girls, looking and studying their differing characters and their responses. Besides all I had danced with a lot of them for the past 3 joyous ball dances and all these contributed to my unhappiness. Misery started right from the time I opened my eyes the following day. Playing records couldn’t amuse me neither hunting. A natural depression had crept into my mind. I had no power, completely discouraged. I wondered what my real holidays would become of while seated on the arm chair. I was feeling sleepy. The word natural depression seemed to prick my ears. My brother-in-law asked what was wrong with me. I said nothing.

Sophia, Misozi, Sarah all these girls had left yesterday. People whom I had enjoyed to see, people whom I had liked to speak to, people whom I was happy to study their differing characters, they had made my stay a bright and comfortable one. I remembered when Sophia failed to approach and meet me she turned and went through the village to another short path. Misozi was always ready to dance without any doubts. She just gave herself up. Sarah and Sophia were the first two girls I had learnt on how to dance ballroom with. I wasn’t going to see their faces anymore. Probably Misozi who was the nearest to me. The more I thought of them the more my heart became heavy.

To cheer up myself, I took the bird air gun for hunting but that couldn’t do either.

My thoughts went deeper into the holidays. My friend Isaac was going to Ndola, Samson to Lusaka, Philip to Luanshya. With whom will I stay? That was the main worry adding to the ones which were already there.

I almost thought all night and finally made a conclusion to go to Lusaka again for my holidays.

There were a number of things which father was going to consider. I had gone there in August, he didn’t actually allow me, but with the help of brother-in-law I had gone to Lusaka. Mother was away to Lumezi and therefore father wouldn’t make immense decisions like this one on his own. Otherwise he would prove to have been wrong later.

I was in despair already, before I could go to ask for transport money. I am a boy I thought to myself I should have a try first. I went to his home, and found he wasn’t there. I left a letter demanding for permission and transport money.

The following day I went and collected K10 for transport. I was filled with joy and relief. Brother-in-law and sister wondered what had happened to father to allow me to go to Lusaka again.

————–End of Book One——————-