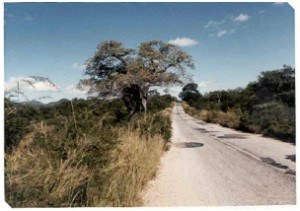

My family and I in 1959 lived at Chasela Primary School in the Luangwa Valley among the Bisa people in the Eastern Province of Zambia in Southern Africa. I was five years old. My father was a teacher during British colonialism in the then Northern Rhodesia. We lived in a small 3 room redbrick house with grass roofing. At the time the Luangwa Valley had numerous wild animals roaming night and day like Africa had been probably for thousands of years. Lions, zebras, large herds of buffaloes, impalas, hyenas, monkeys, leopards, birds, and elephants were everywhere night and day and around our house. Humans and deadly encounters with wild animals were as common as traffic accidents are today in our time.

One day, my dad went on a business trip to Fort Jameson (now Chipata) riding his bike through sixty miles or ninety-six Kms. of dangerous desolate wilderness in the Luangwa Valley. At that time there were few people and villages. My mother asked me to leave my bedroom and instead to sleep in my dad’s bed next to my mother’s since we were by ourselves that night. It was 1900 hrs. 7:00 pm and the yellow paraffin lamp was dimly burning and flickering on mom’s small bedside table. My mom had just finished giving a bath to my seven-month-old baby sister, Ester. Ester was whining and fussing with mom bugging her.

“Mama nipeni baseline!!” She whined.

My baby sister wanted the “baseline” bottle to apply the Vaseline on herself again. My mom was saying “No! will you please go to sleep!” When all of a sudden:

“Graaaaaaaaargh!!!!!!” One lion roared with the deepest bellow literally five feet or two meters outside our rickety wooden bedroom door and window.

“Graaaaaaaaaaargh!!!!” The second lion roared in response. Our whole small three room red brick house shook and vibrated.

My mother hastily blew out the kerosene lamp. My little sister tried to dive under mom to hide. I froze. Deep fear hit the pit of my little stomach. I was so scared I could not move to hide under the covers. My little heart may have stopped and I could not breath. The plates, dishes, pots, and pans rattled on the kitchen shelves as some loudly crashed to the bare cement floor in the kitchen. Some rats fell with a thud from the grass roof. The two lions continued to roar in tandem.

There was loud commotion in the nearby Chibande large village of five hundred as playing children screamed and fled in terror. Mothers desperately yelled calling their children by name to “please run home!!!.” Most kids ran into the nearest house for cover for that night as there was no time to run to their parents’ house.

When I opened my eyes in the morning, it was very quiet and it was almost 9:00 hours. This was very unusual as we always woke up early in the morning at 6:00 hours.

First, my mother said a brief prayer thanking God for having saved our lives that night. She then gingerly opened our small wooden bedroom window and carefully peeked outside to make sure the lions were not waiting anywhere outside. That’s when we came out of the house. The bedroom door that led to the outside just left of where the lions had roared was a small thin wooden door. The lion could have effortlessly just put its paw on the small door, and it would have been inside our bedroom. Later that day, my mom told me that a few seconds prior to the lion’s first roar a few feet from our bedroom door, she had heard strange sounds. “Pomp!!” “Pomp!!!” Pomp!!!” We found out later on that those were sounds of the lions wagging their tails hitting both sides of their stomachs as they quietly approached our house under the mango trees. When we looked at the footmarks, the pride had been about ten to fifteen lions. I often wonder what scares children today compared to those older times.